I have read nearly 50 “nature books” for this blog (with easily close to 100 to go), spanning the eighty years from 1861 to 1941. Yet this is the first time I can say that, while this work scarcely reads like a novel, it has an antagonist known as The Collector. While not present in every essay, he dominates the scene and dictates the “nefarious calling” that all other outing members, including the author, participate in: egg collecting, a.k.a., nest robbing. A host of other archetypal characters play bit roles in the drama: the Banker, the Naturalist, the Ornithologist, the Botanist, and the Native. Since Scoville does not elect to assign himself a persona, I will call him the Author. These lesser characters are enablers of the wanton destruction that repeatedly happens throughout this book’s pages. Indeed, the Author reports with pride his many successful ventures at locating birds’ nests to be plundered for the Collector’s collections. He even remarks at one point on how

some of the happiest days of my life have been spent with collectors of birds’ eggs — oölogists, they call themselves. They are all so eager and excited and happy over their hobby that it is a pleasure to be with them. They regard me rather pityingly, however, because I take no share of the findings; yet I think that I have chosen the better part. Boxes of blown eggs leave me cold, but I shall never forget the days and nights in the wilderness which I have had on bird-trips, and the excitement of discovering rare nests and the pleasure of learning secrets of bird life, unknown to me before.

And the Collector does not select one egg from each nest; he takes them all. On one outing to a New Jersey marsh, the Author discovers the first pileated woodpecker nest in the state. Despite its apparent rarity, “urged on by the Collector,” the Author attempts to rob it — without success, I am grateful to report. And when out of the Collector’s company — as in several other essays in the book — the Author generally behaves with greater reverence toward most animals. He does approach venomous snakes with repugnance, however. Pointing out a “very real menace” rattlesnakes supposedly posed to humans, he proposed that big game hunters capture them all for “various zoölogical gardens.” (Lest he appears to be advocating a live capture solution, however, it should be noted that the skins of at least two timber rattlesnakes dispatched by the Author hung on the walls of his cabin in the New Jersey Pine Barrens.)

Venting over. Beyond the domain of the Collector, there is some delightful descriptive prose in this book. He mentions John Burroughs several times, though he does not identify any other nature writers or scientists of the day. (The Naturalist and the Ornithologist and the Botanist are never named.) For his faults, the Author is a skilled ornithologist and botanist who also takes a keen interest in how many landscapes of the Eastern US are haunted by traces of the human past. An old track through the pines was once a busy road for glassmakers and ironmakers in the Pine Barrens, while an old mill site in Connecticut once hummed with industrial activity. In recognizing stories in the landscape, he ties natural history into human history in a way that few other writers of his day did.

While there is no lofty poetry here, no sweeping metaphors or cosmic sentiments, there are still passages like this one describing an encounter with a bluebird:

Once, among all these interesting strangers, we heard the “far-away, far-away” of a bluebird — those lovely contralto notes which fall from the sky like drops of molten silver. Looking up, we saw that dear, brave bird of the North flying toward the sunset with the sky color on his back and the color of the red clay of the South on his breast, and we watched him until he was lost in a mother-of-pearl cloud.

Here, he describes the sounds of the night at his cabin in the Pine Barrens:

The shadows of the waving trees made a fretted, magical pattern on the smooth surface of the water. A pine-barren pickerel frog, all emerald and gold and purple-black, snored, and some other frogs unknown to me gave a couple of loud, startling notes which sounded like the clapping of two boards together. Then suddenly, in the distance, the stressed, hurried notes of a whippoorwill pealed through the darkness, to be answered by one close to the cabin. Over and over and over again these birds of the night repeated their triple notes with a little click after each one, hurrying as if they feared to be interrupted before they could finish. As the wild, sweet melody thrilled through the darkness, it seemed to me as if the moonlight itself had been set to music.

I will close my review of Wild Honey with this lovely passage describing a December boat journey into Okefenokee Swamp:

In the ice-blue sky the moon showed in the afternoon light like a bowl of alabaster, fretted and carved in shadowy patterns. In front of me stretched a fourteen-mile canal. The wine-brown water reflected the deep green of the long-leaf pines on either side of the stream, with now and then gleams of dragon’s blood and carmine-lake as the leaves of the black and sweet gums stained by the frost reflected their clors in the water. Everywhere were towering cypresses silvered with festoons of Spanish moss. Above the setting sun the western sky was a sea of amber and dim gold with shoals of violet and heliotrope clouds in its depths.

