This is a beautiful world, and all who go out under the open sky will feel the gentle, kindly influence of Nature and hear her good tidings. The forests of the earth are the flags of Nature. They appeal to all and awaken inspiring universal feelings. Enter the forest and the boundaries of nations are forgotten.

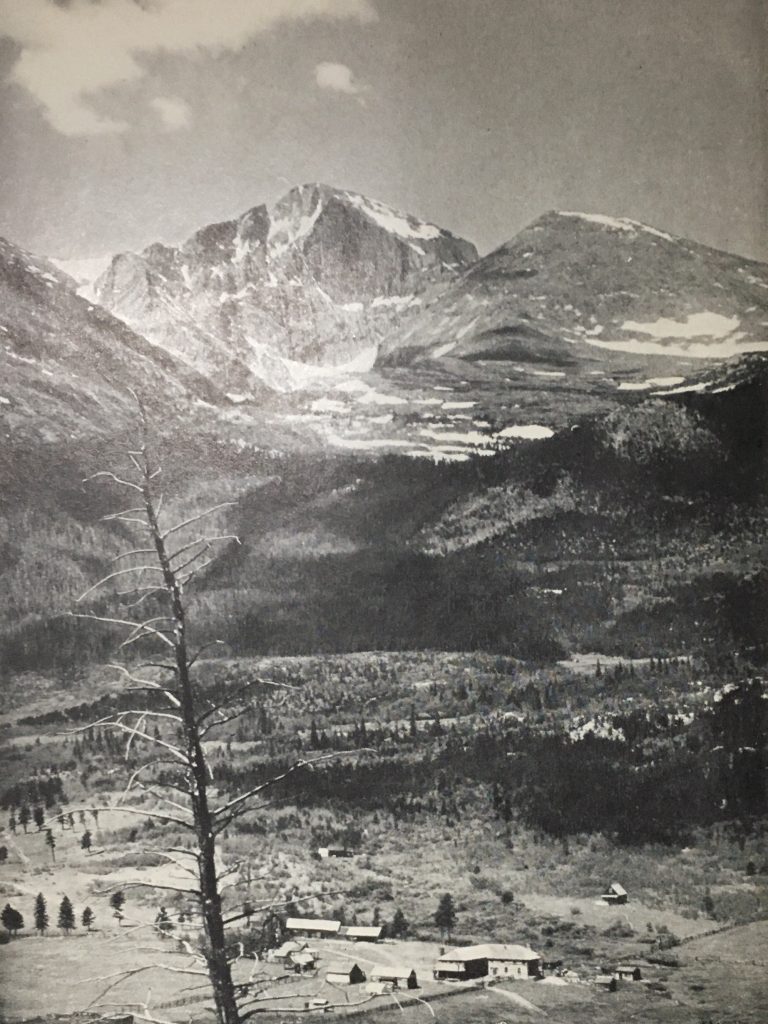

ENOS MILLS REMINDS ME VERY MUCH OF JOHN MUIR. The resemblance is far from accidental; in 1889, Mills chanced upon John Muir at a beach in San Francisco, and the experience left him seeking to emulate the master in his celebration of the western landscape. In fact, he even referred to himself as “John Muir of the Rockies” — popularizing the wild wonders of the Colorado Rockies and the joys of living a rugged life among them. From his cabin in Estes Park (now a museum), he led numerous trips into the Rockies, including hundreds of ascents up Long’s Peak. Like Muir, he had a charming, loyal, highly intelligent dog companion (Scotch); like Muir, he never carried a gun and respected all wildlife; like Muir, he played a vital role in the development of the National Park system and the preservation of wild mountains; like Muir, he had many dramatic adventures in the wild that he shared in his books; and like Muir, he saw encountering nature as a means of connecting with God. But unlike Muir, almost no one has heard of him nowadays. And I think that is a tragic loss.

