As the tendency of mankind to crowd into towns grows stronger, the joys of country life and the workings of Nature are more and more excluded from the daily experience of humanity. In a few the primal love of the wild is too strong for suppression, and turning from the hot and noisy streets they find it a refreshment of spirit to meet our little brothers of earth and air in the wider spaces of their own territory.

IN A WORK EVOCATIVE OF MARY TREAT’S ESSAYS, THE PECKHAMS SET OUT, IN THIS VOLUME, TO SHARE THEIR RESEARCH INTO THE BEHAVIOR OF SOLITARY AND SOCIAL WASPS. The result, like that of Mary Treat’s own essays, is a book that both impressed me for the painstaking observations of the authors (spending days in midsummer watching a single insect) and eventually numbed me somewhat with all of the data provided. It seems the Peckhams watched hundreds of wasps belonging to dozens of species as they all went about their daily routines, most involving building nesting chambers, paralyzing or killing prey species (caterpillars, grasshoppers, spiders, and others), and bringing the prey back to the nests for the young larvae to feed upon. (Ironically, despite the opening reference to “little brothers”, nearly all the Peckham’s studies focused on the females of their species.) Nowadays, research into the behaviors of individuals would be agglomerated and presented that way to the reader; but in this book, one is regaled with a myriad of life stories of wasps, some intelligent, some daring, some shy, and some clumsy. Writing about the mud dauber wasps, for example, the Peckhams remark:

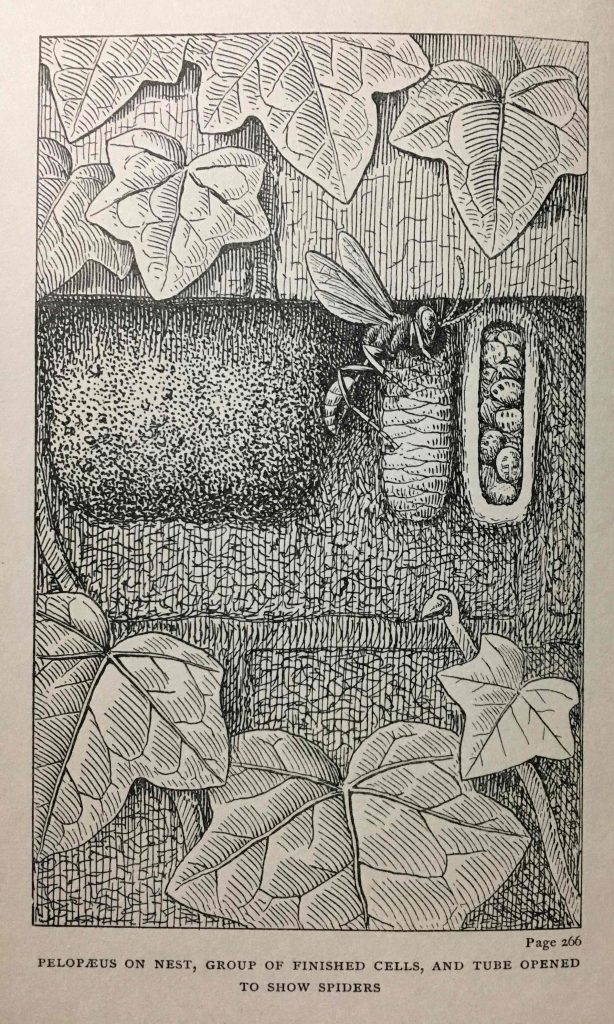

All animated by the same compelling instinct, they are still individuals, and the character of each enters into her work. One picks up the first spider she sees, no matter how tiny it may be, and makes twenty-five or thirty journeys before her cell is filled, while another seems to have a calculating term of mind, using four or five big spiders instead of a quantity of small ones. Has she made a note of the calibre of her cell, and determined to save herself trouble by looking farther and selecting the largest ones that will go in?

