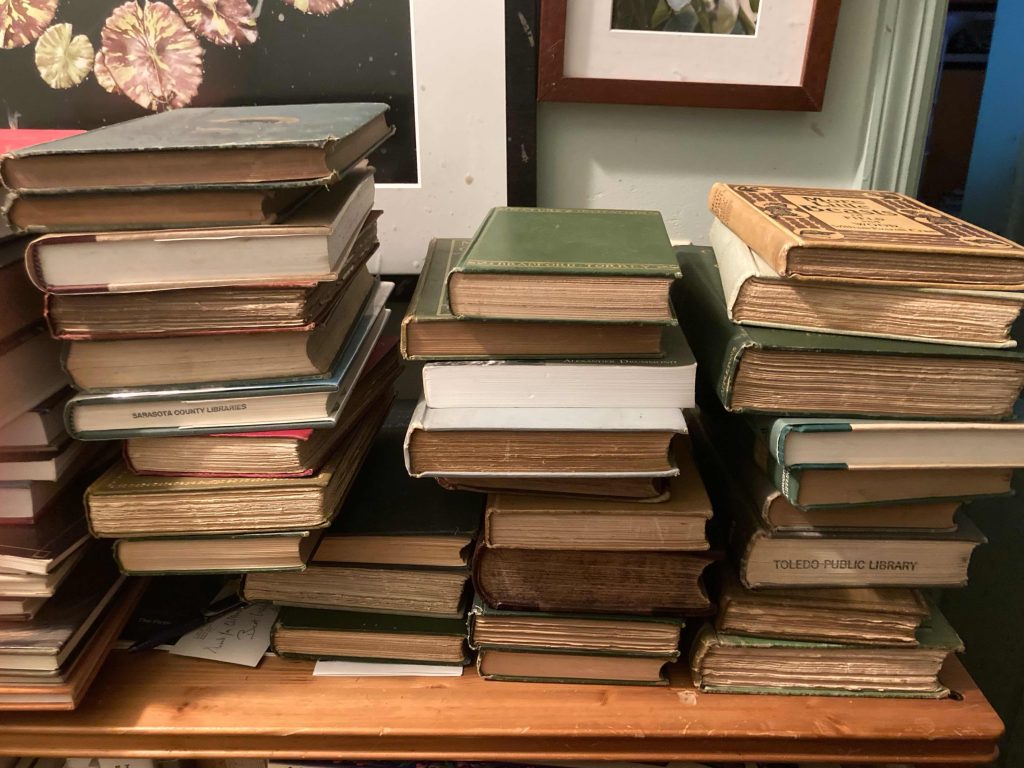

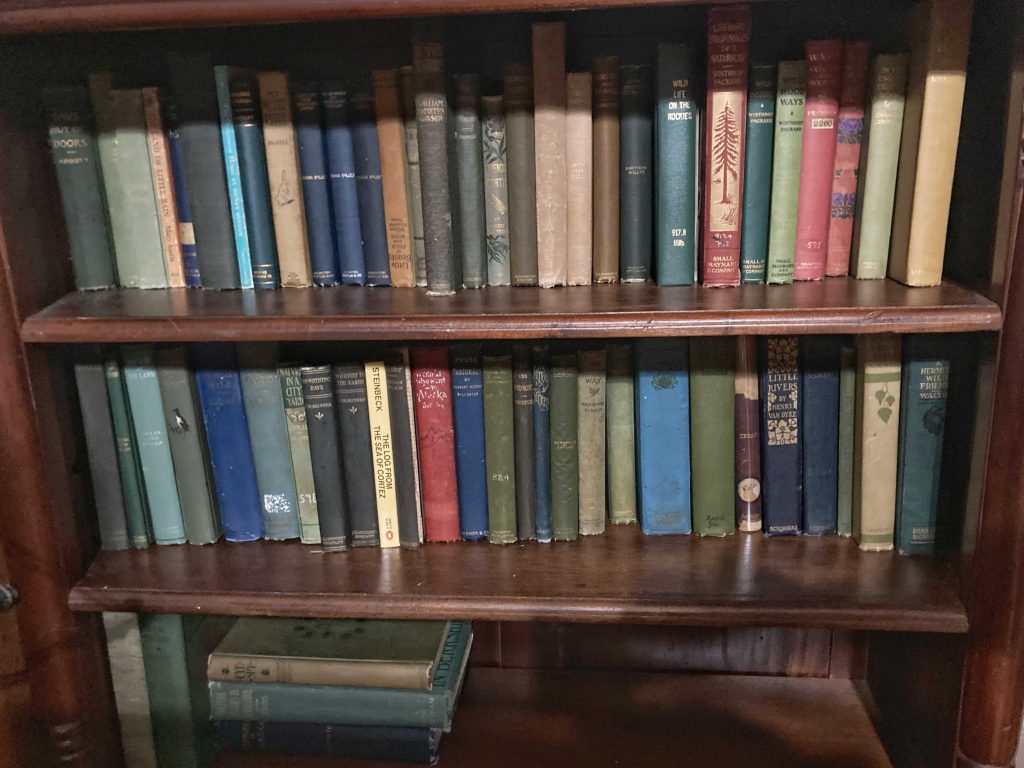

OK, I have a Book Problem. I own it. I have books everywhere, in a dozen bookcases and stacked in piles atop the bookcases. And lately, a lot of those books have been of the antiquarian ilk. For those of you wondering how I finance this blog, it is a labor of love — and debt. I do not want to run the numbers, but I am confident I have spent something north of $3000 on obtaining original (or near-original) copies of perhaps 150 “nature” books, from the 1850s into the 1930s. My wife has been, for the most part, looking aside while I have been indulging this habit, though she has flinched a couple of times at purchases above $50 for a single highly desired volume. (I think $70 is my record unless you count the complete set of John Burroughs.) There are a few books I will simply do without. An original copy of Days Afield on Staten Island (1892) starts at $150, for instance — though I did manage to buy a paperback reproduction for under $5. Lately, she has finally called a halt to my acquisitions, though I had already decided I have reached a state of saturation. I now own a large percentage of the books of the more prolific authors of the time — including the 23-book Collected Works of John Burroughs. I have enough to be truly humbled by it all.

You are probably wondering why at this point. Not why I am reading the books, I hope — I feel like I have discovered a treasure-trove of writers the world has forgotten, from a golden age of nature writing nobody talks about anymore. I am thrilled at the prospect of creating an anthology to celebrate them all (or at least the ones worthy of celebrating). But why the original editions, when I could read nearly every book online for free, or buy on Kindle or in paperback from less than half the price of the original?

My answer is that reading, to me, is a richly sensorial experience. I blame my friend Alan Craig for that. He is not really responsible, even indirectly. But his grandfather, who was largely responsible, has passed on, and his father, who probably shares a bit of the blame, I have not spoken with for years and would not wish to offend by dint of blame, so I will blame Alan in his stead. You see, when I was in about 5th grade, I would roam through my neighborhood, knocking on people’s doors and visiting with them. Nobody told me not to do that, and I honestly enjoyed conversations with older folks (ones about my age now, I expect). The Craigs has a charming rambling home that included a den, and that den was lined with bookshelves, and in the bookshelves were books, and one of them was in a red slipcase and had a huge spine decorated with runes. Jeff Craig had given the book to his father. I knew zero about the book or its author (The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien). But based on the cover alone, I was fascinated. I was permitted to take the book home to read. I remember the weight of the book in my lap, the way the map in the back unfolded to reveal Middle Earth, the smell of the book, and the feeling of sliding it out of its slipcase. That is when I truly discovered reading as a vehicle for visiting other worlds. And that is when I experienced reading as embodied, sensorial. I will assert to this day that a set of three mass-market paperbacks of The Lord of the Rings is not the same book as the one I read. I know, because I tried reading it in paperback copies years later.

