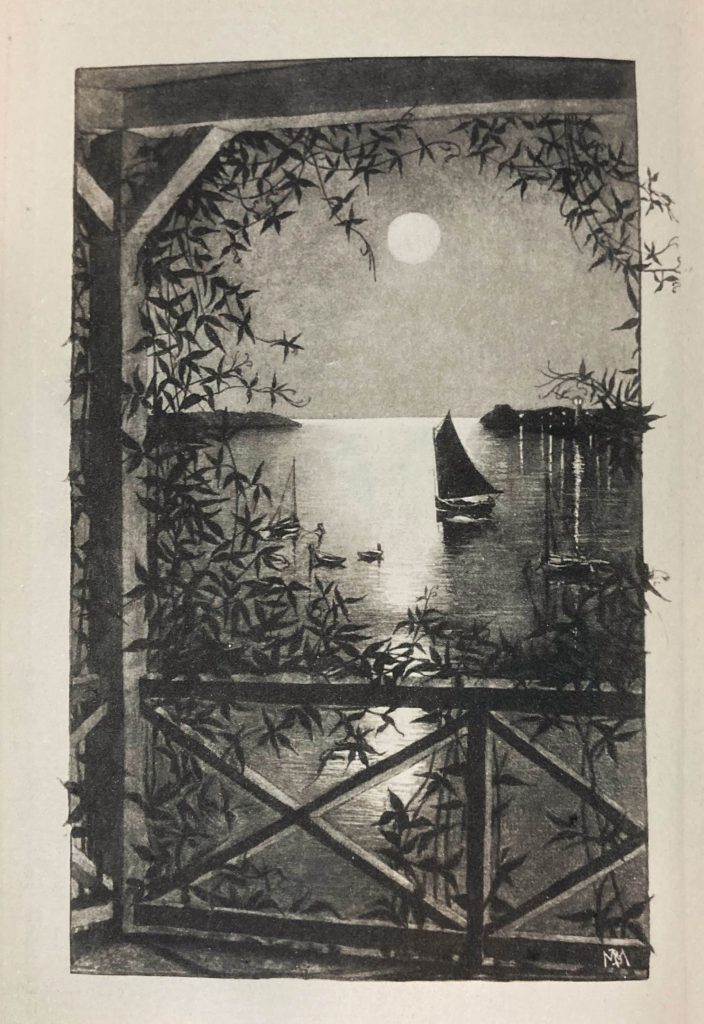

There is virtually no structure to this volume by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, unless you consider the frontispiece. That image depicts a moonglade, the path made by moonlight on the water. The term was first used by James Russell Lowell in the mid-1800s and commandeered by Higginson for an essay of the same name some years later. The Prefatory Note to this work teasingly remarks, “It may interest some readers to know that the designer of the frontispiece to this volume is identical with the child described in its closing pages.” (It also notes that the view in the frontispiece is in Newport, Rhode Island.) And thus, this image and its accompanying essay bookend the text. But who is the mysterious artist? Higginson only identifies her as “this little maiden who sits beside me in the shadow.” Fortunately, she placed her initials on the work; unfortunately, “MBM” has proven elusive. There was a writer of children’s fiction, Mary Bertha Toland, née MacKenzie (1825?-1875), but she would have been too close in age to Higginson to have been a child at the time he originally wrote the essay.

“Moonglade” is evocative of the esthetics of Ruskin mingled with a touch of Transcendentalism; as such, it makes as good a place as any for approaching this slender volume. Higginson opens the essay by remarking that “There is no Americanism more graceful than the word ‘moonglade.’ Later, he observes,

So calm are sometimes the summer evenings by this bay that all motion sees at an end, and the weary play of events to have stopped forever. But Nature never really rests, and the moon, which seems only an ornament for this quiet water, is in reality leading it along with restless progress, bidding it roll lazily over reefs, surge into sea caves, and sweep away with it any boat that is not moored.

