In these softer modern days, when we all desire the valley warmth, the nervous companionship of our kind, the handy motion-picture theatre, many an upland pasture is going back to wildness, invaded by birch and pine upon the borders, overrun with the hosts of the shrubby cinquefoil, most provocative of plants because it refuses to blossom unanimously, putting forth its yellow flowers a few at a time here and there on the sturdy bush. Such a pasture I know upon a hilltop eighteen hundred feet above the sea, where now few cattle browse, and seldom enough save at blueberry season does a human foot pass through the rotted bars or straddle the tumbling, lichen-covered stone wall, where sentinel mulleins guard the gaps. It is not easy now even to reach this pasture, for the old logging roads are choked and the cattle tracks, eroded deep into the soil like dry irrigation ditches, sometimes plunge through tangles of hemlock, crossing and criss-crossing to reach little green lawns where long ago the huts of charcoal burners stood, and only at the very summit converging into parallels that are plain to follow. Some of them, too, will lead you far astray, to a rocky shoulder of the hill guarded by cedars, where you will suddenly view the true pasture a mile away, over a ravine of forest. Yet once you have reached the true summit pasture, there bursts upon you a prospect the Lake country of England cannot excel; here the northbound [white-throated sparrows] rest in May to tune their voices for their mating song, here the everlasting flower sheds its subtle perfume on the upland air, the sweet fern contends in fragrance, and here the world is all below you with naught above but Omar’s inverted bowl and a drifting cloud.

It is good now and then to hobnob with the clouds, to be intimate with the sky. “The world is too much with us” down below; every house and tree is taller than we are, and discourages the upward glance. But here in the hilltop pasture nothing is higher than the vision save the blue zenith and the white flotilla of the clouds. Climbing over the tumbled wall, to be sure, the grass-line is above your eye; and over it, but not resting upon it, is a great Denali of a cumulus. It is not resting upon the pasture ridge, because the imagination senses with the acuteness of a stereoscope the great drop of space between, and feels the thrill of aerial perspective. Your feet hasten to the summit, and, once upon it, your hat comes off, while the mountain wind lifts through your hair and you feel yourself at the apex and zenith of the universe. Far below lie the blue eyes of Twin Lakes, and beyond them rises the beautiful dome of the Taconics, ethereal blue in colour, yet solid and eternal. Lift your face ever so little, and the green world begins to fall from sight, the great cloud-ships, sailing in the summer sky, begin to be the one thing prominent. How softly they billow as they ride! How exquisite they are with curve and shadow and puffs of silver light! Even as you watch, one sweeps across the sun, and trails a shadow anchor over the pasture, over your feet. You almost hold your breath as it passes, for it seems in some subtle way as if the cloud had touched you, had spoken you on its passage.

