In the forest, the sunlight softly stealing through the half-grown leaves gilds the dark mosses, warms the cold lichens, kisses the purple orchids, makes glad the gloomiest crannies of the wood. Scarcely a cave so dark, or ravine so deep, but the light reaches to its uttermost bounds, and, unlike the soulless glare of the midwinter sun, is life-inspiring. There is a subtle essence in an April Sun that quickens the seeming dead.

And while I have stood wondering at this strange resurrective force, at times almost led to listen to the bursting buds and steadily expanding leaves, a veil is suddenly drawn over the scene and the light shadows fade to nothingness. Falling as gently as the sunlight that preceded it, come the round, warm rain-drops from a passing cloud. Gathering on the half-clad branches overhead, they find crooked channels down the wrinkled bark. poise upon the unrolled leaves, globes of unrivaled light, or nestle in beds of moss, gems in a marvelous setting. Anon the cloud passes, and every raindrop drinks its fill of light. There is no longer a flood of mellow sunshine here, but a sparkling light — an all-pervading glitter. And it is thoroughly inspiring. Your enthusiasm prompts you to shout, if you can not sing, and the birds are always quickly moved by it. From out their hidden haunts, in which they have sat silently while it rained, come here and there the robins, and, perching where the world is best in view, extol the merits of the unclouded skies. Ernest sun-worshippers they, that watch his coming with impatient zeal and are ever the first to break the silence of the dawn; and all these April days their varying songs are tuneful records of the changing sky.

IN THIS BIT OF FLOWERY PROSE, CHARLES CONRAD ABBOTT OFFERS UP HIS EASTERTIDE PAEAN TO A SPRING DAY IN THE FOREST. It is easy to dismiss the text as purple prose, or a thinly-veiled Christian allegory (though it might easily be seen as pantheistic, as well). Yes, it is perhaps overwrought. And yet, reading it, I am transported into the forest glade dripping in the light April rain, and it is a forest alive with color and light. It is an everyday landscape, probably somewhere on Abbott’s land (a blend of tidal marsh and upland on the edge of Trenton, New Jersey), and yet it is also a place of wonder and magic. Indeed, many past readers have evidently found fault with this; the Friends of the Abbott Marshlands (Abbott’s property is now a park) note that “Abbott’s writing about Natural History have sometimes been criticized for being more romantic than scientific.” For my part, though, I appreciate Abbott’s sincere, I think, efforts to combine scientific observation with a sense of aesthetic, affective, and perhaps even spiritual engagement with the landscape.

ABBOTT ALSO CELEBRATED NOT KNOWING. In an age rich with scientific and technological progress, Abbott was quick to point out what we still do not know (though now, more than one hundred years on, some of those things are indeed known). For instance, he wondered frequently about birds — the why behind their seasonal migration, their degree of intelligence, their individuality, their pair bonding, and the intention behind their behaviors:

Although there may be many who assume to know, it were, in truth, as idle to question the Sphinx as to attempt to unravel the mystery of bird ways. Again and again, as the year rolls by, the rambler must be content t merely witness., not to unfathom the whys and wherefores of a bird’s doing; but still this unpleasant experience does not go for naught. It very soon teaches him that birds are something beyond what those who should know better have asserted them to be. To learn this is a great gain. It is well to give heed to him or her who carries a spy-glass; but as to him who merely carries a shot-gun, and robs birds’ nests in the name of science, faugh!

(AND TO MAURICE THOMPSON I SAY, “FAUGH!”)

FOR THE MOST PART, ABBOTT WAS CONSISTENT IN ADVOCATING THE STUDY OF NATURE WITHOUT HARMING ANY LIVING BEINGS. If we ignore a troubling passage in which Abbott apparently put a lizard to sleep with chloroform gas and removed its eyes in an experiment about the sense capacities of reptiles, Abbott generally wrote, and acted, in ways that reflect a respect for all life. In that way, he put himself at odds with many contemporary scientists, amateur or professional. For instance, in this passage he defines natural history in ecological terms that seem rather ahead of its time (particularly in the notion of perceiving the world through the senses of another animal, experiencing its umwelt (nearly half a century before Jacob von Uexküll first coined the term).

To place stuffed birds and beasts in glass cages, to arrange insects in cabinets, and dried plants in drawers, is merely the drudgery and preliminary of study; to watch their habits, to understand their relations to one another, to study their instincts and intelligence, to ascertain their adaptations and their relations to the forces of nature, to realize what the world appears to them — these constitute, as it seems to me at. least, the true interest of natural history, and may even give us the clew to senses and perceptions of which at present we have no conception.