AND HERE, THE FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION OF THE BOOK REVEALS ITSELF. As echoed by the title of the book’s final essay, Instinct and Intelligence, the book sets out to answer whether members of a species all behave identically (evidence for instinct at work) or uniquely (evidence for varying degrees of intelligence). As a legacy of Rene Descartes, animals were assumed to be the equivalents of machines, acting entirely by instinct What the Peckhams and other naturalists revealed at the time is a very different story. To do this, however, necessitates trying to see the world through a wasp’s eyes, in a form of “wasp psychology”:

The necessity of interpreting the actions of animals in terms of our own consciousness must be always with us. To interpret them at all we must consider what our own mental states would be under similar circumstances, our safeguard being to keep always before us the progressive weakening of the evidence as we apply it to animals whose structure is less and less like our own.

Here is one such interpretation, a short story with a wasp as protagonist:

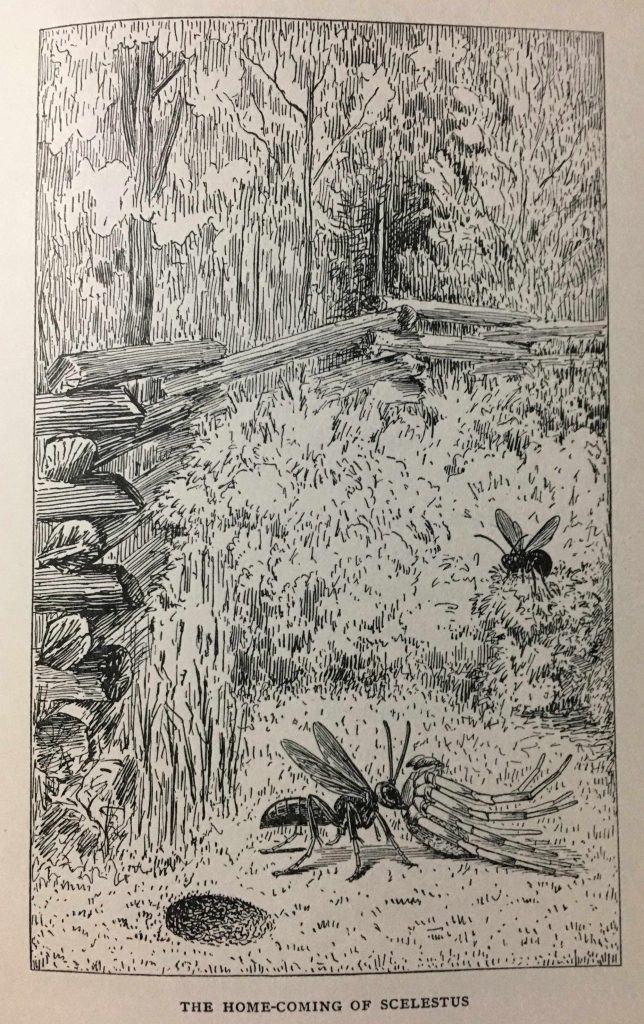

When we went to the garden at eight o’clock on the following morning…, [Pompilus] scelestus was still sound asleep in her leafy bower. We thought it best to awaken her, for a large spider had spread its web just below, and if the wasp should drop upon it nothing could save her. We therefore aroused her gently, whereupon she crept slowly up the stem and, taking her stand on the highest point, surveyed the world. Then, after stretching herself sleepily, she made her toilet, cleaning off her wings and legs, and washing her face with her feet like a cat. When these duties were finished she walked slowly about for an hour, visiting her nest every now and then. Suddenly, at half past nine o’clock, her whole manner changed, and seeming very much excited she ran rapidly along, parallel with the fence, for fifteen or twenty feet and then, rising on her wings, flew far away into the woods. She had evidently gone hunting at last, and we watched eagerly for her return. She was not successful at once, however, for at half past ten she came back without anything, stayed at the nest for a few minutes, and then flew to the woods again with the same excited manner as before. Perhaps she had already caught her spider at some far distant spot, and was getting her bearings preparatory to bringing it home; but it was half past one when she suddenly appeared, five or six inches from the next, coming back through the fence, and dragging a large Lycosid [spider]. This she laid down close by, and began to bite at the legs…. Her movements were full of nervous excitement, in marked contrast to those of the previous day. Presently she went to look at her nest, and seemed to be struck with a thought that had already occurred to us — that it was decidedly too small to hold the spider. Back she went for another survey of her bulky victim, measured it with her eye, without touching it, drew her conclusions, and at once returned to the nest and began to make it larger….

