According to Wikipedia (the font of all knowledge), Horace Lunt was a linguist in Slavic Studies who lived from 1918 until 2010. Unfortunately, that does not explain how he managed to publish a book of New Hampshire nature essays in 1888. Hence the problem. While trying to gain information about this author, every site I visited invariably led to the wrong Horace Lunt. Finally, I stumbled upon a scan of a book on the Lunt family of New England, which included a paragraph about the right Horace. What I learned only made him more mysterious to me. Horace was born on March 17, 1838. He worked as a house servant before joining a local militia company in 1861 and then a Maine infantry regiment a year and a half later. His regiment fought in many battles during the Civil War, including Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Wilderness, Cold Harbor, and Appomattox. He was one of the few members of his regiment to survive the war, although one of his legs was severely impaired due to the long marches and other hardships. After the war, he became a nature writer, publishing three books; Across Lots was the first. He died in 1911. I could not find an image of his grave, let alone of him.

So I fill in the blanks as best I can. What happened to him between 1865 and the publication of his first book? Did he try his hand at other careers along the way? Did he have the 19th Century equivalent of PTSD? (How could he have possibly endured so many horrific battles psychologically unscathed?) Did he perhaps seek solace in nature, a calming presence to soothe his troubled memories? I don’t know. I did notice the presence of his past, in terms of how frequently he would use military images to describe natural scenes in his essays. Here is how the first essay, “A March Ramble,” opens:

March, in New England, is the disputable month between the seasons spring and winter; the space, as it were, between the picket lines of both armies, where many battles are fought for the mastery and power of governing the land. Winter commands Boreas to station his wind batteries on the bleak northern hills to belch forth a storm of snow and hail, and a general frigid icicle charge is ordered along the whole line until not a vestige of spring is seen. Then the frost army, wearied with its fierce onslaught, sleeps, and the vernal force, driven far southward, turns again its face toward the foe, insidiously creeps along the flank, and takes the gray old general in his fancied stronghold by surprise… Winter wakes again and marshals his strength, but his front is not so vigorous. He sullenly retires before the genial commander of the other side, that moves slowly and steadily forward to the vernal equinox.

Equinox? Appomatox? They practically rhyme. Only, in this version of the story, the South ultimately wins (for the spring, at least).

I truly wanted to enjoy Lunt’s work. His essays are vivid, and his emulation of Thoreau is uncanny. He captures a couple of Thoreau’s mannerisms from his journals, including a tendency to interrupt description to declare something fervently and his frequent addition of questions without answers. However, he lavishes the most praise on John Burroughs, “whose writings have the true sylvan ring — to read them is next to walking in the woods.” And that, I suppose, is what Lunt is chiefly after in his book — using text to evoke a virtual reality through which the reader can travel, as if out of doors. Lunt keeps his own musings to a minimum and eschews references to literature and history. Reading his descriptive passages, I feel like I am there with him — roaming the woods, gazing down into a pond, following a half-tumbled-down wall. Consider this delightful passage on autumnal plants and how they disperse their seeds:

As I walk across-lots, I am struck with the varied and ingenious methods the different plants have used to scatter their seeds. Here is an army of goldenrods and asters, milk-weeds and epilobiums, holding aloft on their wand-like stems millions of seeds, to which are attached balloons, parachutes and wings, that the wind at the proper time may carry them miles away. I wave one of these wands when, as if by magic, hundreds of the winged grains go sailing through the air like the flight of insects. Here, too, are hooks, barbs, and prickles that cling to the dress of passers-by or to the hairs of cattle, and thus are carried away to be rubbed off and deposited in some other locality. Other seeds artfully hide themselves in lucious, brilliant wrappings that the birds may be attracted to them. Strawberries, raspberries, and the early drupes have scattered their seeds by this process; but the various cornels, honeysuckles, greenberries, rose and spice bushes, the bright red fruit clusters of the winter-berry, the purple panicles of the prim, that feast the eyes of the autumn rambler, are still waiting patiently for the snows to put an embargo on other supplies near the ground.

