The book that started me on this peculiar quest to resurrect long-dead obscure nature writers was In American Fields and Forests, published by Houghton-Mifflin in 1909. It was an anthology of six American nature writers. Two have retained their renown to this day — Henry David Thoreau and John Muir. One was quite famous at the time and, though largely forgotten today, still has several works in print — John Burroughs. (He will soon become a regular in this blog — more on that anon.) The remaining three are lost to the history of nature writing, though I hope to change that in some small way. They were Bradford Torrey, Dallas Lore Sharp, and Olive Thorne Miller. I have already read several books by Torrey and Sharp (with others waiting on my shelf). But I have been putting off Olive Thorne Miller, until now.

Harriet Mann Miller (1831-1918) published several books on birds under the pen name of Olive Thorne Miller. She had a fairly uneventful childhood (apart from moving every few years), then married Watts Todd Miller, bore and raised four children, and wrote several children’s books. She was introduced to ornithology by Sara Hubbard (director of the Illinois Audobon Society) in 1880 and quickly became an avid bird watcher. She wrote eleven bird books between 1885 and 1904. I have obtained four but have been putting them off for one simple reason: I hereby confess that I am not a birder. I appreciate birds — their colorful forms, fascinating behaviors, lovely songs (and raucous cries). I am particularly fond of American cranes, sandhill and whooping. Hawks and eagles are stunning, and the intelligence of crows gives me pause. But I cannot identify birds by call, and I have a minimal capacity for spotting birds calling in dense foliage. I know a dozen bird species — and a dozen more that are found along the Maine Coast, courtesy of a summer narrating puffin tours for Project Puffin many years back. But I am quite frankly intimidated by birders — their expensive cameras with telephoto lenses that look like they might have cost more than my house, their fascination with life lists, and their stunning capacities for identifying birds from faint calls or a momentary flash of color in a tree. OK, I admit it: they intimidate me. I will stick to insects and plants. I have yet to meet a botanist with special camera equipment to capture chestnut trees or May apples, bearing a life-list of plant species they have encountered or able to identify any plant from the merest fragment of a leaf.

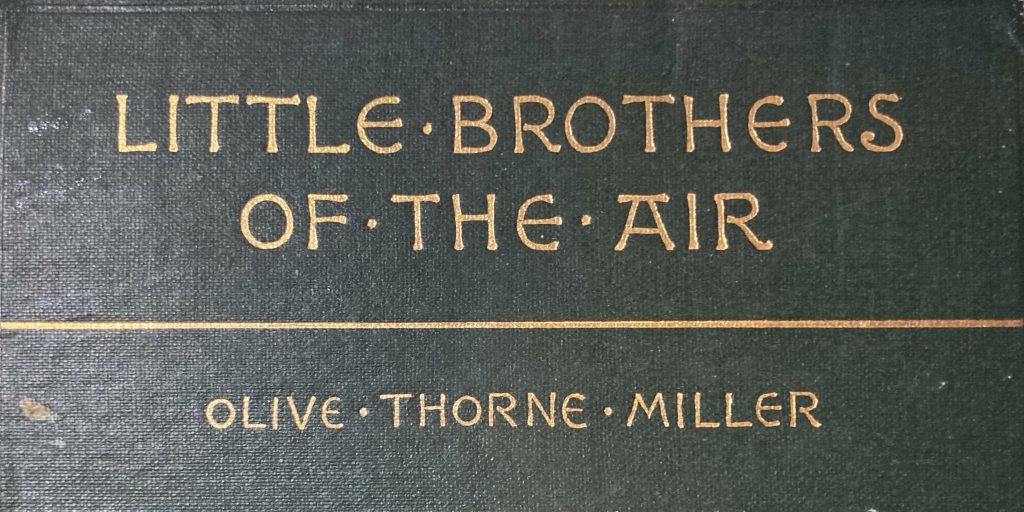

So I have been putting off reading Miller’s work, even while I managed to accrue four of her titles, including her first and last bird books (Little Brothers of the Air was her second one.) I am doing my best to track down early women natural history writers, of which there were quite a few. So I didn’t want to ignore her completely. And Torrey was mostly an ornithologist, so I have already read books laden with passing bird descriptions. In an age before photography was readily available and easy to use in the field, ornithological writers provided rich text descriptions of the birds they saw — all of which fled my mind the moment I read them. Torrey’s books don’t have illustrations, and neither does this volume by Miller. So text is practically all there is to paint the scene and the feathered beings inhabiting it.

I am proud to say that I survived Little Brothers of the Air, though I am in no hurry to read the remaining three books of hers in my collection. She was a fine writer and notable for her independence and spirit of scientific inquiry. While some of her field outings were accompanied by a companion or two (usually female), many of her nature outings were solitary affairs. She was highly dedicated to closely observing birds, which might mean watching a nest through an opera-glass for one or two weeks at a time (or even, in one case, two months!). (“One must be an enthusiast to spy out the secrets of a bird’s life,” she remarks at one point.) Here she describes the privations she underwent in her nature studies:

Didst ever, dear reader, sit in one position on a camp-stool without a back, with head thrown back, and eyes fixed upon one small bird thirty feet from the ground, afraid to move or turn your eyes, lest you miss what you are waiting for, while the sun moves steadily on till his hottest rays pour through some opening directly upon you; while mosquitoes sing about your ears (would that they sang only!), and flies buzz noisily before your face; while birds flit past, and strange notes sound from behind; while rustling in the dead leaves at your feet suggests snakes, and a crawling on your neck proclaims spiders? If you have not, you can never appreciate the enthusiasms of a bird student, nor realize what neck-breaks and other discomforts one will cheerily endure to witness the first flight of a nestling.

