So well is man served in the distribution of the waters and management of their movements by the forests, that forests seem almost to think. The forest is an eternal mediator between winds and gravity in their never-ending struggle for the possession of the waters. The forest seems to try to take the intermittent and ever-varying rainfall and send the collected waters in slow and steady streams back to the sea.

I return to Enos Mills, at last, gladly encountering an old friend. The self-styled “John Muir of the Rockies”, MIlls shares amazing (almost unbelievable) survival stories in the mountains, many of which begin with a crazy act on his end (hiking up to the high country without his snowshoes, for instance) followed by a crazy dash across the landscape, outriding an avalanche or hurrying to the nearest medical assistance — in the dark off-trail — after drinking from a spring containing some sort of toxic substance (probably heavy metals). I do not know how he survived so long to write so many books. But I am grateful that he did. And I will be back to read more of his work in the future.

While Conrad Abbott stifles me with his dense, actionless prose, Mills is always on the go. When not quoting Muir, he is emulating him, consciously or otherwise. Perhaps you recall John Muir, in The Mountains of California, clinging onto the top of an ancient Douglas spruce in a thunderstorm, exulting in the elemental forces at play? Here is Mills’ own version, in the Rockies:

The summit of the forested slope was comparatively smooth where I gained it, and contained a few small, ragged-edged, grassy spaces among its spruces and firs. The wind was blowing and the low clouds pressed, hurried along the ground, whirled through the grassy places, and were driven and dragged swiftly among the trees. I was in the lower margin of cloud, and it was like a wet, gray night. Nothing could be seen clearly, even at a few feet, and every breath I took was like swallowing a saturated sponge.

These conditions did not last long, for a wind- surge completely rent the clouds and gave me a glimpse of the blue, sun-filled sky. I hurried along the ascending trend of the ridge, hoping to get above the clouds, but they kept rising, and after I had traveled half a mile or more I gave it up. Presently I was impressed with the height of an exceptionally tall spruce that stood in the centre of a group of its companions. At once I decided to climb it and have a look over the country and cloud from its swaying top.

When half way up, the swift manner in which the tree was tracing seismographic lines through the air awakened my interest in the trunk that was holding me. Was it sound or not? At the foot appearances gave it good standing. The exercising action of ordinary winds probably toughens the wood fibres of young trees, but this one was no longer young, and the wind was high. I held an ear against the trunk and heard a humming whisper which told only of soundness. A blow with broad side of my belt axe told me that it rang true and would stand the storm and myself.

The sound brought a spectator from a spruce with broken top that stood almost within touching distance of me. In this tree was a squirrel home, and my axe had brought the owner from his hole. What an angry, comic midget he was, this Fremont squirrel ! With fierce whiskers and a rattling, choppy, jerky chatter, he came out on a dead limb that pointed toward me, and made a rush as though to annihilate me or to cause me to take hurried flight; but as I held on he found himself more “up in the air” than I was. He stopped short, shut off his chatter, and held himself at close range facing me, a picture of furious study. This scene occurred in a brief period that was undisturbed by either wind or rain. We had a good look at each other. He was every inch alive, but for a second or two both his place and expression were fixed. He sat with eyes full of telling wonder and with face that showed intense curiosity. A dash of wind and rain ended our interview, for after his explosive introduction neither of us had uttered a sound. He fled into his hole, and from this a moment later thrust forth his head; but presently he subsided and withdrew. As I began to climb again, I heard mufHed expletives from within his tree that sounded plainly like “Fool, fool, fool!”

The wind had tried hard to dislodge me, but, seated on the small limbs and astride the slender top, I held on. The tree shook and danced; splendidly we charged, circled, looped, and angled; such wild, exhilarating joy I have not elsewhere experienced. At all times I could feel in the trunk a subdued quiver or vibration, and I half believe that a tree’s greatest joys are the dances it takes with the winds.

Conditions changed while I rocked there ; the clouds rose, the wind calmed, and the rain ceased to fall. Thunder occasionally rumbled, but I was completely unprepared for the blinding flash and explosive crash of the bolt that came. The violent concussion, the wave of air which spread from it like an enormous, invisible breaker, almost knocked me over. A tall fir that stood within fifty feet of me was struck, the top whirled off, and the trunk split in rails to the ground. I quickly went back to earth, for I was eager to see the full effect of the lightning’s stroke on that tall, slender evergreen cone. With one wild, mighty stroke, in a second or less, the century-old tree tower was wrecked.

Note that Mills returns quickly to earth, not to avoid a fatal lightning strike, but out of curiosity about the tree’s fate. So like John Muir!

Beyond the adventure stories, there is another, almost scholarly, side to Enos Mills. He is an early advocate for forests — not merely as agglomerations of trees, but as entities in their own right. This holistic viewpoint enables him to recognize the many benefits — scientists today would call them ecosystem services — that forests provide. He explores these gifts in his essay, “The Wealth of the Woods”. According to Mills, these include wood supply, climate regulation, moisture retention, soil erosion prevention, air filtering/purifying, and a source of foods and medicines. In a later chapter in the book, “A Rainy Day at the Stream’s Source”, Mills ventures out in the soaking rain to observe the confluence of two streams — one densely forested, the other a recent victim of a forest fire. These early observations of the effects of forest disturbance on sediment transport in mountain streams bring to mind my own graduate research on bedload transport in a subalpine channel of the Western Slope of the Rockies in the summer of 1993, and a host of other (more noteworthy) geomorphological research over many decades. As expected, one stream flows clear, while the other is choked with sediment. I will leave the reader to guess which was which.

