Our forests by daylight are rapidly being thinned into picnic groves; the bears and panthers have disappeared, and by day there is nothing to fear, nothing to give our imaginations exercise. But the night remains, and if we hunger for adventure, why, besides the night, here is the skunk; and the two offer a pretty sure chance for excitement. Never to have stood face to face in a narrow path at night with a full-grown, leisurely skunk is to have missed excitement and suspense second only to the staring out of countenance of a green-eyed wildcat. It is surely worth while, in these days of parks and chipmunks, when all stir and adventure has left the woods, to sally out at night for the mere sake of meeting a skunk, for the shock of standing before a beast that will not give you the path. As you back away from him you feel as if you really were escaping. If there is any genuine adventure left for us in this age of suburbs, we must be helped to it by the dark.

WRITTEN AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY (1901), THESE WORDS REFLECT THE RAPIDLY TRANSFORMING LANDSCAPE OF THE EASTERN SEABOARD OF THE UNITED STATES. From his home in New Jersey, Sharp bore witness to an age of urbanization and suburbanization. Wild woodlands were rapidly disappearing, replaced with orchards, fields, and city blocks. For Sharp, this change meant a dramatic shift, largely positive, in the state of America’s songbirds, as he saw more and more of them learning how to co-exist with humans. and their constructions. At the same time, he bemoaned the rapid disappearance of mammals and raptors, a situation he saw as inevitably becoming worse over time. And these changes would be a tremendous loss to all Americans:

I wish the game-laws could be amended to cover every wild animal left to us. In spite of laws they are destined to disappear; but if the fox, weasel, mink and skunk, the hawks and owls, were protected as the quail and deer are, they might be preserved a long time to our meadows and woods. How irreparable the loss to our landscape is the extinction of the great golden eagle! How much less of spirit, daring, courage, and life come to us since we no longer mark the majestic creature soaring among the clouds, the monarch of the skies! A dreary world it will be out of doors when we can hear no more the scream of the hawks, can no longer find the tracks of the coon, nor follow a fox to den.

On the other hand,

There is promise of a future for the birds in their friendship with us and in our interest and sentiment for them. Everybody is interested in birds; everybody loves them. There are bird-books and bird-books and bird-books — new volumes in every publisher’s spring announcements. Every one with wood ways knows the songs and nests of the more common species.

In fact, Sharp gloried in the extent to which he saw so many bird species adapting to a human presence. When a friend declared to him that the birds would all soon be extinct because “Civilization is bound to sweep them away,” Sharp

made no reply, but, for an answer, led the way to the street and down the track to this pole which High-hole [a northern flicker] had appropriated. I pointed out his hole, and asked them to watch. Then I knocked. Instantly a red head appeared at the opening. High-hole was mad enough to eat us; but he changed his mind, and with a bored, testy flip, dived into the woods. He had served my purpose, however, for his read head sticking out of a hole in a street-railway pole was a rising sun in the east of my friend’s ornithological world, New light broke over this question of birds and men…..

High-hole is a civilized bird. Perhaps “domesticated” would better describe him; though domesticated implies the purposeful effort of man to change character and habits, while the changes which have come over High-hole — and over most of the wild birds — are the result of High-hole’s own free choosing.

If we should let the birds have their way they would voluntarily fall into civilized, if not into domesticated, habits.

As evidence of this, Sharp highlights the avian riches in his own “civilized” backyard:

Using my home for a center, you may describe a circle of a quarter-mile radius and all the way round find that radius intersecting either a house, a dooryard, or an orchard. Yet within this small and settled area I found one summer thirty-six species of birds nesting. Can any cabin in the Adirondacks open its window to more voices — any square mile of solid, unhacked forest on the globe show richer, gayer variety of bird life?

In fact, orchards are particularly rich with avian fauna:

Except for the warblers, one acre of apple-trees is richer in the variety of its birds than ten acres of woods.