This notion of nature as constant flux is a fine candidate for a theme of many of these essays, beginning with “The Procession of the Flowers.” As advertised, that essay considers the progression of blooms from spring until autumn in New England (more precisely, Worcester, Massachusetts, where Higginson served as minister of the Worcester Free Church). In a later essay on“April Days“, Higginson writes about how many flowering plants native to the Boston region have been displaced by human development. The result is an abundance of naturalized plants, including dandelion, buttercup, chickweed, celandine, mullein, burdock, and yarrow, among others. “Bigelow’s delightful book Florula Bostoniensis,” he keenly observes, “is becoming a series of epitaphs.” The result is two contrasting forms of change: Nature’s change across the seasons (always happening, but consistent year to year), and the landscape changes of Massachusetts (urbanization and suburbanization) with their radical impact on the local flora — and “the special insects who haunt them.” Do I detect a hint of woe in Higginson’s observation (quoting a letter from Dr. Thaddeus William Harris) that so many native plants have “disappeared from their former haunts, driven away, or exterminated perhaps, by the changes effected therein”? I cannot help but read Higginson in the light of the ongoing modern-day global climate disruption, where even the reliable progression of the flowers is being considerably impacted. “Fair is foul, foul is fair,” three witches once remarked.

Another theme in several pieces in this volume is the human need for Nature. Here, Higginson seems to presage recent research into the role of nature experiences in child development (including the intellect):

No man can measure what a single hour with Nature may have contributed to the moulding of his mind. The influence is self-renewing, and if for a long time it baffles expression by reason of its fineness, so much the better in the end.

The soul is like a musical instrument; it is not enough that it be framed for the most delicate vibration, but it must vibrate long and often before the fibres grow mellow to the finest waves of sympathy. I perceive that in the veery’s carolling, the clover’s scent, the glistening of the water, the waving wings of butterflies, the sunset tints, the floating clouds, there are attainable infinitely more subtile modulations of thought than I can yet reach the sensibility to discriminate, much less describe.

Cue applause from Ralph Waldo Emerson in the shadows.

Spending time in nature, Higginson argues, ought to be a vital part of healthy education for children. “The little I have gained from colleges and libraries,” he declares, “has certainly not worn as well as the little I learned in childhood of the habits of plant, bird, and insect.” Alas, schools at the time (and now) generally did not (do not) offer those opportunities to young people. “Under the present educational system we need grammars and languages far less than a more thorough out-door experience.”

By way of a miscellany (which reflects this book well), another thing I particularly noticed while reading it was the natural philosophy and science community in which HIgginson lived and wrote. At various points in the book, he quotes Humboldt; he refers to “so good an observer as Wilson Flagg”; he quotes Dr. Thaddeus William Harris, American entymologist; and he mentions Ralph Waldo Emerson. His greatest praise is reserved for Thoreau: “Thoreau camps down by Walden Pond, and show us that absolutely nothing in nature has every yet been described, — not a bird nor a berry of the woods, not a drop of water, nor a spicula of ice, nor summer, nor winter, nor sun, nor star.” Later, he refers to a conversation with Thoreau about local bird distributions in December, 1861, just five months before he died: “…he mentioned most remarkable facts in that department, which had fallen under his unerring eyes.”

Following my encounters with the Collector in Wild Honey by Samuel Scoville, Jr., I was refreshed to discover in Higginson a strong resistance to violence against birds. I think it is in keeping with his radical abolitionist spirit (he was one of Secret Six that backed John Brown’s Raid) and strong moral principles regarding freedom and basic rights for all that he extends similar care to the birds:

The small number of birds yet present in early April gives a better opportunity for careful study, — more especially if one goes armed with the best of fowling-pieces, a small spy-glass; the best, — since how valuable for purposes of observation is the bleeding, gasping, dying body, compared with the fresh and living creature, as it tilts, trembles, and warbles on the branch before you!

Before I close my book and place it next to all the others collecting in my bookshelf of completed texts, I offer up this lovely descriptive passage as evidence of the soaring, elegant prose Higginson sometimes achieved:

As I sat in my boat, one sunny afternoon of last September, beneath the shady western shore of our quiet lake, with the low sunset striking almost level across the wooded banks, it seemed as if the last hoarded drops of summer’s sweetness were being poured over all the world. The air was full of quiet sounds. Turtles rustled beside the brink and slithered into the water, — cows plashed in the shallows, — fishes leaped from the placid depths, — a squirrel sobbed and fretted on a neighboring stump, — a katydid across the lake maintained its hard, dry croak, — the crickets chirped pertinaciously, but with little, fatigued pauses, as if glad that their work was almost done, — the grasshoppers kept up their continual chant, which seemed thoroughly melted and amalgamated into the summer, as if it would go on indefinitely, though the body of the little creature were dried into dust. All this time the birds were silent and invisible, as if they would take no more part in the symphony of the year. Then, seemingly by preconcerted signal, they joined in: Crows cawed anxiously afar; Jays screamed in the woods; a Partridge clucked to its brood, like the gurgle of water from a bottle; a Kingfisher wound his rattle, more briefly than in spring, as if we now knew all about it and the merest hint ought to suffice; a Fish-Hawk flapped into the water, with a great, rude splash, and then flew heavily away; a flock of Wild Ducks went southward overhead, and a smaller party returned beneath them, flying low and anxiously, as if to pick up some lost baggage; and, at last, a Loon laughted loud from behind a distant island, and it was pleasant to people these woods and waters with that wild shouting, linking them with Katahdin Lake and Amperzand.

