To take the earth as one finds it, to plant oneself in it, to plant one’s roof-tree in it, to till it, to understand it and the laws which govern it, and the Perfection which created it, and to love it all — that is the heart of John Burroughs’ religion, the pith of his philosophy, the conclusion of his books.

In the end of March, 1921, John Burroughs passed away while on a train taking him back from California to his beloved home in New York State. A few months later, Dallas Lore Sharp, an admirer and friend of Burroughs, published this brief volume (71 pages in large print) as a eulogy to the fallen nature writer. The various copyright dates in the front (1910, 1913, 1921) hint at how it is a hastily cobbled-together affair. It says relatively little by way of biography; a good portion of the book is actually a comparison of Burroughs and Thoreau. Along the way, however, it sheds considerable light on why Burroughs was such a central figure in the literary Nature Movement of the previous half-century.

One immediate shock the reader receives, upon opening the book with its mahogany veneer cover, is the dedication: “To Henry Ford / Lover of Birds / Friend of John Burroughs”. Here, one can immediately see a difference between Thoreau and Burroughs. Thoreau, I am confident, would never have befriended a robber baron, choosing instead to advocate for the “common man”. I am certain that Ford’s political views would have sat very uneasy with Thoreau. But for Burroughs, largely free of political views, it was a marvelous thing to ride about the countryside in a Model T given t him by Henry Ford.

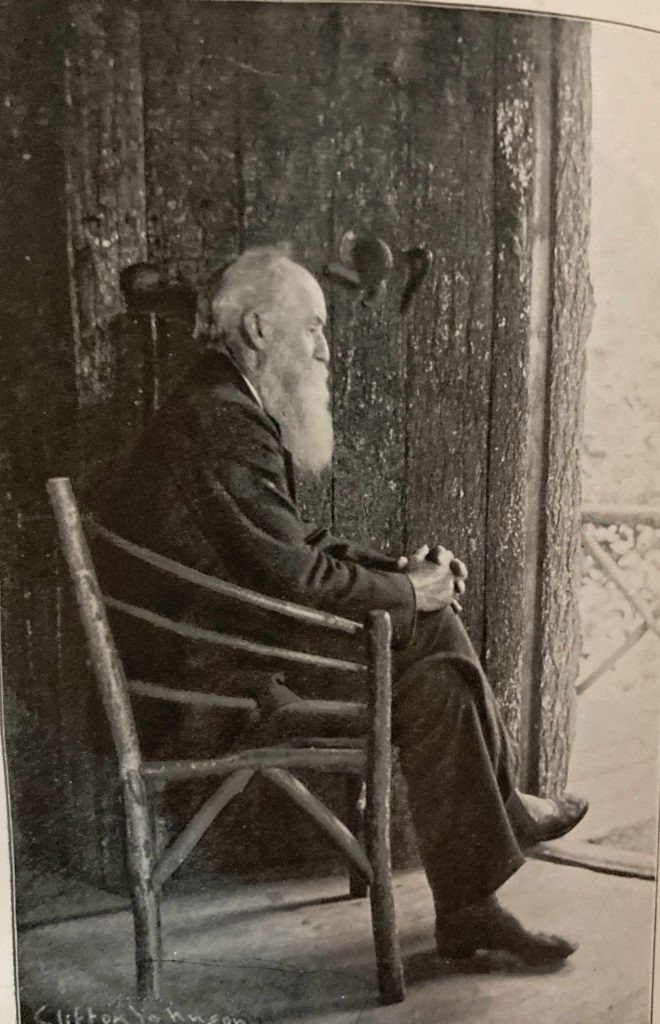

As Sharp describes Burroughs early in the book, “He loved much, observed and interpreted much, speculated a little, and dreamed none at all.” He was a “…teacher and interpreter of the simple and the near at hand.” He brought a sense of wonder and curiosity to all that he encountered. According to Sharp, during his last visit with Burroughs a few months before the writer’s death, the two noticed a woodchuck, and Burroughs remarked, “How eternally interesting life is! I’ve studied the woodchuck my whole life, and there’s no getting to the bottom of him.” In various essays, he shed particular light on facets of the natural world, from woodchucks to bluebirds. Over 50 years, Burroughs produced what Sharp describes as “…beyond dispute, the most complete, the most revealing of all our outdoor literature.” Ultimately, Burroughs was after the whole of nature, more than just its individual living components: “His theme has not been this or that, but nature in its totality, as it is held within the circle of his horizon, as it surrounds, supports, and quickens him.”

A few pages later, Sharp presents the argument that the “modern” (i.e., 1921) nature writer model has its roots in Burroughs: “The essay whos matter is nature, whose moral is human, whose manner is strictly literary, belongs to John Burroughs.” As practiced by Burroughs, Sharp explains, good outdoor writing demonstrated both fidelity to fact and sincerity of expression. Sharp proposes two questions for testing all nature writing: 1) Is the record true?; and 2) Is the writing honest?

At this point, Thoreau enters the scene. In the next dozen pages or so, Sharp argues (without slighting Thoreau) that the founding figure of the Nature Movement is not Thoreau, but Burroughs. Thoreau’s thoughts were lofty, his demeanor iconoclastic. Burroughs was companionable and firmly grounded in everyday realities, with a prose style immediately accessible to the general public. In writing about their own garden or woodlot and observing the birds and trees, aspiring nature writers could hope to emulate Burroughs’ tone and voice; Thoreau’s was out of reach. “Burroughs takes us along with him,” Sharp explains, “Thoreau comes upon us in the woods, jumps out at us from behind some bush, with a ‘Scat!’ Burroughs brings us home in time for tea; Thoreau leaves us tangled up in the briars.” Thoreau hoed beans as a reenactment of the roots of civilization; Burroughs maintained an 18-acre vineyard and made a living from it. As Burroughs himself once asserted, “Thoreau is nearer the stars than I am.” Sharp follows with this vivid comparison of “…Thoreau, searching by night and day in all wild places for his lost horse and hound, while Burroughs quietly worshipped, as his rural divinity, the ruminating cow.” Burroughs made no new discoveries, but he saw old things anew and invited others to do the same.

As a closing observation, Sharp noted that there were many themes in Burroughs’ works, but only one central message: “…that this is a good world to live in; that these are good men and women to live with; that life is good; here and now, and altogether worth living.”

My somewhat weatherbeaten copy of this book bears no dedications or signatures but does have a tiny bookseller’s label from Dennen’s Book Shop, 37 East Grand River Avenue, Detroit, Michigan. Whoever owned the book at very least had it off the shelf for a time; there is some water staining along the edges of the first few pages, and the first half of the book has a gentle fold. But toward the end of the brief volume, I still found an uncut page.

I felt ever so in touch with an incredibly relevant piece. Thank you for your contribution.

Thank you so much, Craig. I am really enjoying reading some of these forgotten authors — I find much insight and wonder in the journey.