A colleague of mine (long deceased) introduced me to the author of this fascinating little book. I am speaking here of Horace Lunt, who shared some observations of birds and referenced “Mr. Minot” in his 1891 Short Cuts and By-Paths. The name Minot seemed oddly familiar already; in fact, Minot is a small city in eastern North Dakota, which happens to have been named after him. Henry Davis Minot (1859-1890), was a railroad financier and ornithologist. He had an adventuresome and productive though tragically brief life. At Harvard, he met Theodore Roosevelt, and the two become fast friends and traveling companions. After two years enrolled there, Minot left for a lucrative career in the railroad industry, which required extensive travel. Everywhere he went, he recorded the birds he observed. He published several full-length works on birds, beginning with Land Birds and Game Birds of New England, published when he was just 18. Three years later, he published the booklet, The Diary of a Bird. Ten years later he was dead, killed instantly in a railroad collision in Pennsylvania.

Holding it in my hands, The Diary of a Bird feels precious and fragile. Two small staples and a bit of glue (and now, a piece of archival-quality transparent tape) are all that hold it together. Apart from the inevitable browning and a smudge or two, my copy of the booklet is without a blemish. It astounds me that this little volume (selling for 25 cents in 1880 — about $7.16 today) managed to survive 142 years so unscathed. There are no bent pages, no pen or pencil marks, and no stains of coffee or tea. I have no idea how many copies remain; online, I found an image of only one, with much greater wear than this. It was offered at $25 on eBay, and I negotiated to $18. But how does one put a dollar value on something so unusual and underappreciated as this?

At the age of 21, Henry Davis Minot had already seen firsthand the peril America’s birds faced. Young and brash and wanting to do something about the problem, he wrote The Diary of a Bird, sending copies to renowned naturalists of the time, including Samuel Lockwood and John Burroughs. He hoped that the booklet of only thirty-eight pages would raise awareness of the birds’ plight and prompt action. As a work of early environmental conservation, it has been virtually forgotten (as has, I have found through my reading and research, so much of early efforts to protect bison and birds). A charming blog entry from the Massachusetts Historical Society tells Minot’s story, suggesting that his untimely death prevented him from doing more to safeguard America’s birds.

The booklet itself is difficult to categorize. Ostensibly a diary of a black-throated green warbler (“translated” by Minot), it opens with a remark by the “writer” that “I am aware that among men the keeping of a diary is ordinarily a way of misspending a part of one’s time in describing how one has wasted the rest. I disapprove of diaries among birds; yet I have decided to keep one for the purpose of amusing, instructing, and enlightening mankind.” The first few pages chronicle the bird’s arrival in the White Mountains after a long migration from the South, and his mate’s efforts to build a nest and rear their young (with his occasional support). In one early passage, the bird (who has no name, in keeping with all birds) complains about all the white pines that have been lost to logging. He also has a brief run-in with a birder, who is after his feathers for a lady’s hat.

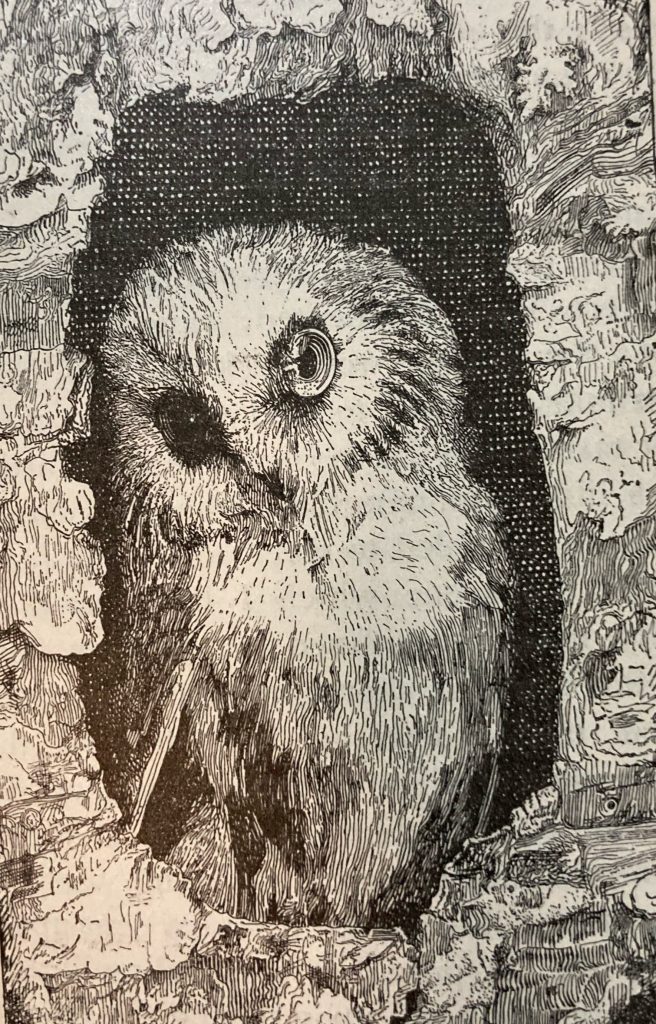

The heart of the booklet concerns a gathering of birds in the woods to discuss The Destruction and Extermination of Birds: how caused, and how to be prevented. Each bird, in turn, shares its greatest threat; these include hunters, egg collectors, domestic cats, and lighthouse collisions. The black-throated green warbler is about to speak when hunters arrive, and the protagonist shelters in a tree cavity an owl had previously occupied. The translator interjects at this point, with statistics on bird deaths for the state of Massachusetts, concluding that humans killed approximately a quarter-million wild birds (including eggs) every year. After quoting other writers on the extent of the problem. the translator offers solutions:

How are the ravages to be checked? By arousing the better sentiment of the people, so, for instance, that birds shall be practically protected for other purposes than mere sport; by having a sufficient police to enforce the present laws, so as to prevent the wanton or illegal destruction of birds and eggs; by more descriminate, effective, and extensive legislation.

Minot goes on to call for an effective game commissioner for every state, and, wonder of wonders, a tax on firearms, “a tax which would prevent, among many other things, many accidents caused by such comparatively useless weapons as pistols.” But even that does not go far enough. “The best law for Massachusetts,” Minot declares, “would be one prohibiting the firing of a shot-gun within the state, for a term of years. (We say this advisedly after thought and consultation.)”

The translator steps aside to allow the warbler gets the last word. In a final diary entry, he makes this plea: “I trust that he to whom these pages are to be consigned, one who, as a sincere lover of Nature, seems to understand our language and to know our ways, will make some appeal to his fellow-men, in behalf of us poor, unhappy, persecuted birds.”

The pauses in the midst of a railroad-man’s management career is a reminder to us all: learn to listen and observe the world closely AND make something of it. I feel as if I still have a long way to go to be that successful.