…A few more similar expositions of the beautiful mysteries of the common flowers which we meet every day in our walks, and which we claim to “know” so well, may serve to add something to the interest of our strolls afield. It is scarcely fair to assert that familiarity can breed contempt in our relations to so lovely an object as a flower, but certain it is that this everyday contact or association, especially with the wild things of the wood, meadow, and wayside, is conducive to an apathy which dulls our sense to their actual attributes of beauty. Many of these commonplace familiars of the copse and thicket and field are indeed like voices in the wilderness to most of us. We forget that the “weed” of one country often becomes a horticultural prize in another, even as the mullein, for which it is hard for the average American to get up any enthusiasm, and which is tolerated with us only in a worthless sheep pasture, flourishes in distinction in many an English or Continental garden as the “American velvet plant.”

Try as I may, I cannot shake the parallels from my mind. Every time I bring William Hamilton Gibson (1850-1896) into my thoughts, inevitably I also think of James Abram Garfield (1831-1881), 20th President of the United States. Both have three names (though Garfield’s middle name is usually abbreviated to A.); both have last names of two syllables, beginning with G; both were of roughly the same era; both were quite gifted — Garfield in politics, Gibson in art and writing; both sported similar beards; and both died tragically at a young age (well, younger than I am, a least). James A. Garfield fell to an assassin’s bullet just a few months into his Presidency; William H. Gibson died of a stroke from overwork just a few months before Eye Spy was published. Of the two, I think Gibson was likely the more light-hearted and playful; Garfield looks fairly serious in this photo. I greatly admire Garfield, but since this is a nature blog (and since Candace Millard already crafted a fabulous biography of him), I will focus solely on Gibson in this post, despite my innate need to associate them somehow.

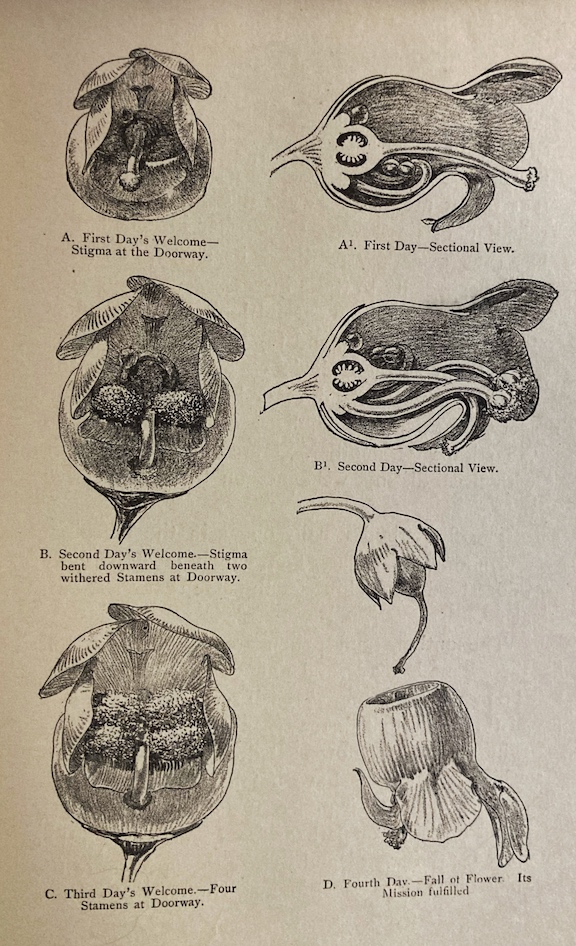

Gibson was a gifted artist who closely observed the world around him — particularly what lay at his feet, in the form of both flowers and the insects associated with them. Employing the two skills in tandem, Gibson reveals in Eye Spy many mysteries pertaining to everyday nature in rural New England, where his studio was situated. “The beauty of the commonplace often requires the aid of the artist as its interpreter,” he remarks in an early essay in this volume. He then proceeds to share with readers, using careful drawings, how the lowly figwort (“a tall, spindling weed”) orchestrates visits by the tiny wasp that pollinates it. He reveals how “these queer little homely flowers” function as “mere devices — first, to insure the visit of an insect, and second, to make that insect the bearer of the pollen from one blossom to the stigma of another.”

