“In the afternoon a strong, cold wind blows from the west. I cross the river and the peninsula beyond to the ocean’s beach. Before me the Atlantic stretches eastward, blue and unbroken to the shores of Africa. The wind blows off shore, and except for the sight and roar of the surf I would not know the ea was there. No odor of salt water, no sign of seaweed greets me. The beach is a hard, unbroken mass of reddish yellow sand, with only here and there the valve of a sea shell or the body of a giant sea squid to break its monotony. Not a pebble, not a sign of fish, not a rock for the waves to dash upon ; how different from the beach of the same ocean along New England’s rock-bound coast! A solitary steamer of small size, southward bound, about half a mile from shore, is the only vessel in sight. After an hour the whole scene becomes monotonous in the extreme and, on account of the sharp wind which catches up and carries outward clouds of sand from the inner edge of the beach, very disagreeable.”

Told by his doctor that he should take a vacation in the south to recover from “nervous prostration”, Willis Blatchley (1859-1940) journeyed south by train to Ormond by the Sea (now part of the City of Ormond Beach) in March of 1899. He chronicles his time in Florida (and his midlife crisis — see my previous post on this book) in A Nature Wooing at Ormond by the Sea. (Yes, that is one of the oddest titles of a natural history book I have encountered in my research thus far.). But for those picturing a Florida vacation as days on the beach and nights in fine restaurants and resort hotels, Blatchley managed nearly completely to avoid it all. One of his rare beach outings, reported above, was a disaster. He visited a different beach later in his vacation but was most taken with the wreck of a ship that had recently washed ashore, and spent very little time observing the waves or even the seabirds.

