Winds…circle about New England. They form a ring about it; they lie in wait on its borders, but only to spring upon it and harry it. They follow each other in contracting circles, in whirlwinds, in maelstroms of the atmosphere; they meet and cross each other, all at a moment. This New England is set apart; it is the exercise ground of the weather. Storms bred elsewhere come here full-grown; they come in couples, in quartets, in choruses. If New England were not mostly rock, the winds would carry it off; but they would bring it all back again, as happens with the sandy portions. What sharp Eurus carries to Jersey, Africus brings back. When the air is not full of snow, it is full of dust. This is called one of the compensations of Nature.

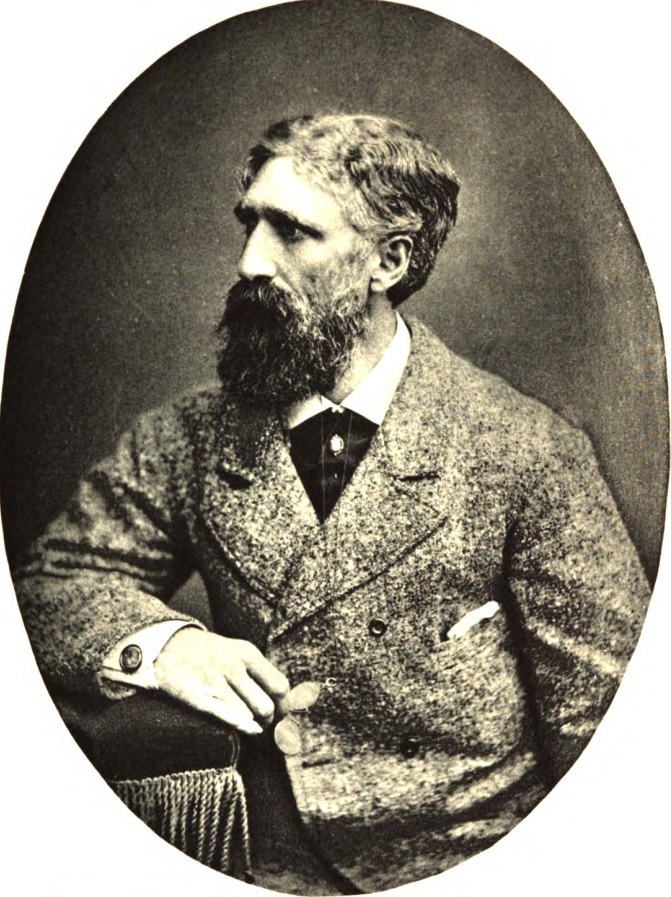

AFTER SO MANY SERIOUS INVESTIGATIONS OF OUR RELATIONSHIP TO NATURE, CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER’S ESSAYS ARE DELIGHTFUL SPRING BREEZES. Charming in their levity and rich in exaggeration, they explore (even celebrate) a contrary outlook on Nature. For Warner, Nature is capricious, somewhat dangerous (though not too hostile), and something best appreciated in short spells punctuated by comfortable hours at the fireside at home. Warner’s writing style is reminiscent of Mark Twain’s; indeed, the two co-authored a book, “The Gilded Age”, just two years before Warner published this one. But unlike Mark Twain, at the root of all the humor is a light-heartedness. Yes, nature can be really unpleasant, but time spent out of doors still translates into joyful memories, and the wanderer lost in the woods finds his way home at last with relatively few mishaps. At the close of his essay Camping Out, after two nights of soaking rain in a waterlogged camp in the woods, for instance, Warner remarks that most of the folks on the outing will likely return to the woods again, “For he who has once experienced the fascination of the woods-life never escapes its enticement; in the memory nothing remains but its charm.”

MY FAVORITE ESSAY IN THIS SLENDER VOLUME, WITHOUT A DOUBT, IS LOST IN THE WOODS. For anyone who has had that singular experience (as I have, through no fault but my own, not five miles from my doorstep), the essay rings true. And it is hilarious. My greatest complaint about Warner is that his essays are mostly too brief. I could read on and on about his travails getting home after a day of fly fishing in a mountain gorge (an adventure that yielded him only one small trout. (“Never were there such places for trout; but the trout were out of their places.”) Take, for instance, this scene in which Warner, pushing through the woods for hours with night approaching, finally consults his compass with a less than desirable outcome:

It then occurred to me that I had better verify my course by the compass. There was scarcely light enough to distinguish the black end of the needle. To my amazement, the compass, which was made near Greenwich, was wrong. Allowing for the natural variation of the needle, it was absurdly wrong. It made out that I was going south when I was going north. It intimated, that, instead of turning to the left, I had been making a circuit to the right. According to the compass, the Lord only knew where I was.