A few words about Samuel Scoville, Jr. (1872-1950) and my book copy are in order. Above is a photograph of the Author, circa 1918. According to his terse Wikipedia entry, Scoville was an American writer, naturalist, and lawyer. From Wild Honey, I can gather a few details; he resided in Haverford, Pennsylvania at the time of this book and worked on the thirteenth floor of an office building in Philadelphia. His practice was apparently lucrative; he also owned a home in Cornwall, Connecticut; a cabin (“Faraway”) in the New Jersey Pine Barrens; and a small peninsula on the coast of Maine. He married Katharine Gallaudet Trumbull in Philadelphia and had four children (all boys). He wrote a dozen books, mostly for children and mostly about nature. Wild Honey appears to have been his last collection of nature essays, though clearly with an adult audience in mind.

By 1929, the golden age of the artistic book cover had ended. My volume (the first and only edition) looks like most hardcovers of today, with textured board instead of cloth. The front cover is blank save for a small image impressed into the center, pictured above. What Poseidon and his trident have to do with this book is a mystery. The closest connection I can find is that the guides on his excursions into Okefenokee Swamp all used a “three-pronged push poll peculiar to the Swamp” to navigate the boat through the various waterways and hidden channels in the depths of Okefenokee.

I have to wonder how well this book was received. Its timing was far from ideal. It was published in October of 1929; at the end of that month came the great Stock Market Crash. I wonder how many Americans were looking to buy a nature book then? Furthermore, the Nature Movement, as described by Dallas Lore Sharp, was well over by then; World War I and the passing of John Burroughs in 1921 marked its close.

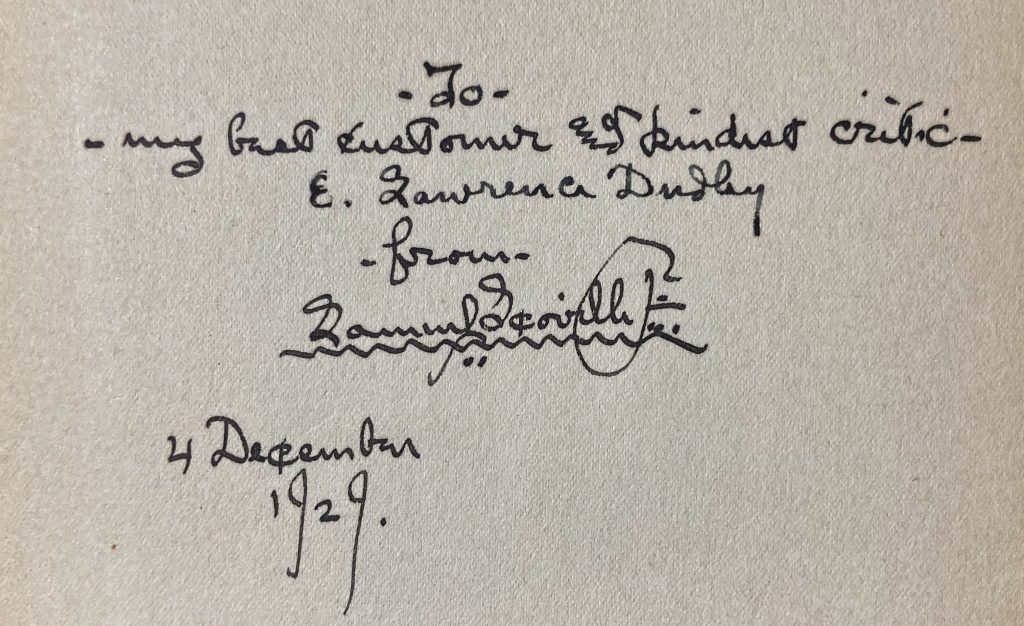

The Author inscribed my particular copy of Wild Honey to “my best customer and kindest critic” E. Lawrence Dudley on December 4th, 1929. Dudley (1879-1947) was the author of at least five works of biography and fiction, one of which was turned into a movie (Voltaire, 1933).