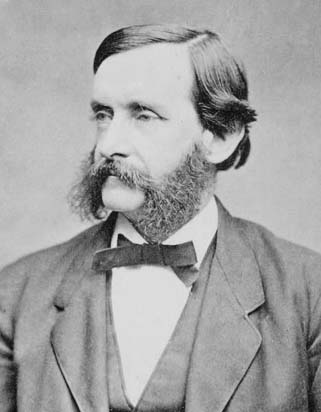

Next, a few words about Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823-1911) and my copy of his book. According to Wikipedia, Higginson was a Unitarian minister, author, abolitionist, and soldier. During the Civil War, he served as Colonel of the first federally recognized black regiment. He was a correspondent and mentor to Emily Dickinson (1830-1886). His own books covered a range of topics, from his Civil War experiences to the rights of women. HIs few nature essays originally appeared in Outdoor Papers, published in 1889. In 1897, he extracted most of the nature essays, combining them with “Moonglade” to produce the present volume.

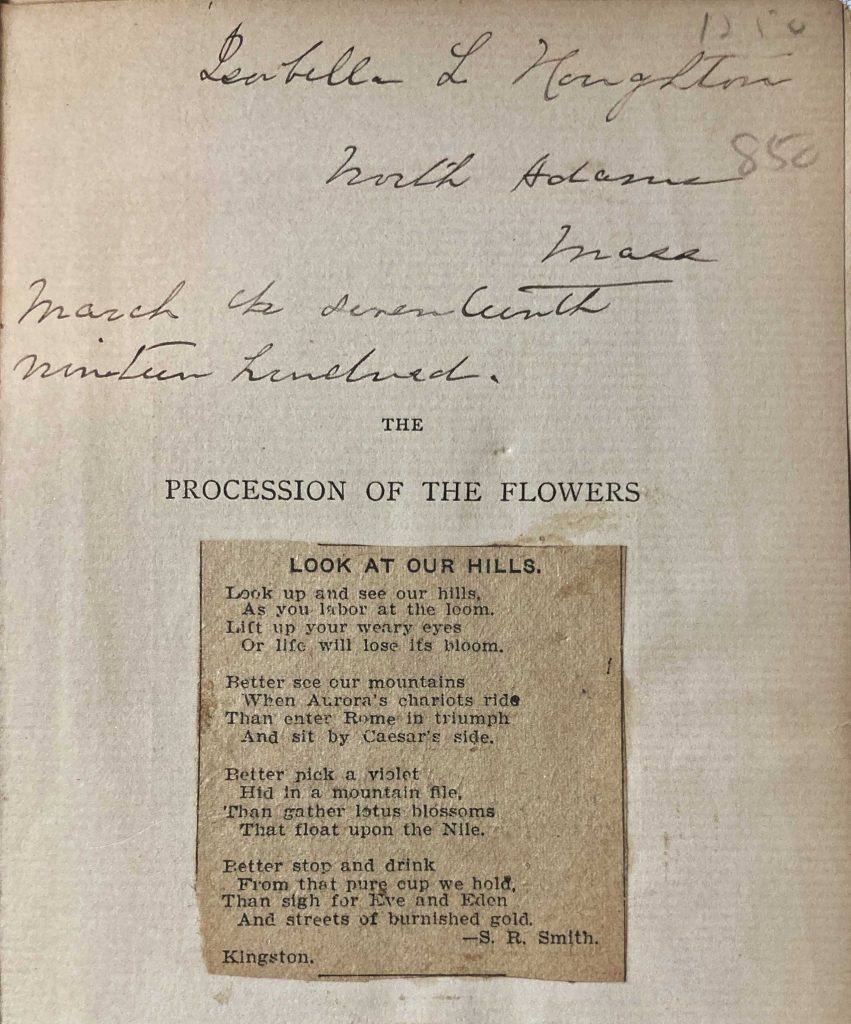

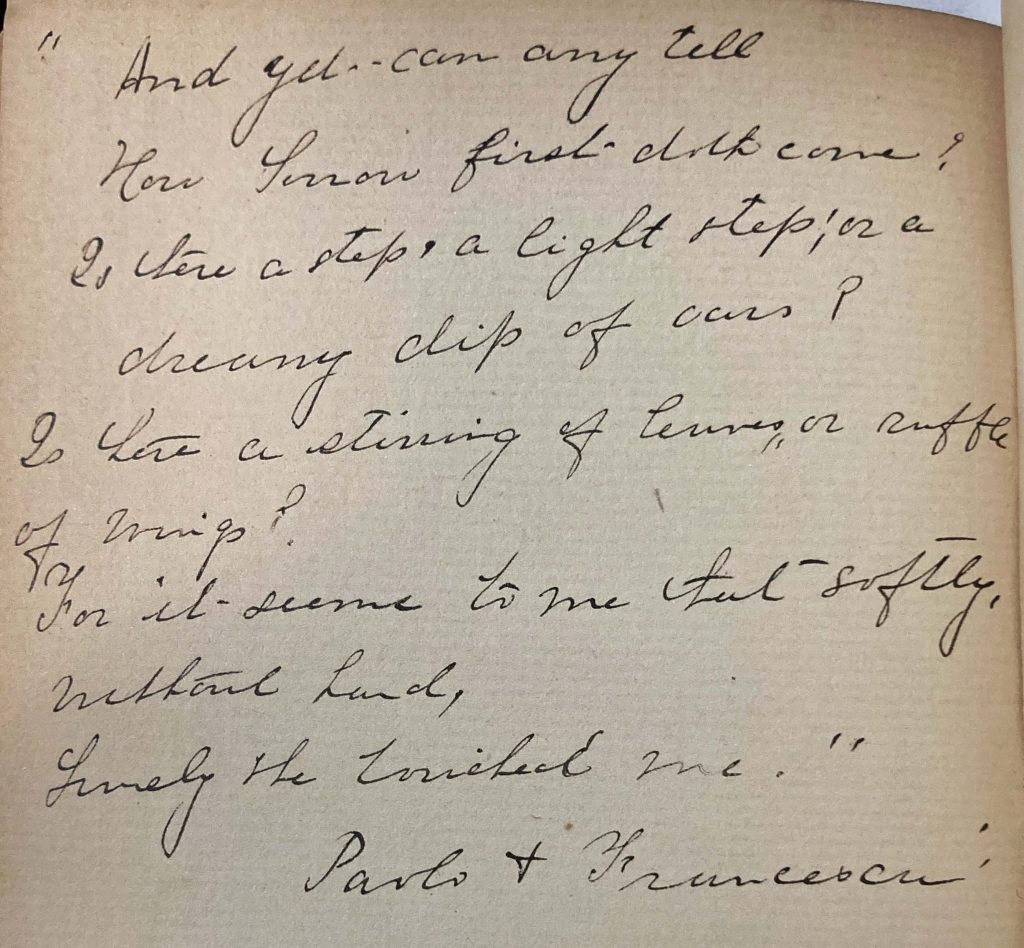

According to a signature inside the book, my copy was previously owned by Isabella L. Houghton of North Adams, Massachusetts; she obtained the book on March 17, 1900. The only thing I was able to learn about her online is that she also signed her name in a copy of Women and the Alphabet: A Series of Essays, also by Higginson, published in 1900. I assume that she passed the newspaper clipping with a poem by S.R. Smith of Kingston in the front. For the curious, S.R. Smith happens to be the name of the world’s leading manufacturer of pool deck equipment. Enough said. The back page of the book contains a passage from Paolo and Francesca that appears to have been copied in Isabella’s hand. The work was a tragedy in four acts (first performed in 1902) by the English poet and dramatist Steven Phillips (1864-1915). The particular copied bit was spoken by Franc (frankly?); the copyist took a bit of liberty with the first line. Here is the original:

And yet, Nita, and yet — can any tell

How sorrow forth doth come? Is there a step,

A light step, or a dreamy drip of oars?

Is there a stirring of leaves, or ruffle of wings?

For it seems to me that softly, without hand,

She touches me.