The inclination of persons in the woods to travel in a circle is unexplained. I suppose it arises from the sympathy of the legs with the brain. Most people reason in a circle: their minds go round and round, always in the same track. For the last half hour I had been saying over a sentence that started itself: “I wonder where the road is!” I had said it over till it had lost all meaning. I kept going round on it; and yet I could not believe that my body had been travelling in a circle. Not being able to recognize any tracts, I have no evidence that I had so travelled, except the general testimony of lost men.

The compass annoyed me. I’ve known experienced guides utterly discredit it. It could n’t be that I was to turn about, and go the way that I had come. Nevertheless, I said to myself: “You’d better keep a cool head, my boy, or you are in for a night of it. Better listen to science than to spunk.” And I resolved to heed the impartial needle.

On the right direction back to the inn at last (but still not having come across the road to take him there), Warner confronts his hunger in the wilds of the Adirondacks:

I began to be a question whether I could hold out to walk all night; for I must travel, or perish. And now I imagined that a spectre was walking by my side. This was Famine. To be sure, I had only recently eaten a hearty luncheon; but the pangs of hunger got hold on me when I thought that I should have no supper, no breakfast; and, as the procession of unattainable meals stretched before me, I grew hungrier and hungrier. I could feel that I was becoming gaunt, and wasting away: already I seemed to be emaciated. It is astonishing how speedily a jocund, well-conditioned human being can be transformed into a spectacle of poverty and want. Lose a man in the woods, drench him, tear his pantaloons, get his imagination running on his lost supper and the cheerful fireside that is expecting him, and he will become haggard in an hour. I am not dwelling on these things to excite the reader’s sympathy, but only to advise him, if he contemplates an adventure of this kind, to provide himself with matches, kindling-wood, something more to eat than one raw trout, and not to select a rainy night for it.

Nature is so pitiless, so unresponsive, to a person in trouble! I had read of the soothing companionship of the forest, the pleasure of the pathless woods. But I thought, as I stumbled along in the dismal actuality, that if I ever got out of it I would write a letter to newspapers, exposing the whole thing. There is an impassive, stolid brutality about the woods that has never been enough insisted on.

His response to his plight is to rail at Nature, sounding a marked counterpoint to all those nature-seekers of the day. Of course, when one considers the minor nature of Warner’s actual circumstances (versus survival stories of marooned athletes that wind up eating each other, for instance), the words begin to seem more comical than sincere. His quite rational reaction to this realization of nature’s brutality is to contemplate harm to the vegetation:

It seemed to me that it would be a sort of relief to kick the trees. I don’t wonder that the bears fall to, occasionally, and scratch the bark off the great pines and maples, tearing it angrily away. One must have some vent to his feelings. It is a common experience of people lost in the woods to lose their head; and even the woodsmen themselves are not free from this panic when some accident has thrown them out of their reckoning. Fright unsettles the judgement: the oppressive silence of the woods is a vacuum in which the mind goes astray. It’s a hollow sham, this pantheism, I said; being “one with Nature” is all humbug: I should like to see somebody. Man, to be sure, is of very little account, and soon gets beyond his depth; but the society of the least human being is better than this gigantic indifference. The “rapture on the lonely shore” is agreeable only when you know you can at any moment go home.

ONE OTHER ESSAY IN THE BOOK IS PARTICULARLY WORTH NOTING; A-HUNTING OF THE DEER. Most of the tale is told from the deer’s point of view. It is a tragic story in which a mother deer is forced by approaching hounds to abandon her fawn to keep it protected, leading the hounds on a chase down the hill, through a town, and up another mountain, concluding at a lake. Everywhere she runs, people have guns pointed at her. Finally, exhausted, swimming out into a lake to escape the approaching dog, she is knocked unconscious by a boat paddle and killed with a knife to the jugular vein. The poor fawn survives, but is left in the company of a buck who cannot provide the young deer with the food it needs. It is certainly Warner’s most tragic tale, accentuated by his emphasis on the innate brutality of humans:

In a panic, frightened animals will always flee to human-kind from the danger of more savage foes. They always make a mistake in doing so. Perhaps the trait is the survival of an era of peace on earth; perhaps it is a prophecy of the golden age of the future. The business of this age is murder, — the slaughter of animals, the slaughter of fellow-men, by the wholesale.

