Was it an accident, or intention, that caused Winthrop Packard to title this volume using his own initials for inspiration (just as he had with Woodland Paths the year before)? How much is Packard playing with the reader in these essays? Does he seek to evoke a magical element in nature as a rhetorical device pointing to the wonders of the everyday? Or does he genuinely believe in it? Is his “science skepticism” real, or merely feigned? Who is laughing at whom? I honestly don’t know for sure. All I can do is present what I have read and let readers decide for themselves.

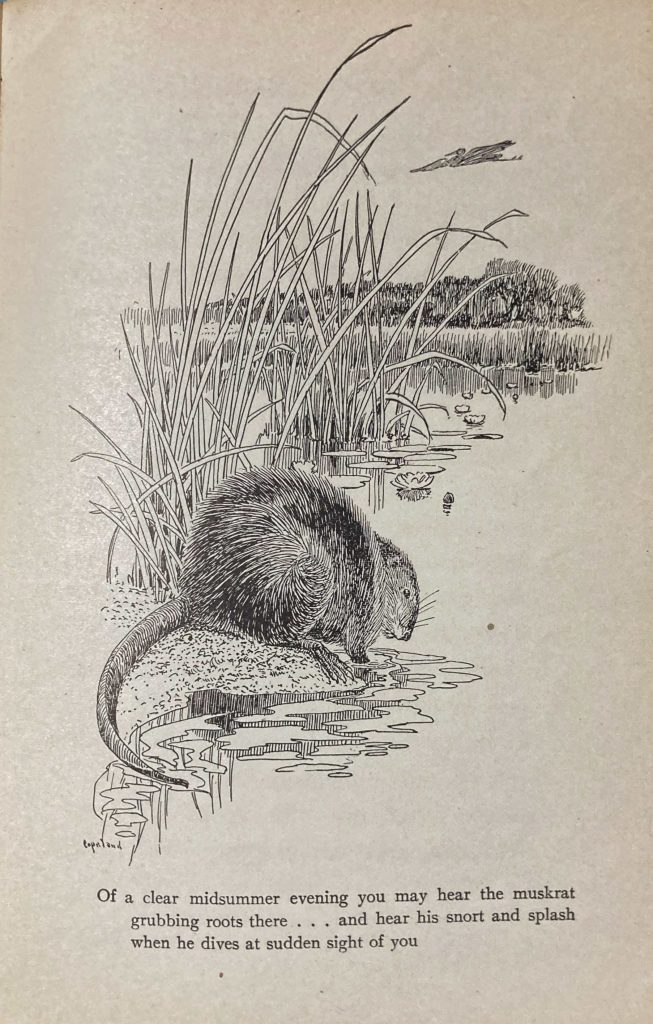

Horace Lunt opened his Short Cuts and By-Paths by noting that “not much of scientific value has been demonstrated in these pages” — then went on to describe with scientific exactitude the nature of lichens, mosses, and invertebrates of the seashore. If his work is “not much of scientific value”, I am not sure what to make of Packard’s prose. His descriptions are pleasant (he has a keen eye for colors) and he has quite a bit of botanical knowledge. He demonstrates basic awareness of common butterflies and their behaviors. And when writing about Ponkapoag Pond in Blue Hills State Reservation south of Boston, he describes the process by which a pond becomes a bog and then a marsh and eventually a field. Yet when he shares the ways of the witch hazel shrub in his chapter “Brook Magic”, he veers away from science into folklore, where he seems more comfortable:

Pluck one of the [witch-hazel] nuts of a midsummer evening and look it in the face. Note the little shrewd pig eyes of the witch ingrown in it, the funny shrewish tip-tilted nose, the puffy cheeks and eyelids. See that slender horn in the forehead, the sure mark of the witch. No wonder that it has the name witch-hazel with such ways and such faces growing all over it at a time when most other trees and shrubs have but finished blossoming. But if you want further proof that the shrub harbors witches than you need but to examine its oval, wavy-toothed leaves just at this time of the year and see the little conical red witch-caps hung on them. There need be but little doubt that, sitting under it at midnight of a full moon, you may see the witch faces detach themselves from the limbs, put on these red caps and sail off across the great yellow disk. That such things are not seen oftener is that people are dull and go to bed instead of sitting out under the witch-hazel at midnight of a full moon.

To be sure there are scientific men, grey-bearded entomologists, who will tell us that these little red caps are galls, the rearing-place of plant aphids, caused by the laying of the mother insect’s egg within the tissue of the leaf, but one might as well believe that the witches hang their hats on the witch-hazel over night as to believe that the laying of a minute egg in the tissue of a leaf could cause the plant to grow a witch hat.

No doubt these same wise men would explain to you that it is not possible to become invisible by sprinkling fern seed on your head during the dark of the moon and saying the right words, but did one of them ever try it?

It is appropriate that the witch-hazel should shade the portals through which the brook enters the glen at the foot of the pasture, for the path here enters you into a world of witchery where the glamour of the place will hold you long of a summer afternoon.