I will not bother with the complexities of the process here, but you can read all about this sequence of images in Gibson’s essay, “A Homely Weed”.

One particularly noteworthy feature of this book is that, in keeping with Darwin’s evolutionary theory, Gibson examines flowers and insects together, in light of the “‘new botany’, which recognizes the insect as an important affinity of the flower–the key to its various puzzling features of color, form, and fragrance…” Gibson, though, goes beyond Darwin to imbue these relationships with spiritual significance, reflecting “the conscious intention of the flower as an embodiment of a divine companion to an insect.” Remarking on how botany has been transformed by Darwin’s work, Gibson exclaims in “Riddles in Flowers”: “What puzzles to the mere botanist! for it is because these eminent scholars were mere botanists—students and chroniclers of the structural facts of flowers—that this revelation of the truth about these blossom features was withheld from them. It was not until they had become philosophers and true seers, not until they sought the divine significance, the reason, which lay behind or beneath these facts, that the flowers disclosed their mysteries to them.”

Gibson’s volume (culled largely from previously-published essays) is a book full of magic and mystery, equally inviting to older children and adults. Some chapters focus on the mysteries of pollination, others on predation and parasitism. In one essay, a “mischief-making midge” lays an egg inside a stem or leaf, producing a gall. Three of Gibson’s accounts have a dimension of tragedy — parasitic wasps laying eggs inside caterpillars, cicadas, and grasshoppers, leading to their slow, inevitable death. Others exude joy and delight; in “The Dandelion Burglar”, a dandelion falls victim, not to an insect, but to a redstart thief — a “tiny, black bird with a rosy band in his tail” who steals the developing seeds of a recently-bloomed dandelion to line its nest. Yet other essays reveal to readers how to take spore prints from a mushroom, and how to increase the likelihood of finding multiple four-leaf clovers. My favorite essay in the book reports on the engineering feats of spiders, building bridges very much in keeping with the feats of human engineering. It is entitled “The Spider’s Span”, and I include it in its entirety below.

Observers who witnessed from day to day the construction of the great Brooklyn Bridge were often heard to remark, as they looked up with awe from the ferryboats beneath at the workmen suspended everywhere among the net-work of cables, “Those men look just like spiders in a web.” The comparison seemed irresistible, and the writer heard it expressed many times. But how few who gave utterance to the sentiment realized the full significance of the “spider” allusion, or for a moment reflected that the span itself was, in many particulars of its construction, but a parallel of an engineering feat of which the spider was the earliest discoverer. Yet among all the distinguished names engraved upon the memorial tablet upon the stone bridge-tower the spider gets no credit.

Day after day and week after week we might have seen, travelling back and forth against the sky, a wheel-shaped messenger reeling off its tiny wire. Night and day it was busy, each trip adding one more strand to the growing cable which was to support the great substructure below. And what was this travelling wheel called? “ The carrier,” or “traveller,” if I remember rightly. Why this obviously intentional slight and discourtesy when every field and wood and copse in the country—indeed, on the globe—showed its living example, and bore its myriadfold witness that the “spider” was the only legitimate and proper designation?

In the other most notable suspension-bridge, at Niagara, the time-honored methods of the spider were further and conspicuously recognized, but here again without any courteous engraven acknowledgment on the tablet of fame, so far as I have learned.

A kite was flown from the American shore, and reeled out so as to fall upon the Canadian side, and this initial strand was drawn across, and subsequently strengthened by the travelling reel. The ends of the added wires were firmly secured at their anchorage, and the completed cable at length re-enforced by guy-ropes.