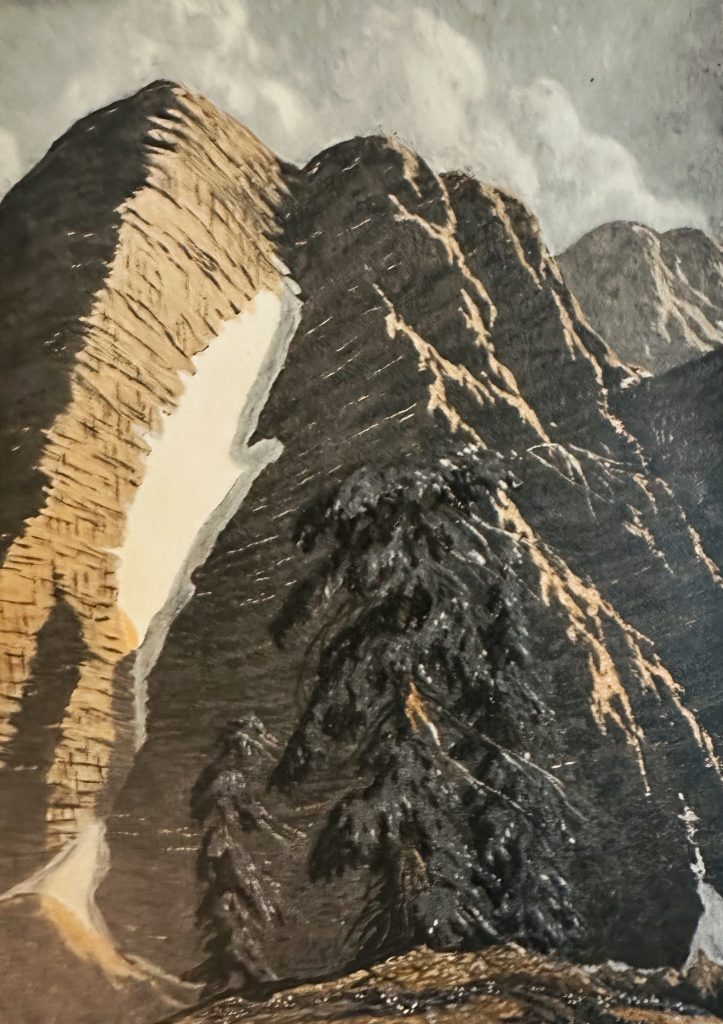

What an exultant, rhapsodic love song to an upland pasture in the Berkshires of Massachusetts! One hundred years ago, the once-productive fields were slowly turning back to forest, and it was possible to gaze a great distance across the changing landscape. And in this passage, Walter Prichard Eaton captured the sublime vision in such flowing prose. He wrote about a place he new well, where he and his wife would escape the hustle and bustle of the East Coast cities. Clearly he treasured it deeply. Yet for all eight colored artworks illustrating the volume, only one is from his home, and it is a nondescript, practically black and white image of two deer drinking at the edge of a lake at twilight. The remainder of the images are from Pritchard’s extensive travels out west. Yet without doubt, this evolcation of a place he knew so well and frequented so often is the highlight of this volume. When he wrote of Western landscapes, he shared them as an outsider, identifying trails traversed and plants observed in flower. The poetic spirit infusing the lines above is missing. As it is, unfortunately, from most of the book.I am reading a biography of Mary Treat, author of Home Studies in Nature that I wrote about in this blog ages back. One might argue that Mary is unknown in large part because she was a woman in an age when only men were recognized for their scientific accomplishments. While women authored books, few of them from this period are remembered today. But what of Mr. Prichard Eaton, a white male and scholar, who published several books (stay tuned for more) yet is forgotten today. What excuse might we offer for him? I am beginning to realize that some forgotten authors may be forgotten for good reason. Yes, there are beautiful swathes of text. But was it worth the long journey across over 300 pages to encounter them? I am not so sure.

The major harvest of our pasture is undoubtedly the apple crop, and the major harvesters are the deer. The apples are small and bitter or else tasteless now. Encouraged by the optimism of Thoreau, I have bitten into many hundreds of wild apples since I first read his immortal psean in their praise, but I have yet to discover a second Baldwin, or even an equal of the poorest variety in our orchard crop. At any rate, I no longer pick the apples in this pasture. No one picks them. They fall to the ground on an autumn night, and no one hears the soft, startling thud in the silence of the forgotten clearing. But the squirrels and the deer know where they are.

True, Walter Prichard Eaton does have a (brief) Wikipedia entry, along with an obituary in the New York Times. He lived from 1878 until 1957. Born in Molden, Massachusetts and a graduate of Harvard, he was a theater critic for various newspapers, and wrote a number of books on theater and nature. He was also a professor of play writing at Yale from 1933 until 1947. He was a staunch enemy of the movie industry, strongly preferring the theatrical stage. His obituary notes that Eaton’s “tales of woodland ramblings were not as recognized as they deserved to be, according to one critic.” Hmm…

As a casual observer of nature with a busy professional career writing about plays (and writing a few of his own), perhaps he can be forgiven for a focus on the scenery rather than diving more deeply into the landscape. He identifies some birds and some plants, but I suspect he did not spend many hours with a hand lens, deeply observing the minute worlds of a mossy log or a woodland pool along a stream. He did, at least, express some familiarity with Thoreau. Like James Buckham 22 years earlier, for instance, he experimented with winter apples, but with less successful results:

When not writing about the Berkshire landscape or his adventures out West, Eaton was also prone to Norman Rockwell moments — descriptions of old covered bridges, barns, and the like. There are definitely hints of long here for the rural America of his boyhood, complete with itinerant ragmen, tin peddlers, and rural mail carriers. These were passing away, replaced by automobiles and — heaven forbid! — movie theaters. I find it strangely comforting that, just as I often look back on my own past in the days before Internet and iPhone, Eaton looked back on a slower, gentler age in his youth.