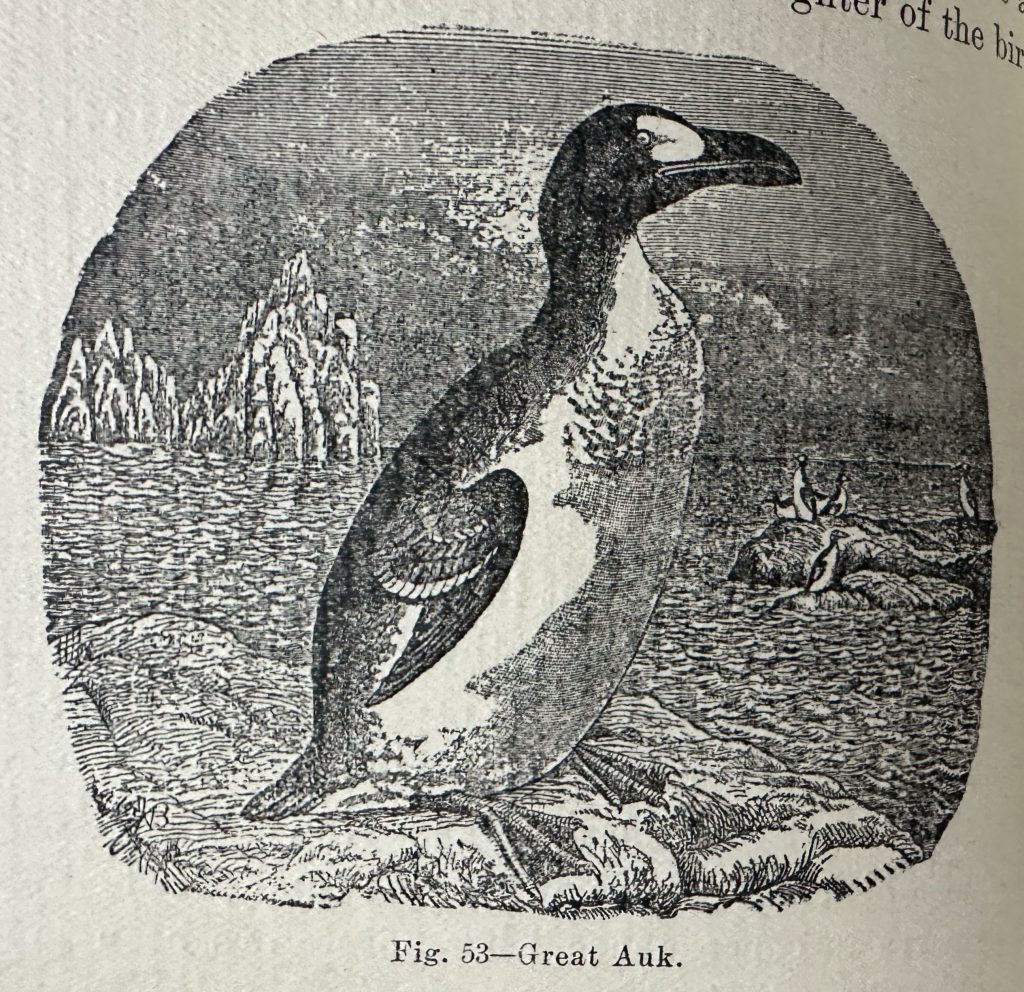

Instead, for Blatchley, vacation was an opportunity to continue the life he loved in Indiana, but in a warmer, more humid, more biodiverse setting: observe wildlife, particularly small organisms. Mostly, he turned over many logs and reported on what he saw (making A Nature Wooing a logbook of sorts). He did a bit of botanizing, a modicum of birdwatching, and a fair bit of observing of critters in shells (or just the empty shells). He spent a few days poking about in a local shell midden, Ormond Mound (now known as the Timucua Indian Burial Mound). And for all his casual rambling, Blatchley even managed to make important discoveries for science and archaeology. First, he observed a belly-up horseshoe crab right itself (something renowned naturalist Thomas Say had claimed was not possible). Then, while excavating the lowermost level of Ormond Mound, he discovered the humerus bone of a Great Auk! The discovery was reported in the newspapers in the spring of 1902; Prof. C. H. Hitchcock, of Dartmouth College, was in Ormond at the time, and immediately began an excavation of his own, unearthing a second Great Auk bone — another left humerus, indicating that at least two birds had been caught (and presumably eaten) there. According to the Florida Museum, these bones date back only about a thousand years, indicating that Great Auks likely wintered along the Atlantic coast of Florida during the Little Ice Age. Presumably, they migrated seasonally from their northern nesting grounds. That would have been quite a journey, given that they had lost the ability to fly and would have had to swim the entire way.

I admit to being astonished at how Great Auks were present in Florida just a few hundred years before they went extinct. According to Blatchley, another extinct bird may still have been living in the northern part of Florida in 1899, too. According to a couple of local fieldworkers, Ivory-Billed Woodpeckers still inhabited heavily timbered hammocks (uplands) in the region, while the Carolina Parakeet had been seen around Ormond as recently as 1887. Both, Blatchley noted, had once been common in Indiana but had long since vanished from the state.

Where Blatchley’s work particularly shines (apart from the midlife crisis angle I explored in a previous post) is in his thorough documentation of the biodiversity of a corner of Florida that has since succumbed to dramatic sprawl. At the time of Blatchley’s visit in 1899, Ormond had only 600 residents; now, greater Ormond Beach is home to over 43,000 people. Some of what Blatchley saw has been preserved, fortunately. The “old Spanish chimneys” that were a popular tourist destination in 1899 have been preserved (and partially restored) as Dummett Sugar Mill Ruins (although Blatchley was much mistaken about their age — supposedly over two hundred years old at the time and of Spanish origin, they had actually been constructed by a British entrepreneur only 75 years earlier). Part of the Tomoka River that Blatchley explored also remains relatively untouched, in Tomoka State Park. In addition to detailed descriptions and drawings of many of his animal finds (especially insects), Blatchley’s book also includes a list of all the insects he identified in the Ormond area. It would be a fascinating research project (M.S., anyone) to return to the region and see how many of them can still be found there today.

Finally, a promised few words of biography. Alas, for all the books he wrote and travels he undertook, he is little known today. There is a nature club in Indiana that bears his name, but there is no direct connection beyond the club founder thinking highly of Blatchley. He moved from Connecticut to Indiana at the age of one and never left the state. For many years he headed the Science Department at Terre Haute High School. He also served as State Geologist for 16 years. He married Clara Fordyce (or Fordice?) in 1882, and they had two sons. After a couple of visits to Florida (including the one chronicled here), he purchased land in Dunedin, near Tampa, and had a winter residence built. He visited there regularly, and one of his nature books chronicles his nature observations from a tree on his property. His journeys took him to Mexico, Alaska, and South America (the last trip being the topic of his final published work). He died in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1940 at the age of 80. He is most famous today for his contributions to entomology. None of his books was ever reprinted, with the exception of a small commemorative run of his book set in Dunedin, My Nature Nook, courtesy of the Dunedin Historical Society.