From all we can gather it appears most probable that in its present form our songbird proper– our bird with a song to sing — is not much older than man; that he found his song just in time to gladden the ears of God’s last and greatest creation; that he struggled through countless ages and awful changes in order to fit himself for our entertainment. Think what the avian race has endured since first Archaeopteryx felt the feathers begin to bud in his arms! What a long, slow, hesitating, faltering current of development, from a scaly amphibian of the paleozoic time, up, up, to the glorious state of the nightingale and the mocking-bird! I never see a brown thrush flashing his brilliant song from the highest spray of a tree without letting a thought go back over the way he has come to us, and I always feel that to protect and defend the song-bird is one of man’s clearest duties.

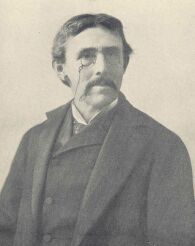

I REALLY WANT TO FIND SOMETHING TO LIKE ABOUT MAURICE THOMPSON. The closest I can come is the close of this quote, in which Thompson — the same one that two years previously (as documented in my last post) killed one ivory-billed woodpecker and destroyed the nest of another pair — argues that we ought to protect songbirds. Of course, his rationale doing so is pure 19th Century anthropomorphism. Everything was created for us, pure and simple. Add to that the Great Chain of Being, a warped mismash of the Bible and Darwin, and a really bizarre explanation of the driving force behind evolution, and you have Thompson’s outlook on nature. History books celebrate the winners — the ones who get it right, the ones “ahead of their times”. Thompson most assuredly was not one of those. But his writing does offer a window into a long-gone age of American society, one in which the passenger pigeon, the Carolina parakeet, and the ivory-billed woodpecker all were driven rapidly toward extinction. What mindset made that possible? Here is another passage dripping with anthropocentrism and human entitlement:

The inspired record [the Bible] declares that man was given dominion, which would imply that the earth and all things upon it and in it were made for his benefit. Science may profit by this view of creation, and take the serving of man’s physical and mental needs as the end of evolution. In other words, we may assume that if the object of creation was to make a sphere of man’s dominion while in the human state, then all the lines of creature development have been drawn towards a culmination, have been led to their highest point, in the age of man’s creation; that the Creator perfected the animal, mineral, and vegetable kingdoms before he made man.

WHAT EMERGES IS A SEQUENCE OF LIFE, FROM PRIMITIVE AND LACKING MERIT TO HIGHLY EVOLVED AND MERITORIOUS. In this way, tacking the concept of evolution onto the notion of creation by God, Thompson offers a model in which man reigns supreme and can bask in the knowledge that it has been a long evolutionary journey to arrive at the human being:

All the more honor to the man if indeed he has come up from the germ in the old dust of chaos, has wriggled past the worms, swam past the fishes, outstripped the birds, and made himself the lord of all the animals. Indeed, as I sit here in this tropical springtide, with my eyes full of color-visions and my ears full of soothing sounds, I am willing to consider myself a manifestation of nature’s patient work, the end of a labor begun when life first stirred in the most favored spot of the earth.

THINGS GET REALLY CRAZY ONCE THOMPSON PULLS OUT HIS “SCIENTIFIC” EXPLANATION FOR HOW EVOLUTION WORKS. In his model, it is, well, I will let him explain instead:

Evolution is the outcome of natural desire, and natural desire has been generated by a disturbance of natural equilibrium. There is nothing abstruse or occult in this proposition; it is merely a recognition of the development of intelligence and of the controlling power of the brain in animals.

Lest that seem a bit bewildering, Thompson offers the model in much simpler terms a few pages later:

Evolution tinges everything. One grows like what one contemplates….

My elementary school cafeteria got it wrong: you aren’t what you eat. Instead, you are what you think. And your offspring, over many generations, will become more and more of that. For example,

Birds of the polar areas of snow and ice are white, those of the tropics are vari-colored and brilliant-hued. The condition in each instance has been reached by a natural desire to hide by blending with the prevailing tone of Nature.

And here is a different example:

In the case of wading birds, those species which have chosen to live near small streams have shorter legs and neck that species which prefer larger streams, lakes or sea-borders, and, taking the little green heron as an example, as our streams diminish in volume year by year, the bird modifies its habit in accordance with necessity, and in my mind there is no doubt that its legs and neck will be affected, in the course of a comparatively short period, to a noticeable degree.

If animals evolve by the choices they make and the things they desire, then it follows that it is possible to make better or worse choices. Consider the case of the flying frog of Borneo:

Here is a strange, belated effort of nature to urge the scaleless reptiles up to arboreal, aerial, and song-singing life, by the side of their more fortunate avian kinsmen, who early chose a better method of development!

And yes, this model of various levels (orders) of relative quality extends to other human cultures, too, as this passage reveals:

The woodpecker, beating his unique call on a bit of hard, elastic wood, is making an effort, blind and crude enough, but still an effort, to express a musical mood vaguely floating in his nature. We may not laugh at him, so long as from the interior of Africa explorers bring forth the hideous caricatures of musical instruments that some tribes of our own genus delight themselves withal. Among the Southern negroes it was once common to see a dancer going through an intricate terpsichorean score to the music of a “pat,” which was a rhythmical hand-clapping performed by a companion. I mention this in connection with the suggestion that the chief difference between the highest order of bird-music and the lowest order of man-music is expressed by the word rhythm. There is no such an element as the rhythmic beat in any bird-song that I have heard.

WITH WHITE AMERICAN MALE HUMANS AT THE PINNACLE OF CREATION, THEY ARE FREE TO ACT AS THEY SEE FIT TOWARD EVERYTHING ELSE. Thompson certainly allows for the sentiment of care, but in another essay he writes about a day spent in a Southern swamp during which he wasn’t in the mood for shooting anything — as if blasting away at birds was a perfectly reasonable accompaniment to observing them. Try as I will, I cannot appreciate Thompson as a writer — my mind is stuck on the image of him (from his own essay) standing atop a ladder in the deep woods, tearing through the rotten trunk of a tree in order in order to rob a nest of ivory-billed woodpecker eggs “for the sake of knowledge,” only to watch all five of them plummet to the ground by his own klutziness. “The species will probably be extinct within a few years,” he concluded.

AGAIN, I HAVE LITTLE TO SAY ABOUT MY COPY OF THOMPSON’S WORK. The cover is quite impressive, certainly compared to his book of nature essays, “Byways and Bird Notes”, from two years earlier. Otherwise, the book again reveals its age through crumbling binding and yellowed pages, but is without any traces of the journey it has taken to reach me.