The volume is a collection of vignettes of bird behavior, particularly nesting. Some chapters chronicle her observations of a particular nest, from construction through the fledging of the young — or not. She reported that, over a season, about half the nests she watched failed to produce young, often due to the depredations of chipmunks, other birds, or a couple of neighbor boys who stole eggs from nests. Other chapters are based on her travels in New England. She would stay in a friend’s cabin and set out every day to make her acquaintance with all the bird species in the area. Along the way, she might also describe the landscape and vegetation features, offering a delightful reprieve from all the feathers flying.

Occasionally, too, she would complain about something; I enjoyed this feisty side to her nature. She complained about farmers logging their wood lots, though she admitted that the lumber provided a valuable income from their point of view. She complained about farmers replacing old zig-zag stone walls with barbed wire fences: “Nature doesn’t take kindly to barbed wire.” She complained vigorously about the lack of nature knowledge among country folk: “A chapter might be written on the ignorance of country people of their own birds and plants. A chapter, did I say? A book, a dozen books, the country is full of material.” Finally, she also complained about how naturalists like to name everything (a bit ironic, given her own tendency to do so):

Why have we such a rage for labeling and cataloguing the beautiful things of Nature? Why can I not delight in a bird or flower, knowing it by what it is to me, without longing to know what it has been to some other person? What pleasure can it afford to one not making a scientific study of birds to see such names as “the blue and yellow-throated warbler,” “the chestnut-headed golden warbler,” “the yellow-bellied, red-poll warbler,” attached to the smallest and daintiest beauties of the woods?

Before I close the covers of this unassuming green cloth volume with gilt letters on the cover, I ought to say a few words about Miller’s descriptive style. Her careful observation of birds is evident on every page. However, she also frequently goes beyond mere action to interpretation — investing particular behaviors with motivations. Frequently, those motivations mirror human ones. Sometimes, the result is a bit disconcerting to the modern reader, used to reading about birds as non-human beings rather than as quasi-human persons. For example, she describes a male kingbird as singing to his mate while she is brooding her eggs to encourage her in the task. Elsewhere, she describes a young bluebird who “talked with himself for company, a very charming monologue in the inimitable bluebird tone. with modifications suggesting that a new and wonderful song was possible to him. He was evidently too full of joy to keep still.” On rare occasions, she endeavors to offer justification for her accounts. For example, in one of the last essays in the volume, she describes the behaviors of a pair of goldfinches. The female sat on the eggs, and the male would show up whenever she called to him. He would fly above her, trying to locate other birds that might be annoying her.

Sometimes that conduct did not reassure the uneasy bird, and she called again. Then he brought some tidbit in his beak, went to the edge of the nest, and fed her. Then she was pacified; but do not mistake her, it was not hunger that prompted her actions; when she was hungry, she openly left her nest and went for food. It was, as I am convinced. the longing desire to know that he was near her, that he was still anxious t serve her, that he had not forgotten her in her long absence from his side. This may sound a litle fanciful to one who has not studied birds closely, but she was so “human” in all her actions that I feel justified in judging of her motives exactly as I should judge had she measured five feet instead of five inches, and wore silk instead of feathers.”

Miller’s confidence in drawing such brazen parallels between bird behavior and human behavior does strike me as somewhat far-fetched at times. Of course, one could argue that this kind of personification of animals was common back then and would only become more pronounced by the time of the “nature faker” controversy a decade later. Furthermore, whatever the actual motives behind them, the birds’ actions themselves were painstakingly observed and (generally speaking) accurately described. I am confident, too, that her books encouraged many a reader to take up a notebook and opera-glass, and venture into the local woods and fields.

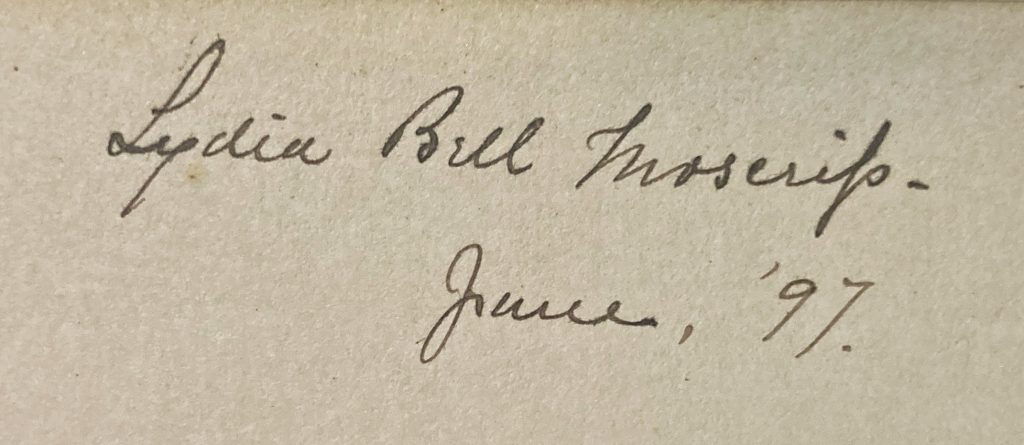

My copy of Little Brothers of the Air is in great condition for its age. The blank page after the flyleaf bears the signature of Lydia Bell Moscrif, June, ’97.