THE RESULT IS A REMARKABLY DIFFERENT PORTRAIT OF THE LIFE OF A WASP THAN WHAT MOST OF US IMAGINE. Living in an age when invertebrates have been “othered” to the point that they seem akin to aliens, I found this account almost jarring. Consider the human characteristics this wasp exhibits, from her lazy morning stretch upon waking up to her careful problem-solving of the puzzle of the small nest hole and large spider. Through the Peckhams’ eyes, the wasps are another culture, yes, but one that merits our respect. Granted, at other moments the Peckhams behave more like conventional field scientists, digging up nest burrows to view their occupants or altering the landscape around a ground nest to see how a wasp responds to the changes. Somewhat comically, the scientists also express an awareness of the harm their research is causing some of the wasps:

We had not supposed that the digging up of her nest would much disturb our Sphex, since her connection with it was nearly at an end; but in this we were mistaken. When we returned to the garden about half an hour after we had done the deed, we heard her loud and anxious humming from a distance. She was searching far and wide for her treasure house, returning every few minutes to the same spot, although the upturned earth had entirely changed its appearance. She seemed unable to believe her eyes, and her persistent refusal to accept the fact that her nest had been destroyed was pathetic. She lingered about the garden all through the day, and made so many visits to us, getting under our umbrellas and thrusting her tremendous personality into our very faces, that we wondered if she were trying to question us as to the whereabouts of her property. Later we learned that we had wronged her more deeply than we knew. Had we not interfered she would have excavated several cells to the side of the main tunnel, storing a grasshopper in each. Who knows, but perhaps our Golden Digger, standing among the ruins of her home, or peering under our umbrella, said to herself: “Men are poor things: I don’t know why the world thinks so much of them.”

THAT LAST THOUGHT MAKES A SPLENDID CLOSURE TO THIS POST. In the end, I found this book highly captivating at first, though rather repetitive after the first few dozen pages, as the Peckhams shifted from one genus of wasp to another one. (Clearly the Peckhams were patient and highly devoted to their research subjects). From the standpoint of 2020, 115 years on, the authors led me into a truly foreign world — a quite different perception of wasps and their natures than what most of us have today. I also noticed the sheer number, and variety, of wasps the Peckhams encountered on a bit of rural land outside Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Sadly, I suspect that repeating her project in the Eastern United States nowadays would be far more difficult. So many of our insects have been reduced dramatically in number. This book helps me see how much of a tragedy that loss really is — the diminution of other societies of beings, with their thoughts and plans and lives to lead.

BEFORE CLOSING, I OUGHT TO REMARK ON TWO OTHER FIGURES THAT ARE ASSOCIATED WITH THIS BOOK. The first is James Henry Emerton, the illustrator. His drawings are, in my humble opinion, stunning, though I will leave a more in-depth critique to others. According to Wikipedia, Emerton (1847-1931) was an arachnologist in addition to being an illustrator (and watercolor artist), who spent most of his life in Massachusetts. His magnum opus was Common Spiders of the United States, which was reprinted by Dover Books in 1961 with a sufficiently garish cover that I feel compelled to reproduce it below. The image is accompanied by a somewhat blurry image of Emerton himself, who probably would also have disapproved of the cover, or being associated with it in this way.

THE SECOND PERSON I NEED TO MENTION IS NONE OTHER THAN THE SAGE OF SLABSLIDES, JOHN BURROUGHS. Burroughs wrote an introduction to the book, no doubt contributing markedly to its sales in the process. He heaped considerable praise on the work, noting that

It is a wonderful world of patient, exact, and loving observation, which has all the interest of a romance. It opens up a world of Lilliput right at our feet, wherein the little people amuse and delight us with their curious human foibles and whimsicalities, and surprise us with their intelligence and individuality. Here I had been saying in print that I looked upon insects as perfect automata, and all of the same class as nearly alike as the leaves of the trees or the sands upon the beach. I had not reckoned with the Peckhams and their solitary wasps. The solitary ways of these insects seem to bring out their individual traits, and they differ one from another, more than any other wild creatures known to me….