Winthrop Packard, what are you saying here? My first thought was that he was alluding to the seemingly magical facets of scientific explanations, but I wonder at that. There is another possibility, namely, that he longs to inhabit a world where magic still exists — evoking Donovan more than half a century later, “Still I hear facts, figures, and logic; fain would I hear lore, legend, and magic.” Is the scientist in Packard’s mind a wise interpreter of nature, or a bogeyman dispelling enchanting fancies in the light of empirical knowledge?

Packard is not quite done arguing with science, however serious or whimsical his remarks might be. In a later essay on “Some Butterfly Friends,” he speaks more directly about scientific knowledge. In the passage below, he engages in a flight of fancy before coming back to earth with a more viable explanation of pollination:

I do not know what the clethra which gleams in white in the dusk should need anything more than its own white beautfy to call the moth to its wooing. Perhaps it does not need more. Perhaps all this fine fragrance isbut the overflow of its soul’s delight at being young and chastely beautiful, and trembling in the ultra violet darkness on that delicious verge of life that waits the wooer. I half fancy that it is true of all perfume of flowers, that it is less a call to butterfly or bee to come to their winning than it is a radiation of delight from their own pure hearts at the dawning of the full joy of living. I am not always willing to take the word of the scientific investigator on these points as final. The scientists of the not very remote past have known so much that is not so!

It is possible that, just as a hunting dog picks up a scent that is strong in his nostrils and has no power in ours, so the flowers that we call scentless send out an odor too faintly fine for our senses, yet one that the antennae of moth or bee may entangle as it passes and hold for a certain clue. Perhaps the scents that are only faint to us carry far for the butterfly, but if so, and if flower perfumes are made only for the calling of insects, why need they be made so intoxicating to the human senses?

And there is a third possibility — that it is all just a game, these evocations of magic in pastures and streams, this poking at scientists. Just like the naming of his books — Wild Pastures, Woodland Paths. Still, at least his words, images, and imaginings make for fairly pleasant if somewhat insipid reading — an acceptable diversion for a long sultry summer afternoon. Oh — and the book cover is pretty, too.

Winthrop Packard is decidedly obscure, having thus far avoided an entry in Wikipedia. He lived from 1862 until 1943, and he wrote quite a few books in the “nature” genre. One source notes that he was also a lyricist and composer. Thanks to a newspaper obituary, I also know that Packard was secretary-treasurer of the Massachusetts Audobon Society and that he established and financed the Society’s first bird sanctuary (Moose Hill) in Sharon, Massachusetts in 1916. He graduated from MIT in 1885 and worked as a chemist in Boston. He somehow ended up in the newspaper business, becoming editor of the Canton Journal in 1894 and then switching to National Magazine, Youth’s Companion, and finally the Transcript. He was a member of an expedition to Alaska and Siberia in 1900. He married Alice Petrie and had four sons.

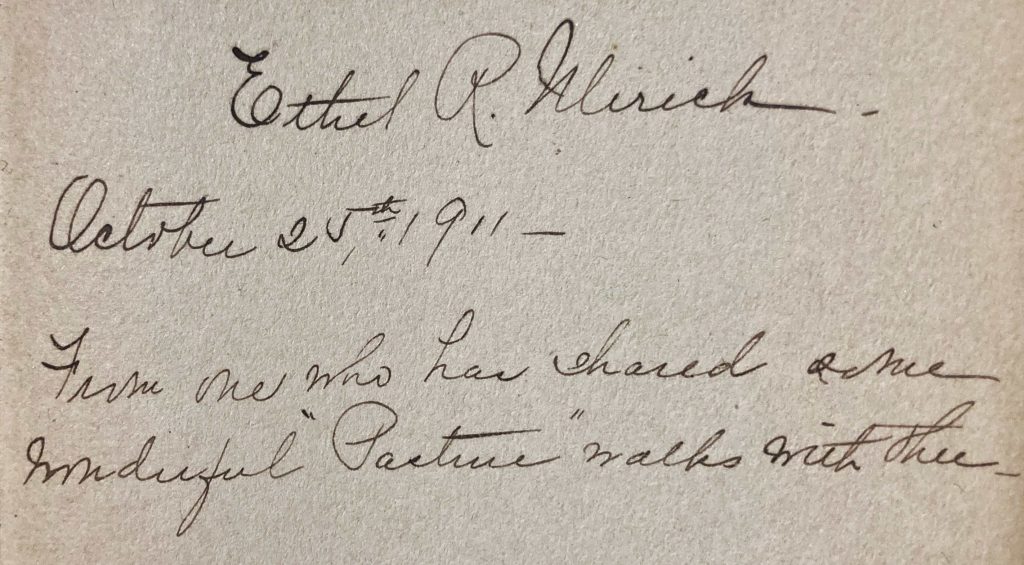

My copy of Wild Pastures is in superb shape; the cover looks practically new. It was signed by a previous owner, Ethel R. Ulrick (Ulrich?) on October 25th, 1911; she appears to have accomplished an even greater level of Internet obscurity than Packard.