But there are still those rare moments, moments where he captures a view in a particularly engaging way. Here is another one, this time describing a flowing stream, as seen from the bow of a canoe wending its way through the twists and turns with the current:

We enter a canoe — a canoe because it slips noiselessly through the water, and can go almost anywhere and examine the river bank more closely, with quite a new impression of its size here on the surface of the water, where it towers six feet above us and shuts out all but the tops of the mountains. It is composed of compact layers of loamy sand, with here and there a little slippery clay. The constant erosion of the water at freshet time has hollowed it out beneath the surface soil, and the grass and flowers, holding together the surface overhang by tenacious roots, curve out and droop along the top like peat thatching. Each Spring great chunks of this overhang break away and fall into the water, as the river continues to deepen the bend. Under this thatch, looking quaintly like a street of Upper West Side apartment houses, are the dark little holes of the bank swallows, row after row of them, neatly tunnelled into the damp brown earth. The swallows skim low over the surrounding fields, snapping up insects as they fly, or come home unerringly to their abodes and disappear with a flutter of tail. The nests are so exactly similar in appearance that one marvels at the birds’ discrimination. It is fortunate, certainly, that sobriety is one of their virtues. Now and then among the swallows’ cliff dwellings is a larger hole, where dog or woodchuck or predatory rat has burrowed, hunting, perhaps, for eggs.

The complementary tongue of land which is always formed by the river opposite one of these concave sweeps of exposed bank is no less interesting. Close to the water it is like a sand bar, forming an excellent shelving beach for bathing, and a playground for the sandpipers and the plovers. You may often come upon a flock of these birds on a bar, as your canoe rounds the bend, running back and forth and bobbing their heads up and down. “Tip ups,” some boys call them. But back a few feet from the new shelf of the bar, the receding waters have deposited soil and seeds, and last year’s deposit is already rank and green with swampy verdure. Then the willows begin. Almost every new tongue of land has its clump of willows, sown by the sweep of the stream on a curve as regular as any topiary artist could lay down, and trimmed to a uniform height. There is one long bend on our river, perhaps four hundred yards in extent, which is not a sharp but a gradual curve. The river was evidently nearly straight at this point a generation or two ago, but something deflected its current perhaps a tree which fell into the water and piled up a dam of roots and tangled flotsam. The current, swinging out from this new obstruction, ate into the farther bank and gradually channelled a great bend, depositing new land on the eastern side. Along high -water mark on this new land, following the new curve of the channel, it planted a hedge of willow possibly fifteen years ago. That hedge is now thirty feet high, as uniform along the top as though it were annually trimmed, and presenting an unbroken wall of shimmering, delicate green set on the sweeping curve of the stream, with a pink garden of Joe-pye-weed at its feet. There is no gardener like the river when you give him a chance!

Finally, in closing, I offer this passage on trees and their personalities. Could Eaton have read Royal Dixon’s book on the topic, “The Human Side of Trees” (1917), perhaps?

Trees, of course, are the most beautiful as well as the most useful of growing things, not because they are the largest but because they attain often to the finest symmetry and because they have the most decided and appealing personalities. Any one who has not felt the personality of trees is oddly insensitive. I cannot, indeed, imagine a person wholly incapable of such feeling, though the man who plants a Colorado blue spruce on a trimmed lawn east of the Alleghanies, where it is obliged to comport itself with elms and trolley cars, is admittedly pretty callous. Trees are peculiarly the product of their environment, and their personalities, in a natural state, have invariably a beautiful fitness.

No, haven’t given up on Walter Prichard Eaton, not quite yet. In fact, I have four more volumes of his waiting on my shelf, three of which I tracked down after finishing this one. But I think I will save them for later.

Addendum: When I first wrote this post, I neglected to mention a bit of side path I ended up following as a result of a passage early on in Eaton’s book. Describing a New Hampshire landscape, he noted that “Behind the oak looms the great north peak of Kinsman, which can now be climbed, thanks to a trail recently cut by the son of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman, whose collected poems, published in 1860, have been quite unjustly forgotten.” Taking up the challenges, I looked up Frederick Tuckerman, and discovered that his complete poems were republished in 1965, in a volume edited by no other than N. Scott Momaday! I have since tracked down the work (which is long out of print), and will be sharing my gleanings from it in a future blog post.