Here I chose a botanical passage. But Lunt’s observational skills were far-ranging. He emphasized birds the most (meticulously describing their color patterns, as if the poor reader could ever remember them in a book devoid of illustrations). But he also wrote about snakes, turtles, small mammals, insects, and even microscopic pond life. While his command of animal behavior was perhaps average for nature writers of the time, his skills in identifying and describing organisms were prodigious. And yet I struggled with feeling that the book was missing something vital — without which it simply could not stand alongside Thoreau. After reading one of the last passages from the final essay, “Cross-cut Views of Winter,” I finally figured it out.

I note the tracks of various prowlers in the woods. A rabbit has lately passed along, making indentations in the snow at regular intervals, as if he had been surveying or pacing off a certain portion of the lot for himself. Further on the lines appear more numerous; cross and re-cross each other, and are tangled in such a knot that it would be a hopeless task to find the creatures’ homes. They seem to have gone everywhere, and arrived at no particular place.

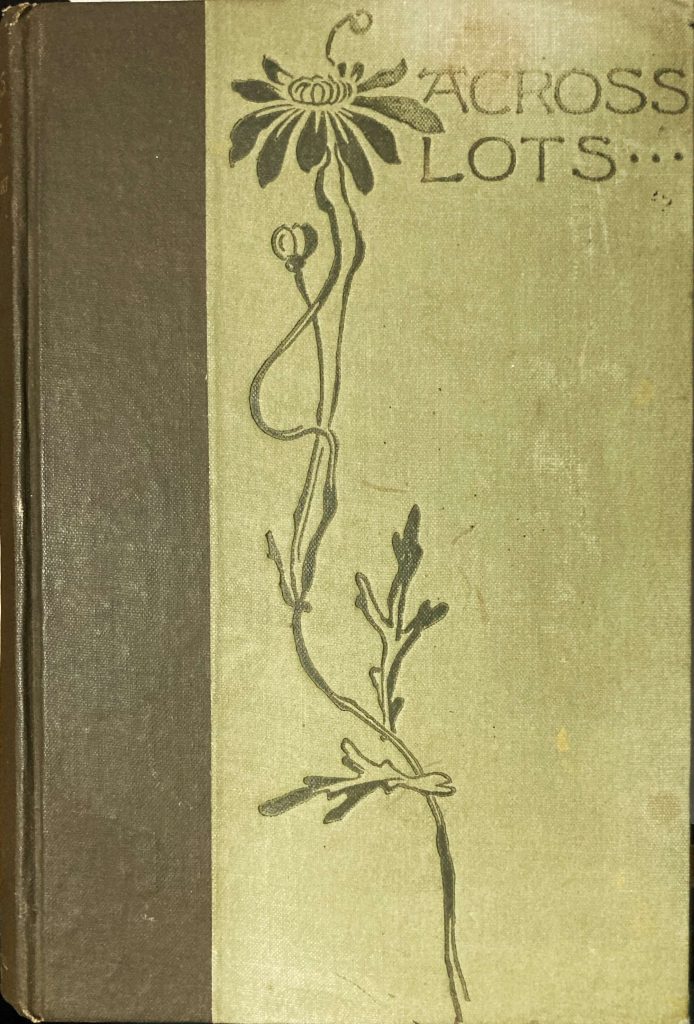

Thank you, Horace! That is precisely what I mean. Your book goes everywhere (within your New Hampshire woodland domain) and arrives at no particular place. There is no point to your essays — or rather, the point of your essays is the ramble itself. Unless I include your understandable fascination with war imagery, there are no connection to anything larger than the moment and the walk and the things you discover along the way. There is no destination. A reader could pick up the book and begin anywhere — could probably even read the paragraphs in backward order, and it wouldn’t matter. Across Lots is intended as a vehicle for virtual experience at a time long before the coffee-table photography book, video, and virtual reality headsets. And as such, it can end equally at any point, such as here.