ANOTHER NOTEWORTHY FEATURE OF ABBOTT’S ENGAGEMENT WITH THE NATURAL WORLD WAS HIS DESIRE TO EXPERIENCE IT IN NOVEL WAYS. Consider, for instance, his suggestion that the nature enthusiast ought to consider looking up into the treetops while lying upon the ground:

It may not have occurred to ramblers generally, but to lie upon one’s back and study a tree-top, and particularly an old oak while in this position, has many advantages. If not so markedly so in October as in June, still the average tree-top is a busy place, though you might not expect it, judged by the ordinary methods of observation. If you simply stand beneath the branches of a tree or climb into them, you are too apt to be looked upon as an intruder. If you lie down and watch the play — often a tragedy — with a good glass, you will certainly be rewarded; and, not least of all, you can take your departure without some one or more of your muscles being painful from too long use. If the tree-top life deigns to consider you at all when you are flat upon your back, it will count you merely as a harmless freak of Nature.

THROUGHOUT THIS BOOK, CHARLES ABBOTT REFERS TO HIMSELF AS A “RAMBLER”; IN DOING SO, HE IS INTENTIONALLY PLACING HIMSELF IN THE COMPANY OF BURROUGHS, TORREY, FLAGG, AND THOREAU. Unlike Thoreau, but like all the others, Abbott writes in a consciously rambling style; his book is a collection of adventures, loosely strung together by the seasons of the year. Having read more than 30 books from this time period now, it is a format I have come to recognize readily. On the one hand, it is a style that was easier to write (not requiring much underlying structure) and pleasant to read (relating various encounters with plants, animals, and the weather). At the same time, it puts some limit on the overall quality of Abbott’s book. Without structure, it is ultimately without direction. While most of the book is set in and around his home acres in New Jersey, on a few occasions mid-chapter he would jump to another part of the state, or eastern Massachusetts, or even central Ohio (where Abbott, an archaeologist, spent some time at Serpent Mound). He didn’t even always stick to the month the chapter was about; at one point, he jumped from September back to May. I can see why the rambling nature essay format (a favorite with Torrey and Burroughs) eventually fell out of favor. Abbott is a fine writer, and this book has some charming passages; but the volume does not come close, in power or profundity, to Beston’s Outermost House.

TO CLOSE, I OFFER ONE MORE CHARMING PARAGRAPH OF ABBOTT’S WORK. Here, Abbott called for protecting old trees, an action I vigorously second:

Why, when such trees as are perfect specimens of their kind stand near public roads, can they not e held — well, semi-sacred, at least? Should not their owners be induced to let them stand? Indeed, could a community do better with a portion of the public funds than to purchase all such trees for the common good? Particularly is it true of a level country that the only bit of nature held in common is the sky. I would that here and there a perfect tree could be added to the list. I have known enormous oaks to be felled because they shaded too much ground and only grass could be made to grow beneath them. It is sad to think that trees, respected even by the Indians, should have no value now. The forest must inevitably disappear, but do our necessities require that no monuments to it shall remain?