I CURRENTLY HAVE TWO OF MILLS’ BOOKS; TWO MORE ARE ON THEIR WAY; I ALSO HAVE HIS BIOGRAPHY. In the coming months, I will revisit him many times in this blog. His writing is superb; it flows beautifully, evoking the splendors of the Rockies without being pedantic or flowery. If anything, Mills was remarkably humble about his exploits. And in so many ways, his perception of the environment was far ahead of its time (or at very least, on the leading edge of a new ecological awareness). Consider, for instance, his essay on The Story of a Thousand-Year Pine. I suspect it is one of the earliest essays ever written for a popular audience in the field of dendrochronology. He opens with an homage to Muir:

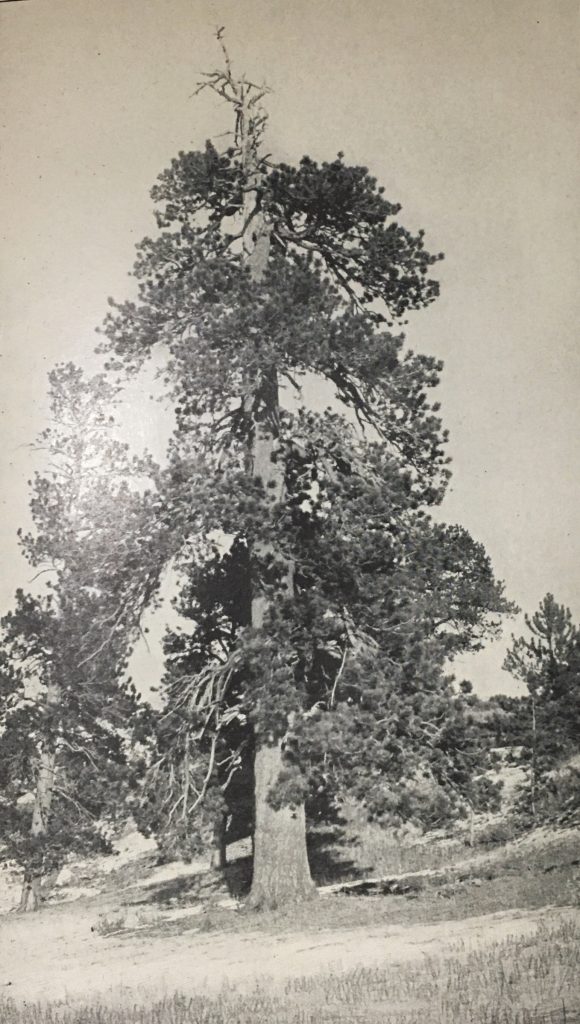

The peculiar charm and fascination that trees exert over many people I have always felt from childhood, but it was that great nature-lover John Muir, who first showed me how and where to learn their language. Few trees, however, ever held for me such an attraction as did a gigantic and venerable yellow pine which I discovered one autumn day several years ago while exploring the southern Rockies. It grew within sight of the Cliff-Dwellers’ Mesa Verde, which stands at the corner of four States, and as I came upon it one evening just as the sun was setting over that mysterious tableland, its character and heroic proportions made an impression upon me that I shall never forget, and which familiar acquaintance only served to deepen while it yet lived and before the axeman came. Many a time I returned to build my camp-fire by it and have a day or night in its solitary and noble company.

ALAS, THE LOGGERS CAME AT LAST. In an indescribable tragedy, when the tree was felled, it crashed to the ground with such a resounding blow that the trunk was shattered. The loggers abandoned it as being of little value. Withholding comment on the loss of such a noble tree, Mills reports how he set to work piecing together its past: “Receiving permission to do as I pleased with his remains, I at once began to cut and split both the trunk and the limbs and to describe their strange records.” Carefully counting its rings, he discovered the tree had been born in about 856, and was felled in 1903, having lived 147 years. Over the next ten pages, Mills told the story of the pine’s remarkable life, including periods of drought, possible earthquakes, encounters with Indians, and episodes of fire. All in all, it is a remarkable bit of detective work, decades before radiometric dating was developed.

