The literary naturalist does not take liberties with facts; facts are the flora upon which he lives. The more and the fresher the facts the better. I can do nothing without them, but I must give them my own flavor. I must impart to them a quality which heightens and intensifies them.

To interpret Nature is not to improve upon her: it is to draw her out; it is to have an emotional intercourse with her, absorb her, and reproduce her tinged with the colors of the spirit.

Thus states John Burroughs (1837-1921) in the introduction to his first nature book, Wake-Robin. Presented as “mainly a book about the Birds,” Burroughs actually took his title from the local flora, with a name evoking the birds but also suggesting a broader view of the natural world. Ironically, given his statement about not taking liberties with facts, in this case, John Burroughs was in error; he defines wake-robin as “the common name of the white Trillium, which blooms in all our woods, and which marks the arrival of all the birds.” However, as shown above, the wake-robin trillium is actually dark red, with a nodding flowerhead. Here I would grant Burroughs some slack; the book was actually written far away from his native New York State, while he was working as a clerk in Washington, D.C. In the introduction, he described his writing place: “I was the keeper of a vault in which many millions of bank-notes were stored. During my long periods of leisure I took refuge in my pen. How my mind reacted from the iron wall in front of me, and sought solace in memories of all the birds and of summer fields and woods!” I am confident I could not compose essays so evocative of the natural world of these while facing a bank vault door hundreds of miles away.