What is the method of our spider? Ages before the advent of the human engineer he followed the same tactics which we now see him performing in every meadow, or even at our window-sill, or on the bouquet upon our table, linking flower with flower, window-sill with garden fence, bush with bush, tree with tree, with his glistening suspension-bridge spanning the stream, river, and meadow. This wiry thread that tightens across our face as we ride in our carriage, and leaves its tingling “snap” upon our nose, what is this but the model suspension cable of Arachne strengthened a hundredfold by the spider which has travelled back and forth over its course for hours perhaps, each trip leaving a fresh strand, one extremity being anchored on yonder oak in the meadow and the other on the church steeple? Such a cable twenty feet in length is a common challenge in our walks in the open wood road, even making a perceptible motion among the leaves and bending twigs on either side ere it yields to our advance. And to the walker who cares to investigate, a silken bridge a hundred feet in length is not a very exceptional find.

This bridge-building is not confined to any particular month or season, nor to any one species of spider. The autumn will afford us the best opportunity for observation. At that season the spider-egg tufts are turning out their baby spiders by the millions, each a perfect grown spider in miniature, and apparently as skilled at birth in the peculiar arts of its kind as its parents were in their ripe old age. Here is a troop of them upon this drooping branch of wild grape by the river brink. Its leaves are glistening in the loose, rambling tangle which marks their wanderings. They are evidently not satisfied with their present surroundings, and would seem desirous of getting as far as possible from the neighborhood of their cradle and swaddling-clothes. They are the most independent and self-reliant babies on record. They ask advice from no one—indeed their mother died a year ago, perhaps—but each determines to leave his brothers and sisters, to “see the world” for himself, and paddle his own canoe.

Fancy a first trial trip on a tight-rope from the torch of the Statue of Liberty to Governors Island! Yet such is the corresponding feat accomplished by this self-reliant acrobat, which a few days or perhaps hours ago was but an egg!

Here is one family of spiderlings upon the grapevine spray, for instance. They are hanging several yards above the water, and with an ocean, as it were, between them and the distant country upon which their hearts are set. But there is no hesitation or misgiving. Let us closely observe this eager youngster far out upon the point of the leaf. The breeze is blowing across the brook. In an instant, upon reaching the edge of the leaf, the spiderling has thrown up the tip of its body, and a tiny, glistening stream is seen to pour out from its group of spinnerets. Farther and farther it floats, waving across the water like a pennant. Two, three, five, ten, fifteen feet are now seen glistening in the sun. Now it floats in among the herbage upon the opposite bank, and seems reaching out for a foothold. In a minute more its tip has brushed against a tall group of asters, and clings fast, the loose span sagging in the breeze, and as we turn our attention to the spider, we see that he has turned about, and is now “hauling in the slack,” which he continues to do until the span is taut, when he anchors it firmly to the leaf, and without a moment’s ceremony steps out upon his tight-rope, and makes the “trial trip” across the abyss —a feat which Dr. McCook, the spider specialist and historian, has most felicitously compared to the similar trial trip of Engineer Farrington across the cable of the East River Bridge, a thrilling event which was witnessed by thousands of spectators from sailing craft and housetops.

Our spider has now reached the asters twenty feet away, and is doubtless busying himself by further securing the anchorage at this terminus. It is quickly done, for see, he is even now far out over the water on his return trip, arriving at the grape leaf a moment later. His strand is now three times as strong as at first, and will be many times stronger before he is satisfied with it. An hour later, if we care to go up-stream half a mile to the bridge, or half a mile below to the crossing pole, for the sake of examining those asters across the brook, we shall find our spiderling nicely settled in a tiny little home of his own. The glistening span is now like a tough silken thread, and is moored to the head of flowers by a half-dozen guy-threads in all directions, while in their midst, in the “nave of his tiny wheel of lace,” our smart young baby rests from his labors.

Such is the probable course which he would follow, unless, perhaps, his roving spirit, thus tempted, has further asserted itself, and not content with this exploit, he has concluded to span the clouds, and is even now sailing a thousand feet aloft in his “ balloon.”

As a bridge-builder he has had many successful imitators, but as a balloonist he is yet more than a match for his bigger copyist, Homo sapiens, as I shall explain in a subsequent paper [enitled “Ballooning Spiders”].