What does this have to do with my current project? Everything. There is a magical quality to holding an old book in my hands, turning the pages, viewing hundred-year-old photographs, viewing signatures of past owners whose grandchildren are dead and buried by now. My most recent venture, Star Papers, is a first edition of the work, from 1855. With some luck, I will live to see its 200th birthday. The cover is dark and rather depressing — it would fit in well in a Victorian parlor at a viewing. The paper is robust — likely a thick cotton rag. The printing is letterpress — I can feel each letter on the page.

What is even better, the author, Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887) understands me well. We are kindred spirits in our dedication to bibliophilia. His essay on “Book-Stores, Books” speaks directly to my book pursuits, though written back before the Civil War. My next post will visit in great depth with his book as a whole, especially in regard to his sentiments on nature. For this post, though, I cannot help but share his essay on the purchasing of books in its entirety. If it describes your plight, reader, know that you are not alone.

Nothing marks the increasing wealth of our times and the growth of the public mind toward refinement, more than the demand for books. Within ten years the sale of common books has increased probably two hundred per cent, and it is daily increasing. But the sale of expensive works, and of library-editions of standard authors in costly bindings, is yet more noticeable. Ten years ago, such a display of magnificent works as is to be found at the Appletons’ would have been a precursor of bankruptcy. There was no demand for them. A few dozen, in one little show-case, was the prudent whole. Now, one whole side of an immense store is not only filled with most admirably bound library-books, but from some inexhaustible source the void continually made in the shelves is at once refilled. A reserve of heroic books supply the places of those that fall. Alas! Where is human nature so weak as in a book-store! Speak of the appetite for drink; or of a bonvivant’s relish for a dinner! What are these mere animal throes and ragings compared with those fantasies of taste, of those yearnings of the imagination, of those insatiable appetites of intellect, which bewilder a student in a great bookseller’s temptation-hall?

How easily one may distinguish a genuine lover of books from the worldly man! With what subdued and yet glowing enthusiasm does he gaze upon the costly front of a thousand embattled volumes! How gently he draws them down, as if they were little children; how tenderly he handles them! He peers at the title-page, at the text, or the notes, with the nicety of a bird examining a flower. He studies the binding: the leather, — Russia, English calf, morocco; the lettering, the gilding, the edging, the hinge of the cover! He opens it, and shuts it, he holds it off, and brings it nigh. It suffuses his whole body with book-magnetism. He walks up and down, in a maze, at the mysterious allotments of Providence that gives so much money to men who spend it upon their appetites, and so little to men who would spend it in benevolence, or upon their refined tastes! It is astonishing, too, how one’s necessities multiply in the presence of the supply. One never knows how many things it is impossible to do without till he goes to Windle’s or Smith’s house-furnishing stores. One is surprised to perceive, at some bazaar, or fancy and variety store, how many conveniences he needs. He is satisfied that his life must have been utterly inconvenient aforetime. And thus, too, one is inwardly convicted, at Appleton’s, of having lived for years without books which he is now satisfied that one can not live without.

Then, too, the subtle process by which the man convinces himself that he can afford to buy. No subtle manager or broker ever saw through a maze of financial embarrassments half so quick as a poor book-buyer sees his way clear to pay for what he must have. He promises with himself marvels of retrenchment; he will eat less, or less costly viands, that he may buy more food for the mind. He will take an extra patch, and go on with his raiment another year, and buy books instead of coats. Yea, he will write books, that he may buy books. He will lecture, teach, trade; he will do any honest thing for money to buy books! The appetite is insatiable. Feeding does not satisfy it. It rages by the fuel which is put upon it. As a hungry man eats first, and pays afterward, so the book-buyer purchases, and then works at the debt afterward. This paying is rather medicinal. It cures for a time. But a relapse takes place. The same longing, the same promises of self-denial. He promises himself to put spurs on both heels of his industry; and then, besides all this, he will somehow get along when the time for payment comes! Ah! this Somehow! That word is as big as a whole world, and is stuffed with all the vagaries and fantasies that Fancy ever bred upon Hope. And yet, is there not some comfort in buying books, to be paid for? We have heard of a sot, who wished his neck as long as the worm of a still, that he might so much the longer enjoy the flavor of the draught! Thus, it is a prolonged excitement of purchase, if you feel for six months in a slight doubt whether the book is honestly your own or not. Had you paid down, that would have been the end of it. There would have been no affectionate and beseeching look of your books at you, every time you saw them, saying, as plain as a book’s eyes can say, “Do not let me be taken from you.”