FORTUNATELY, SHARP’S PROGNOSTICATIONS CONCERNING THE FUTURE OF AMERICA’S RAPTORS AND MAMMALS WERE WILDLY INACCURATE. And fortunately, too, his claims about the degree to which birds adapt joyously to humans (to the point that wildlands become largely unnecessary for their continuance) appear to have been ignored. Still, in the midst of all the pessimism about the future of America’s wildlife that i have encountered in many other writers from this time, Sharp’s hopefulness and positive outlook on the human impact on nature was refreshing.

UNFORTUNATELY, FOR A VARIETY OF REASONS, I FOUND SHARP HIMSELF RATHER UNLIKEABLE. I know I ought to be open-minded toward others, particularly those that have been dead for almost a century. I kept trying to, even after the opening chapter ended with the shooting of several muskrats. In another essay, Sharp encounters an opossum in a hollow tree — and dines on him the next day. He writes about how toads are “unlovely” and “repulsive”, but how we should still learn to appreciate them for their other qualities. The final straw, though, is a random attack on those who love old books. How dare he?

An ardor for decayed trees is not from any perversity of nature. There is nothing unreasonable in it, as in — bibliomania, for instance. I discover a gaunt, punky old pine, bored full of holes, and standing among acres of green, characterless companions, with the held breath, the jumping pulse, the bulging eyes of a collector stumbling upon a Caxton in a latest-publication book-store. But my excitement is really for some cause; for — sh! look! In that round hole up there, just under the broken limb, the flame of the red-headed woodpecker — a light in one of the windows of the woods. Peep through it. What rooms! What people! No; I never paid ten cents extra for a volume because it was full of years and mildew and rare errata (I sometimes buy books at a reduction for these accidents); but I have walked miles, and passed forests of green, good-looking trees, to wait in the slim shade of some tottering, limbless old stump.

While I respect his attempt to juxtapose dead wood (trees) with dead paper (books) as a means of highlighting the life present in an old snag, as one who is equal parts lover of books and of nature, I will continue to find delight in both.