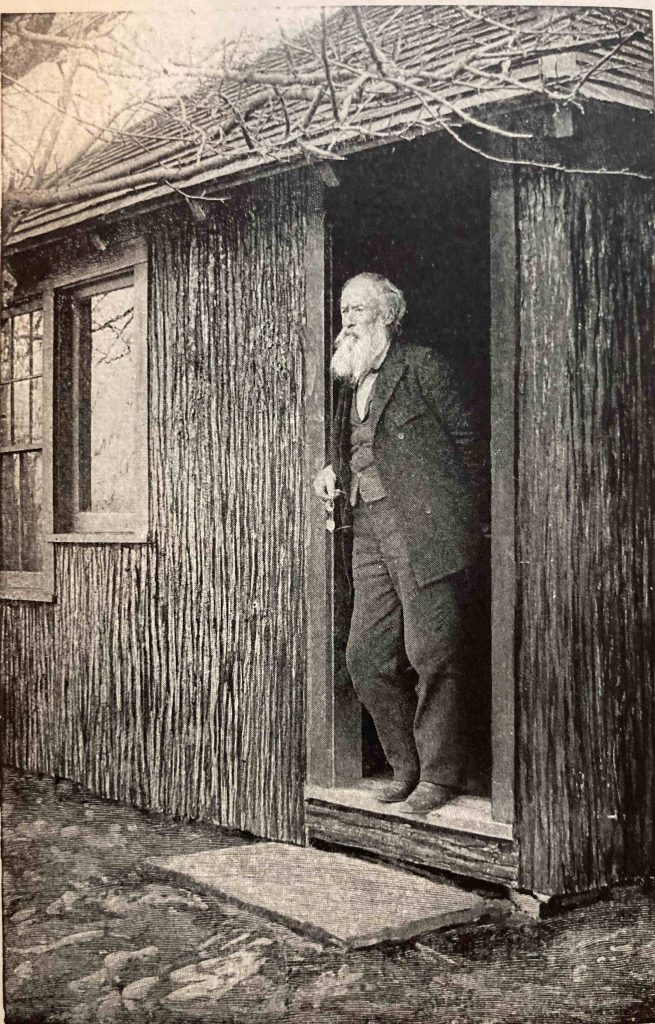

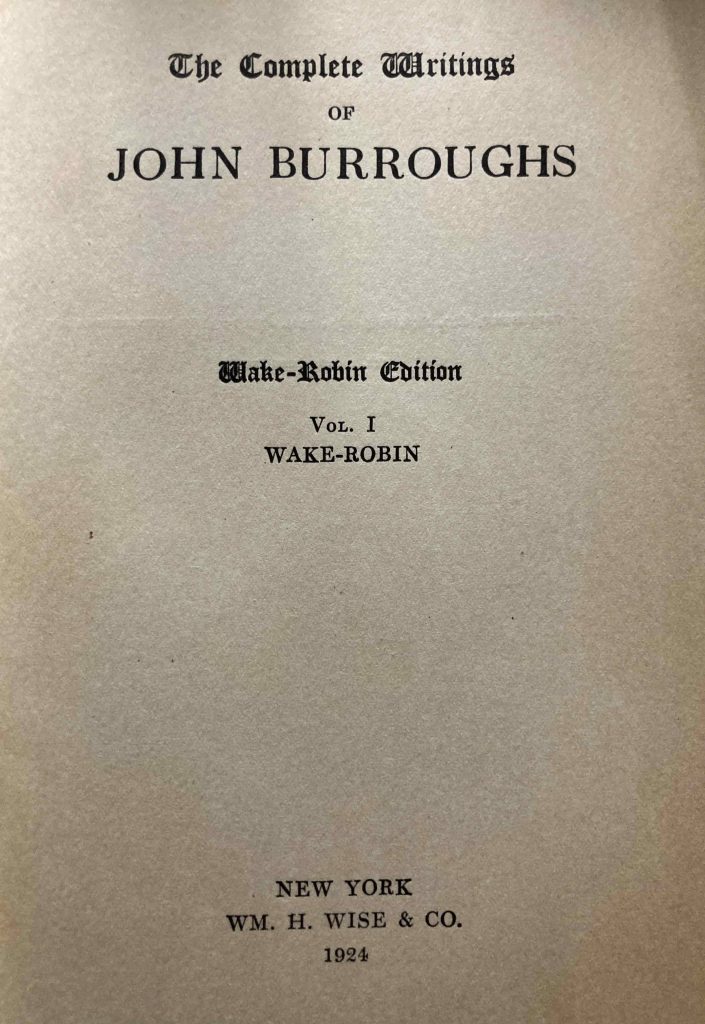

Why am I back reading Burroughs? After all, he is the second most well-known nature writer of his day (admittedly, a fairly distant second) after John Muir. Many of his books are still in print, and an annual nature-writing medal bears his name. However, the more I delve into the nature-writing world of the 1860s through the 1920s (after which it virtually disappears for a couple of decades), the more I come to realize that Burroughs was its High Priest. His name is the one most mentioned by other nature writers, either well-known in their day or utterly obscure then and now. He set the tone for the time; to understand many of the nature books that followed and the Nature Movement (as Dallas Lore Sharpe calls it) of which they were a part, it is vital to come to grips with Burroughs, including his style, subject matter, and outlook. A few essays will not suffice. I have invested (money and time) in getting to know him well, through all twenty-three volumes of his Collected Works, published three years after his death in the “Wake-Robin Edition”. I was fortunate enough to locate a copy of the set in excellent condition for a third of the price (converted to 2022 dollars) that the set would have cost new. In one volume, I noticed a few pencil marks; otherwise, there is no writing in any of the volumes, no sign of ownership whatsoever. The bindings are tight, the covers undamaged. The pages are a bit tanned, but still of a paper quality sufficient to have deckled sides and a gilt top edge. The cover is supposedly a very dark green, though closer to black. On my bookshelf, the volumes comprise a two-foot dark wall awaiting me. I suspect it will be many years before I reach its end.

Meanwhile, from time to time, I will pull the next volume down from the shelf and saunter through it. It will help keep me reminded of Burroughs’ centrality to nature-writing between shortly after the passing of Thoreau and his own death in 1921. Why he played such a leading role in the Nature Movement is a question that will take much pondering to answer; however, I will sketch out an initial explanation in my next blog post. In this first volume of his work, I encounter a young(ish) John Burroughs in his mid-thirties. According to the dates at the ends of each essay in the book, though, its contents date from 1863 through 1869, when he was in his 20s. In keeping with the day, Burroughs included in his outdoor experiences both hunting and fishing. It was perfectly reasonable to shoot a bird in order to identify it or to describe a trout that had been caught and eaten. At times it is tempting to be deeply troubled by this; then I recall that I am at the beginning of Burroughs’ 50-year journey as a writer, during which his outlook toward nature certainly changed.

The essays in this volume can be dispatched in relatively short order. His opening salvos in the nature field definitely emphasize birds; as he notes in the preface, he wishes the book to be “an invitation to the study of Ornithology.” As such, it is one I must turn down. Most of the essays are highly bird-centric, with the notable exception of “Birch Browsings”, a whimsical account of a nature excursion (with the aim of trout fishing) that Burroughs undertook with some friends. The trip was mostly a disaster, since the fishing party was unable to figure out the directions to the lake, and ended up somewhat lost in the woods with practically no food. Along the way, Burroughs describes some of the flora and fauna. The essay is a delightful mix of story and nature experience and is frequently anthologized.

Throughout the essays, I paid close attention to any name-dropping, seeking to identify Burroughs’ early influences. He mentioned Thoreau repeatedly, and Wilson Flagg once. He quoted Wordsworth but did not mention Emerson. In the more strictly ornithological realm, he mentioned John James Audubon, Thomas Nuttall, and Alexander Wilson; twice he referred to a “Dr. Brewer”. I was surprised to locate Thomas Mayo Brewer (1814-1880) right away using Google.

Those looking for early glimmers of a conservation outlook will not find them here. In fact, in his very first essay, “The Return of the Birds,” Burroughs argues that human civilization has been highly beneficial to many American bird species. Many songbirds, he suggested, are more abundant and sing more now that they have meadows and forests created by European settlers clearing the forest. (The recognition that Native American peoples intentionally cleared forest areas using fire long before the arrival of the Mayflower would have to wait on William Cronon 132 years later.) Here is Burroughs’ argument, in full:

Yet, notwithstanding that birds have come to look upon man as their natural enemy, there can be little doubt that civilization is on the whole favorable to their increase and perpetuity, especially to the smaller species. With man come flies and moths, and insects of all kinds in greater abundance; new plants and weeds are introduced, and, with the clearing up of the country, are sowed broadcast over the land.

As noted earlier in this post, this is a snapshot of John Burroughs in his early days as a writer; I am eager to see how his views may change across half a century of his work. It is unlikely that he realized when he first issued his invitation to others to get out into nature and study the birds that he was at the inception of a Nature Movement that would span the rest of his life, and in which he would take considerable part.