ANOTHER AMAZING ESSAY IN THIS BOOK IS ON THE BEAVER AND HIS WORKS. Based upon extensive observations of beavers in the Rockies and the surrounding region, Mills gave an account of the incredible engineering work beavers have accomplished — including a dam on the South Platte River that was over a thousand feet long! What makes the essay so impressive, however, is how he was able to extrapolate from what he witnessed beavers doing to a sense of the considerable role they had played in shaping the Western landscape:

[The beaver’s] engineering works are of great value to man. They not only help to distribute the water s and beneficially control the flow of the streams, but they also catch and save from loss enormous quantities of the earth’s best plant-food. In helping to do these two things — governing the rivers and fixing the soil — he plays an important part, and if he and the forest had their way with the water-supply, floods would be prevented, streams would never run dry, and a comparatively even flow of water would be maintained in the rivers every day of the year.

Later in the essay, he proposes that

An interesting and valuable book could be written concerning the earth as modified and benefitted by beaver action, and I have long thought that the beaver deserved at least a chapter in Marsh’s masterly book, “The Earth as modified by Human Action.” To “work like a beaver” is an almost universal expression for energetic persistence, but who realizes that the beaver has accomplished anything? Almost unread of and unknown are his monumental works.

In fact,

Beaver-dams have had much to do with the shaping and creating of a great deal of the richest agricultural land in America. To-day there are many peaceful and productive valleys the soil of which has been accumulated and fixed in place by ages of engineering activities on the part of the beaver before the white man came. On both mountain and plain you may still see much of the good work accomplished by them. In the mountains, deep and almost useless gulches have been filled by beaver-dams with sediment, and in course of time changed to meadows. As far as I know, the upper course of every river in the Rockies is through a number of beaver-meadows, some of them acres in extent.

Alas, the beavers were dying out, and that would lead inevitable to changes in the Western landscape:

Only a few beavers remain, and though much of their work will endure to serve mankind, in many places their old work is gone or is going to ruin for the want of attention. We are paying dearly for the thoughtless and almost complete destruction of the animal. A live baver is far more valuable to us than a dead one. Soil is eroding away, river-channels are filling, and most of the streams in the United States fluctuate between flood and low water. A beaver colony at the source of every stream would moderate these extremes and add to the picturesqueness and beauty of many scenes that are now growing ugly with erosion. We need to coöperate with the beaver. He would assist the work of reclamation, and be of great service in maintaining the deep-waterways. I trust he will be assisted in colonizing our National Forests, and allowed to cut timber there without a permit.

I WILL CLOSE WITH ONE MORE LOVELY PASSAGE CELEBRATING THE WESTERN WILDS. In this case, Mills is reminiscing about a trip into the Uncompahgre Mountains, where he spent many nights in solitude beside a campfire, miles from anyone:

The blaze of the camp-fire, moonlight, the music and movement of the winds, light and shade, and the eloquence of silence all impressed me more deeply here than anywhere else I have ever been. Every day there was a delightful play of light and shade, and this was especially effective on the summits; the ever-changing light upon the serrated mountain-crests kept constantly altering their tone and outline. Black and white they stood in madday glare, but a new grandeur was born when these tattered crags appeared above storm-clouds. Fleeting glimpses of the crests through s surging storm arouse strange feelings, and one is at bay, as though having just awakened amid the vast and vague on another planet. But when the long, white evening light streams from the west between the minarets, and the black buttressed crags wear the alpine glow, one’s feelings are too deep for words.

MY COPY OF MILLS’ BOOK IS A LIBRARY REBIND. On the one hand, that means that the binding is really sturdy; on the other hand, the pain forest green cloth is no replacement for the decorated cover with its image of a bear on a snow-blanketed rock. However, the interior is the original first edition of the book from 1909. For some time, it was evidently the property of the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library, not far from my home.