LEST THE READER IMAGINE THAT WARNER HIMSELF WAS NOT FOND OF NATURE, I WILL CLOSE WITH A PASSAGE FROM AN EXCERPT FROM HIS ESSAY, WHAT SOME PEOPLE CALL PLEASURE. It is about his part in a hiking expedition ascending Nipple Top, a peak adjacent to Mount Marcy in the Adirondacks. Perhaps it is the sunnier weather (so many of Warner’s essays are set on stormy days), but here we have a different response to Nature, one more aesthetic and even celebratory:

The afternoon was bright; there was a feeling of exultation and adventure in stepping off into the open but pathless forest; the great stems of deciduous trees were mottled with patches of sunlight, which brought out upon the variegated barks and mosses of the old trunks a thousand shifting hues. There is nothing like a primeval wood for color on a sunny day. The shades of green and brown are infinite; the dull red of the melock bark glows in the sun, the russet of the changing moose-bush becomes brilliant; there are silvery openings here and there; and everywhere the columns rise up to the canopy of tender green which supports the intense blue sky and holds up a part of it from falling through in fragments to the floor of the forest. Decorators can learn here how Nature dares to put blue and green in juxtaposition; she has evidently the secret of harmonizing all the colors.

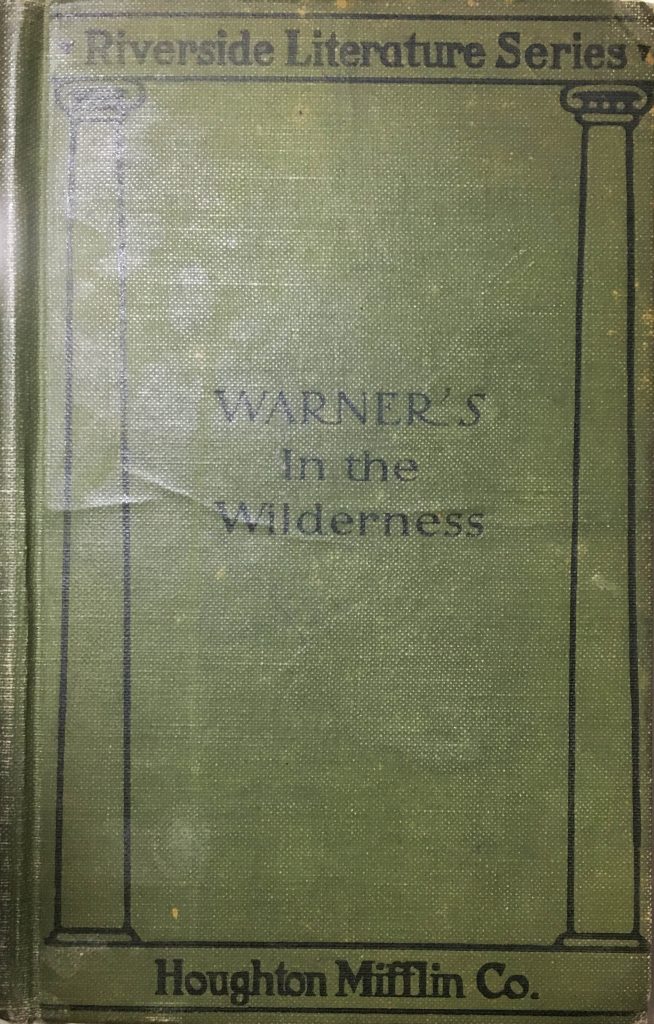

A FEW CLOSING WORDS ABOUT MY COPY OF THIS BOOK. Originally published in 1875, it was reprinted by Houghton Mifflin Company in 1905 as part of its Riverside Literature Series. My copy is actually copyright 1906 by Susan Lee Warner, his widow. The flyleaf identifies Sam Webb, at 852 Fifth Avenue in New York (in case anyone wants to try to locate him) as the author. The penmanship suggests a child’s hand. There is also the year 1922 written on the flyleaf, also in blue ink but not near the name. For the sake of a narrative, let’s assume he obtained the book then. There is also a bookplate on the inside front cover for The Pierson Library in Shelburne, Vermont. According to that, the book was a gift of Mrs. J. W. Webb, 3/10/30. My guess would be that she was Sam’s mother, who donated his book to a library after he was finished with it (and perhaps had gone off to college). The word “discarded” is written across the bookplate, but the date of that event is unknown. Below is a photograph of the library entrance as it looked prior to 2019, when a town center revitalization project was undertaken, including what appears to be an entirely new library building. Perhaps this book was discarded as part of a general review of library holdings prior to this.