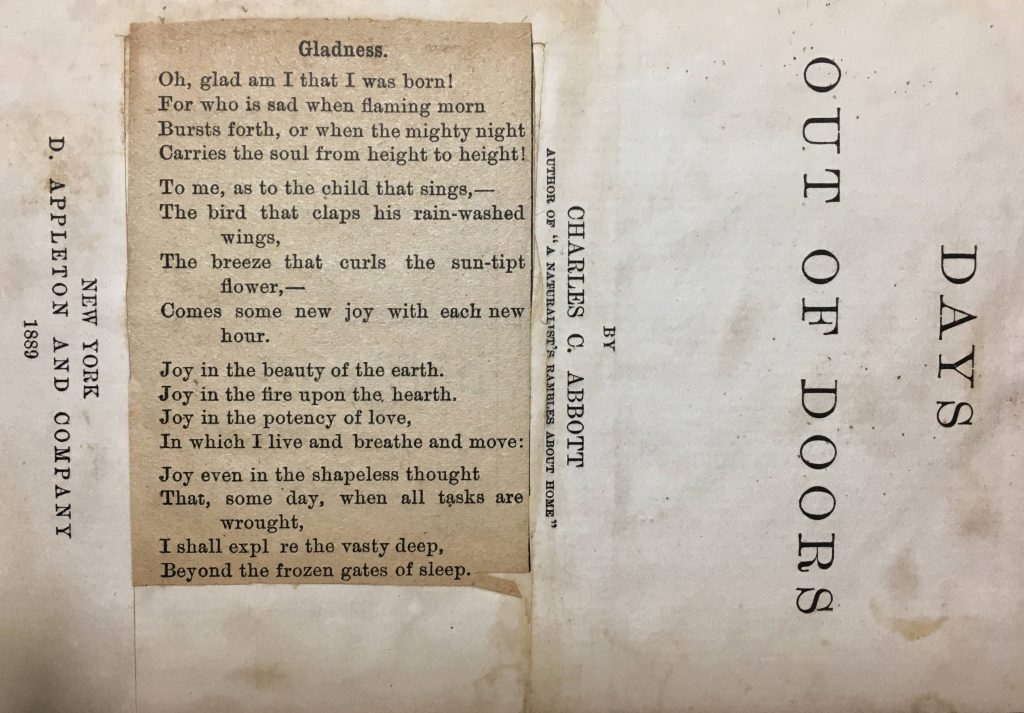

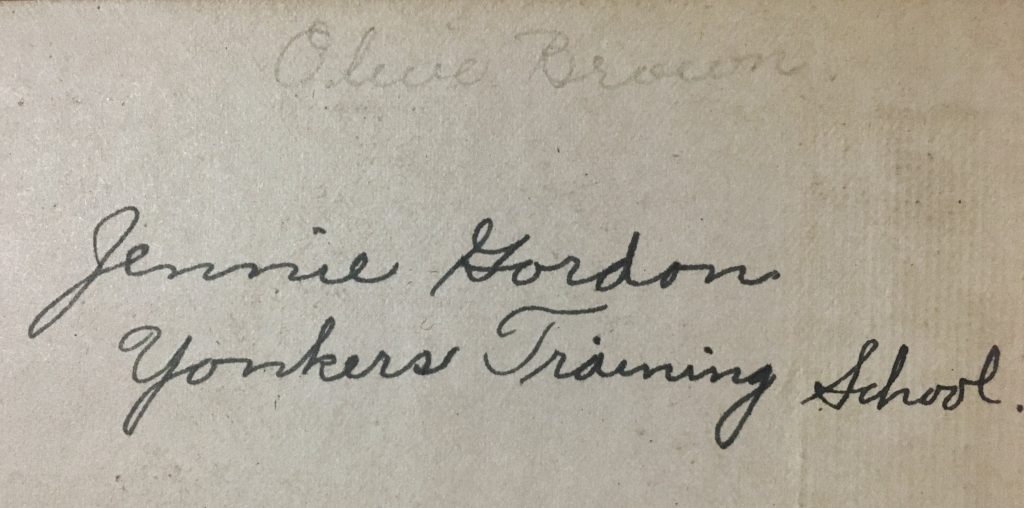

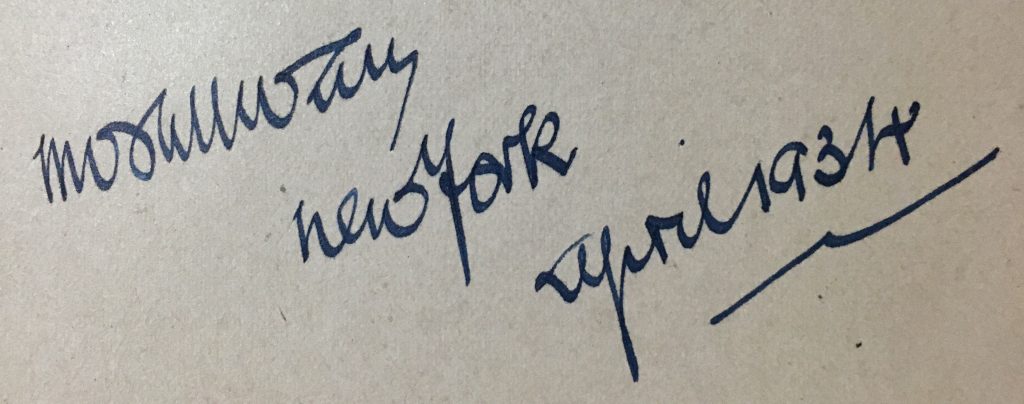

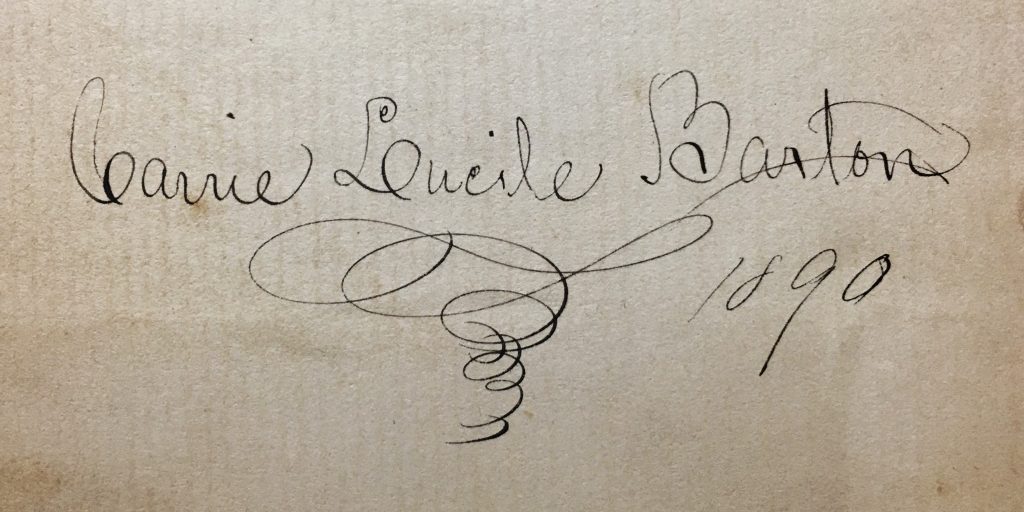

AS AN AFTERWARD, A FEW REMARKS ON THE STORIED BUT WEATHERBEATEN VOLUME I READ FOR THIS POST. The cloth at the spine is torn and loose, spine cocked, and part of edge of the front cover is missing. It is stained and tanned and the binding is loose. A collector’s copy it is not. In terms of history, as of 1890, it was owned by a Carrie Lucile Barton.

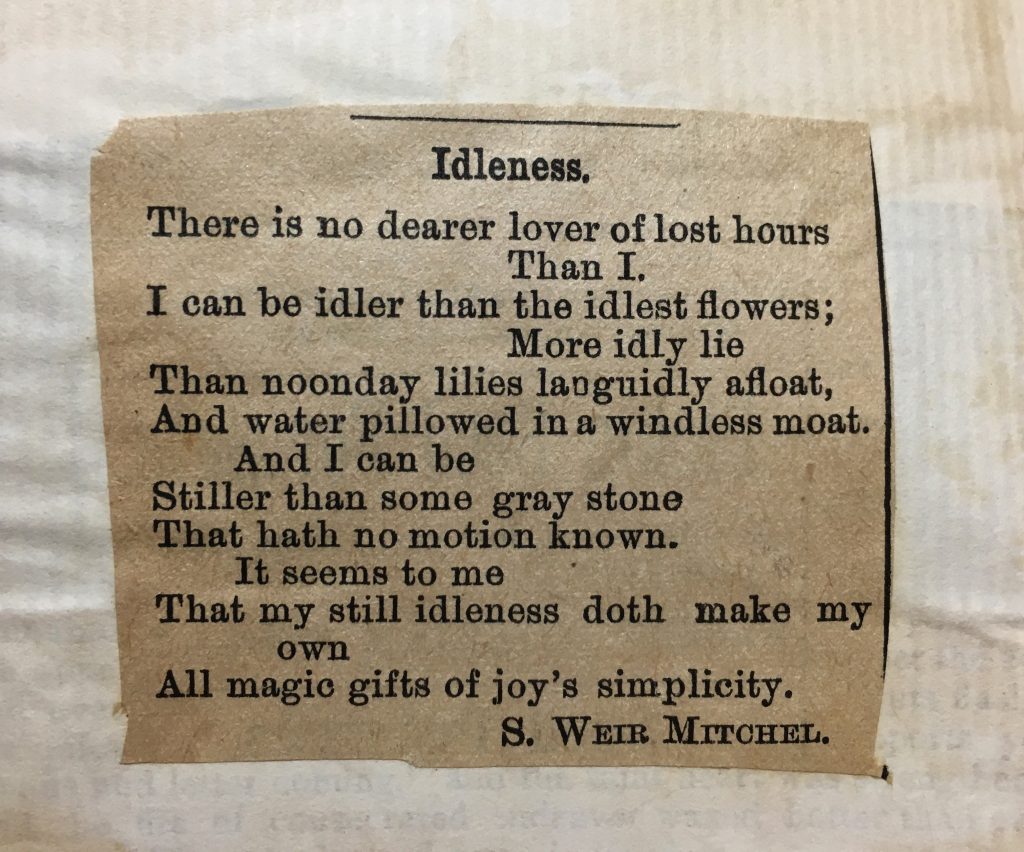

I have been able to find out very little about her online, but it is surprising there is anything at all. According to the National Register, in 1879 Carrie Lucile Barton was living in Washington, D.C., employed by the Coast Survey as a copyist. She had taken the position after living in Nebraska, though she was born in New York State. As confirmation that this is the same Carrie Barton as signed this book, I also found a Google links to a post mentioning that a Carrie Lucile Barton signed a copy of Les Misérables with her name and “Washington, D.C.” on December 3, 1888. Since my copy does not specify the location, did she move between 1888 and 1890? I also know a bit about her taste in poetry, if the two glued-in additions to the volume were her doing. Using Google again, I tracked the poem on the title page to Harriet Elizabeth Prescott Spofford, a highly published author of novels, poems, and detective stories. The other poem is by Silas Weir Mitchell, a physician, scientist, novelist, and poet. If I were asked to indicate a preference between the two, I think Mitchell is a bit more enticing, despite the “lilies languidly afloat”.