I am free to confess that I have had more delight in reading this book than in reading any other nature book in a long time.

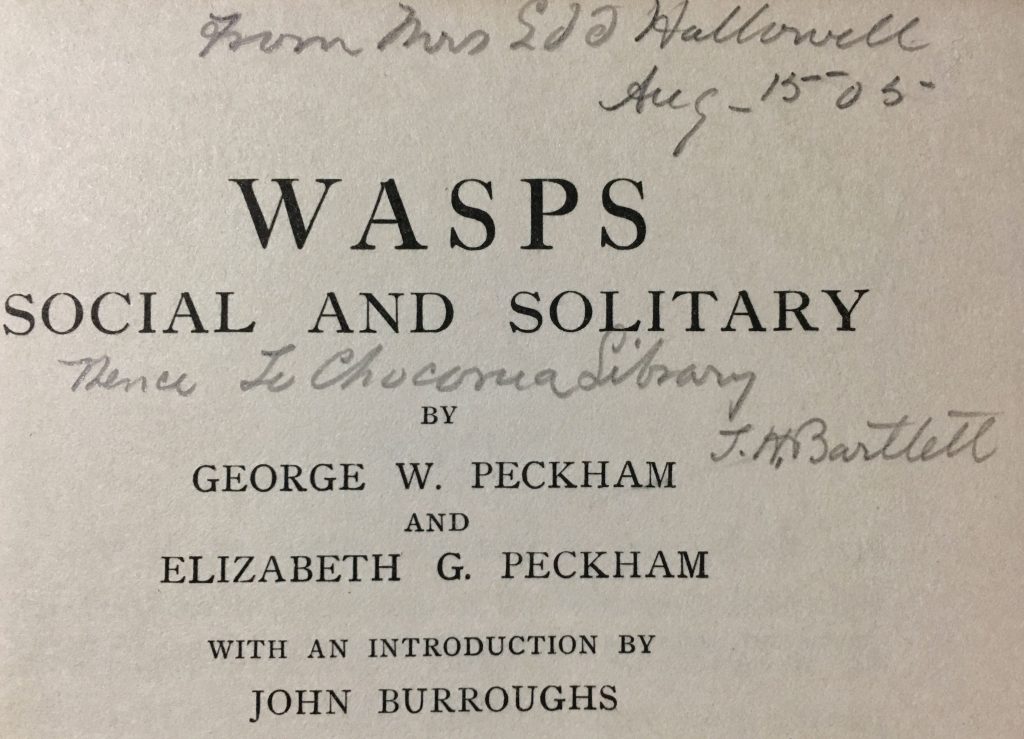

AT LAST, I HAVE QUITE A TALE TO TELL ABOUT THE JOURNEY MY COPY OF THIS BOOK HAS TAKEN. In fact, the book contains a nearly complete, and rather amazing, account of its journeys. In an amazing coincidence, this book comes from the homeland of another author from this time period — Frank Boles! First, I know that the book was published in 1905, and sold by W. B. Clarke Co. Booksellers. The purchaser identifies herself as Mrs. Edd Hallowell, who then gave the book to someone else (probably J.H. Bartlett) on August 15th, 1905. Some time after that, it passed “thence to the Chocorua Library”, a gift of J.H. Bartlett. Chocorua Library, in Chocorua, New Hampshire, is situated just a short distance south of Lake Chocorua and the summer country home of Frank Coles. It was volume number 2260 in the humble and nondescript Chocorua Public Library building, where it spent its days until quite recently. According to the stamp date on the back library card pocket, it was last due July 31st 2003. Soon after that, I assume that it was sold at a library book sale (one of those treats of northern New England summer weekends) and probably purchased there by Robert Purmort Books, Newport, New Hampshire, which sold the copy to me via ABE Books on 26 July of this year.