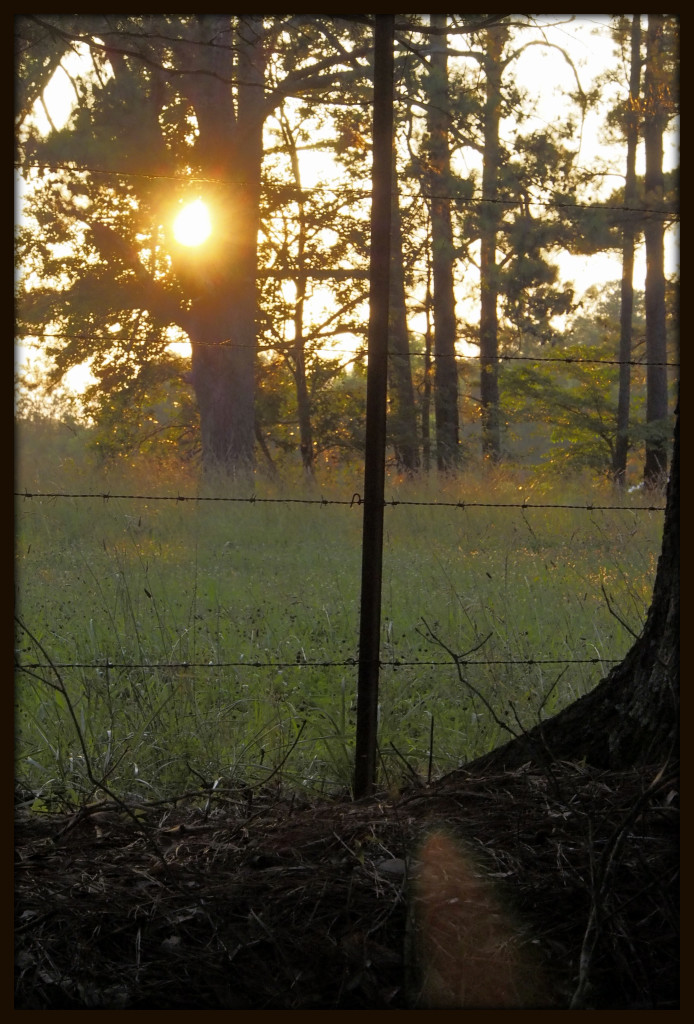

I arrived to Piney Woods Church Road near sunset, after an evening thunderstorm. The lighting was marvelous; for a few minutes, the sun on its descent emerged from the clouds to shine a brilliant yellow-orange low in the sky.

I arrived to Piney Woods Church Road near sunset, after an evening thunderstorm. The lighting was marvelous; for a few minutes, the sun on its descent emerged from the clouds to shine a brilliant yellow-orange low in the sky.

Here is a charming beetle that I encountered resting placidly on a muscadine grape leaf. I have since learned, with assistance from Facebook folks at BugGuide, that it is a click beetle, Megapenthes limbalis.

I felt compelled to photograph this unusual frond of ebony spleenwort (Asplenium platyneuron), which had developed a bend during its growth.

Here are two radiant photographs, gifts of the golden hour before sunset.

Late this afternoon I sauntered down Piney Woods Church Road, hoping to obtain a few photos of plant leaves in golden-hour sunlight. I was startled — and delighted — to see young calves out in the pasture with their mothers. According to a neighbor, the calves are probably less than a week old. In this photograph, a new mother nuzzles her young charge.

There is much to be said for leaving a lawn untouched. First there is the matter of money and labor associated with applying various fertilizers and weed-killers. Then there is the blatant fact that a well-tended lawn is boring. It is analogous to an outdoor carpet: single tone of color, a few species of grasses (perhaps only one), few insects (and therefore few insect predators as well). But if one leaves a lawn alone, wonderful things can begin to happen.

There is much to be said for leaving a lawn untouched. First there is the matter of money and labor associated with applying various fertilizers and weed-killers. Then there is the blatant fact that a well-tended lawn is boring. It is analogous to an outdoor carpet: single tone of color, a few species of grasses (perhaps only one), few insects (and therefore few insect predators as well). But if one leaves a lawn alone, wonderful things can begin to happen.

Yes, there is the inevitable crabgrass and Bermuda grass, seedlings of sweet gum and loblolly pine, and pokeweed resolutely striving to gain a foothold. Then there are the invasive plants — most noticeably in this Chattahoochee Hills yard, honeysuckle and privet. But there are also annual and perennial wildflowers of meadow and roadside that begin to make an appearance. Given time, dry ground, and plenty of sunlight, an orchid might even grow in the yard.