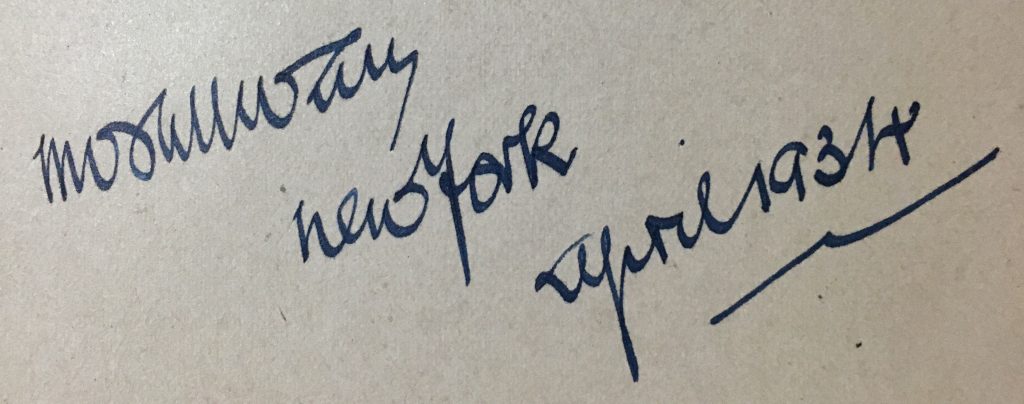

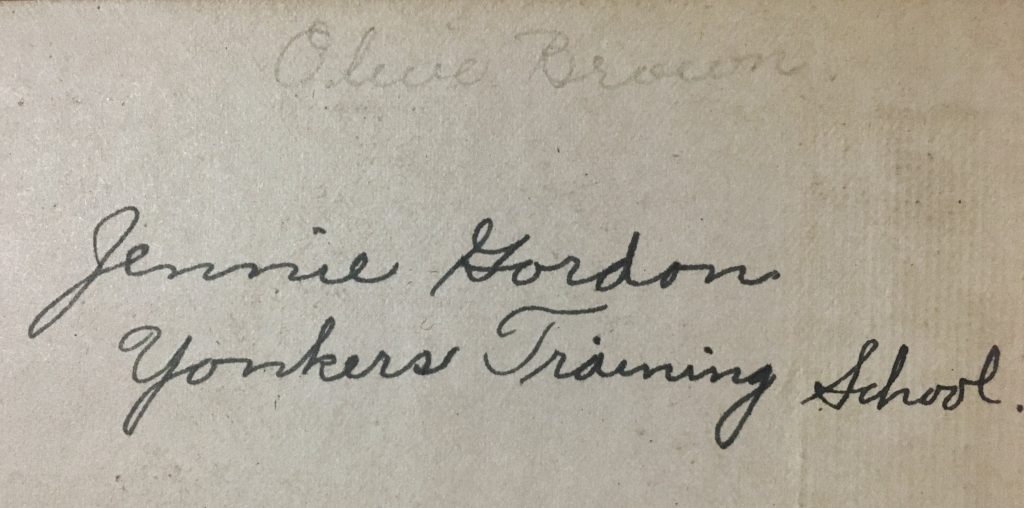

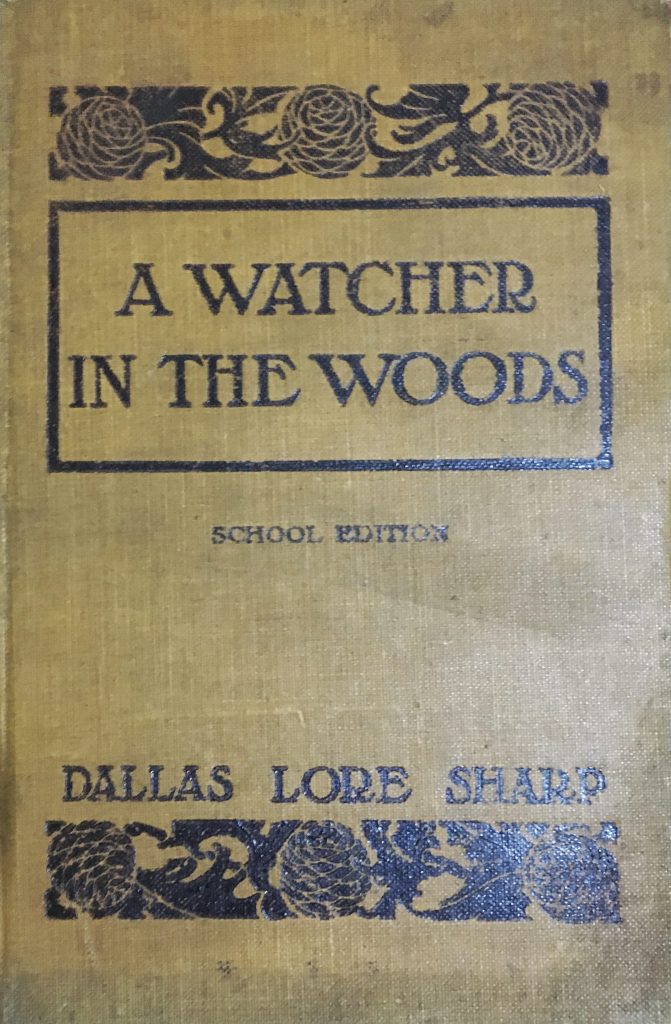

WHICH BRINGS ME TO THE COPY OF THIS BOOK THAT I READ. First, a clarification regarding the age of the text, though. A prolific writer of nature essays celebrating the local wonders of each season, Sharp published “Wild Life Near Home” in 1901, and then put out a thinner volume of excerpted pieces as “A Watcher in the Woods” two years later. In 1911, the Century Company published a School Edition — a slender volume without illustrations, but including notes and suggestions for teachers at the end. This particular edition appears to have been in the possession of an Ollie Brown (written in pencil, mostly erased) and (probably later) a Jennie Gordon from Yonkers Training School. Another person’s handwriting appears in fountain pen on the flyleaf, writing an indecipherable line (if anyone reading this can interpret it, please let me know what it says), followed by New York, followed by April 1934. That is all I know of this book’s history.