Mills also writes extensively about forest fires and their impacts. Though it would be most of a century before the apocalyptic infernos wrought by climate change in the West, the fires he describes were still quite intense; most were started by people (campfires, sparks from trains). Not surprisingly, Mills viewed fire almost entirely as a destructive force, one to be prevented if at all possible. However, he does acknowledge one positive effect of such fires — the formation of all the open grassy parks high in the Rocky Mountains, including his beloved Estes Park.

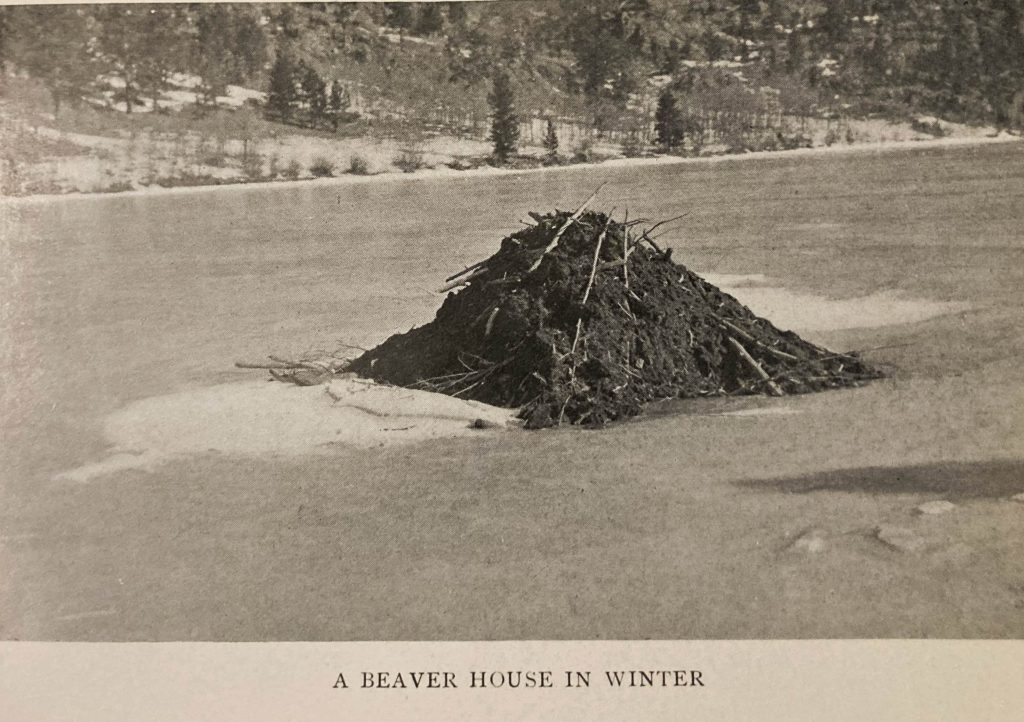

Before closing out my review of this book, I feel compelled to mention Mills’ fascination with beavers. He spent countless days closely observing them carrying out their industrial operations — logging the woods, hauling the timber, building dams, and building lodges. At one location, he observed more than forty beavers all hard at work at one time! He recognized their substantial role in modifying streams and forests. But the fascination with them went well beyond that. Here is MIlls, in one of his most charming passages, singing the praises of beavers and their world:

The beaver has a rich birthright, though born in a windowless hut of mud. Close to the primitive place of his birth the wild folk of both woods and water meet and often mingle; around it are the ever-changing, never-ending scenes and silences of the water or the shore. He grows up with the many-sided wild, playing amid the enameled flowers, the great boulders, the Ice King’s marbles, and the fallen logs in the edge of the mysterious forest; learning to swim and slide; listening to the strong, harmonious stir of wind and water; living with the stars in the sky and the stars in the pond; beginning serious life when brilliant clouds of color enrich the hills; helping to harvest the trees that wear the robes of gold, while the birds go by for the southland in the reflective autumn days. If Mother Nature should ever call me to live upon another planet I could wish that I might be born a beaver, to inhabit a house in the water.

Finally, a few words about the provenance of my copy of this book. I suspect I will never fully grasp the complex intricacies of out-of-print book pricing. For some reason, Wild Life on the Rockies is generally much cheaper than The Spell of the Rockies. Fortunately, I was able to locate a fairly intact copy; the hinges are cracked, but the binding still has a bit of life left in it. For an ex-library volume, the cover is remarkably pristine. It was long in the possession of the Toledo – Lucks County Public Library, and it bears the scars — stamps, a card pocket in the front, a sticker with a computer code. All I know about its acquisition by the library is that it was “A Gift of a Citizen of Toledo”.