Moreover, buying books before you can pay for them, promotes caution. You do not feel quite at liberty to take them home. You are married. Your wife keeps an account-book. She knows to a penny what you can and what you can not afford. She has no “speculation” in her eyes. Plain figures make desperate work with airy “somehows.” It is a matter of no small skill and experience to get your books home, and into their proper places, undiscovered. Perhaps the blundering Express brings them to the door just at evening. ” What is it, my dear?” she says to you. “Oh nothing — a few books that I can not do without.” That smile! A true housewife that loves her husband, can smile a whole arithmetic at him in one look! Of course she insists, in the kindest way, in sympathizing with you in your literary acquisition. She cuts the strings of the bundle, (and of your heart) and out comes the whole story. You have bought a complete set of costly English books, full bound in calf, extra gilt! You are caught, and feel very much as if bound in calf yourself, and admirably lettered.

Now, this must not happen frequently. The books must be smuggled home. Let them be sent to some near place. Then, when your wife has a headache, or is out making a call, or has lain down, run the books across the frontier and threshold, hastily undo them, stop only for one loving glance as you put them away in the closet, or behind other books on the shelf, or on the topmost shelf. Clear away the twine and wrapping-paper, and every suspicious circumstance. Be very careful not to be too kind. That often brings on detection. Only the other day we heard it said, somewhere, “Why, how good you have been, lately. I am really afraid that you have been carrying on mischief secretly.” Our heart smote us. It was a fact. That very day we had bought a few books which “we could not do without.” After a while, you can bring out one volume, accidentally, and leave it on the table.” Why, my dear, what a beautiful book! Where did you borrow it?” You glance over the newspaper, with the quietest tone you can command: “That! oh! that is mine. Have you not seen it before? It has been in the house these two months;” and you rush on with anecdote and incident, and point out the binding, and that peculiar trick of gilding, and every thing else you can think of; but it all will not do; you can not rub out that roguish, arithmetical smile. People may talk about the equality of the sexes! They are not equal. The silent smile of a sensible, loving woman, will vanquish ten men. Of course you repent, and in time form a habit of repenting.

Another method which will be found peculiarly effective, is, to make a present of some fine work, to your wife. Of course, whether she or you have the name of buying it, it will go into your collection and be yours to all intents and purposes. But, it stops remark in the presentation. A wife could not reprove you for so kindly thinking of her. No matter what she suspects, she will say nothing. And then if there are three or four more works, which have come home with the gift-book — they will pass through the favor of the other.

These are pleasures denied to wealth and old bachelors. Indeed, one cannot imagine the peculiar pleasure of buying books, if one is rich and stupid. There must be some pleasure, or so many would not do it. But the full flavor, the whole relish of delight only comes to those who are so poor that they must engineer for every book. They set down before them, and besiege them. They are captured. Each book has a secret history of ways and means. It reminds you of subtle devices by which you insured and made it yours, in spite of poverty!

The smell of used bookstores, or rather, the basements of used books stores (never having very much money to spend, many of my purchases were acquired from basements) always remind me of rainy Sunday afternoons. When I entered into these domains and wandered through the stacks, or paused, sitting on the floor with one or two books open in my lap, tempting me, it was almost like a rite. Perhaps a rite of passage. Anyway, the smell of rainy Sunday afternoons always reminds me of these rites [of passage] between being the child who was content with the books in my own collection (and there were not that many) and the hundreds of books that were not mine. These books––the ones that were not mine––were set in bookshelves or cabinets. There were my parents’ books. But leaving childhood, I left the familiarity of their collections and the books with familiar titles. In those trips to the used bookstore, I encountered myself as an adult, or almost an adult, for the first time. I had the freedom to choose, to open, to investigate. Obviously, Clifford, you have had similar experiences. This blog is another passage. or, should we say, “passageway”. grazie mille.