And that is how, after several years of a lawn-care regimen consisting of mowing perhaps four times every summer but otherwise leaving the grass alone, several ladies’ tresses appeared in this writer’s lawn. More specifically, they were little ladies’ tresses, also known as little pearl-twist (Spiranthes tuberosa). Found from Texas to Massachusetts and Kansas to Florida, little ladies’ tresses is one of 17 species of ladies’ tresses present in the Southeast. Even trained botanists sometimes have great difficulty telling the different species (not to mention their hybrids) apart; fortunately, the little ladies’ tresses is the only member of the genus that blooms at midsummer here in Georgia, and is also unique for not having its basal leaves present during flowering. Most other members of Spiranthes (even the misnamed spring ladies’ tresses, Spiranthes vernalis) bloom in late summer or early autumn, and retain their leaves all summer long.

Ladies’ tresses are lovely not so much for their flowers as for the elegant form of their presentation on the stalk. The individual flowers are pure white, very small (about 4 mm long) and otherwise unspectacular; however, they are arranged in a lovely spiral pattern. That is the origin of the genus name Spiranthes, which means “coil flower”. There is much variability from one plant to the next. Some have their blooms arrayed in multiple tight spirals, twisted to the point that they seem to be in three or four columns. Others have no spiral at all, forming a single column on one side of the stalk. The most striking, to this writer’s eye, are the ones that have two or three gentle spirals of flowers running up the stalk in waves.

One particular little ladies’ tresses was being visited by a small beetle when the author photographed it on a morning in mid-June (see photograph on the right). The beetle was metallic black in color, and less about half a centimeter long, and perched on one of the flower blossoms. According to An Atlas of Orchid Pollination by Nelis Cingel, orchids in the genus Spiranthes are all pollinated by long-tongued bees, including some halictid bees (also called “sweat bees”) and bumblebees. What, then, was the beetle doing there? Beetles are exceedingly diverse and usually quite difficult to identify down to the species or even genus level. With that caveat, it was probably a ground beetle in the genus Cymindis. Unique among the ground beetles, species of Cymindis tend to be active during the daytime, and visible on flowers and foliage. They do not drink nectar, but instead feed on insects such as plant lice. It is possible that this particular beetle was hunting for a meal, or perhaps just resting at a particularly beautiful spot.

One particular little ladies’ tresses was being visited by a small beetle when the author photographed it on a morning in mid-June (see photograph on the right). The beetle was metallic black in color, and less about half a centimeter long, and perched on one of the flower blossoms. According to An Atlas of Orchid Pollination by Nelis Cingel, orchids in the genus Spiranthes are all pollinated by long-tongued bees, including some halictid bees (also called “sweat bees”) and bumblebees. What, then, was the beetle doing there? Beetles are exceedingly diverse and usually quite difficult to identify down to the species or even genus level. With that caveat, it was probably a ground beetle in the genus Cymindis. Unique among the ground beetles, species of Cymindis tend to be active during the daytime, and visible on flowers and foliage. They do not drink nectar, but instead feed on insects such as plant lice. It is possible that this particular beetle was hunting for a meal, or perhaps just resting at a particularly beautiful spot.

This article was originally published on June 29, 2010.

I have passed this moss- and lichen-encrusted boulder of granite for 166 days now, and at last, I include its photograph. My first love was geology, and one of the landscape features I miss most along Piney Woods Church Road is a fresh roadcut, a spot where a road has been blasted or bulldozed through the local bedrock. This boulder is the largest geological specimen on my daily walk. At several hundred million years old, it truly is a Rock of Ages.

I continue to be intrigued by the many twists and turns of the tendrils of muscadine grapevine (Vitis rotundifolia). The more attention I pay to them, the more I begin to wonder at patterns I notice. For example, it seems as if all the bright red tendrils are located near the top of the vine, in places exposed to direct sunlight. The tendrils lower down on the plan tend toward much paler red or even green. I wonder if the red tendrils contain a photosynthetic pigment that the green ones do not. Something to research further….

Today as I strolled along the Piney Woods Church Road drainage ditch, I glimpsed this yellow flower by the side of the ditch. I later identified it as Goatsbeard, (Tragopogon pratensis). Another immigrant from Europe, it is also called Showy Yellow Goatsbeard to distinguish it from Yellow Goatsbeard (also from Europe). To add further confusion, there are half a dozen other common names routinely applied to one or the other of the two plants, making a very good argument for the benefit of using Latin taxonomic names instead. Goatsbeard earned its common name, I suspect, because of its airy, dandelion-like seed ball, three inches across.

My favorite image from this afternoon’s Piney Woods Church Road walk is this dried and curled bit of water oak leaf.