May Kellogg Sullivan’s exultation over the coming of spring to northern Alaska is matched by my own notebook comment regarding the same page — “Nature, at last!”. It is page 354 of a book with 392 pages, and it is one of the first (and precious few) passages where Sullivan contributes a few words of description of the natural world. Throughout much of the book, it is the Arctic winter, and Sullivan passes her days knitting clothes for Eskimo children at a mission. Nearly all of the animals she mentions in the book take the form of pelts. For instance, a red fox pelt figures prominently; she had bought it to add to her winter gear, only to have it stolen by one of the several bad elements she encountered during her time in the far north. Her first encounter with a ptarmigan is one that was caught in a trap and was trussed up to be served at dinner.

To be completely fair, the book was a mostly enjoyable read (though the winter knitting scenes did get tedious); it only fails completely when evaluated as a nature book. One thing I learned from reading his volume, and the previous one by Frederick Schwatka, is that a journey to a wild place does not automatically constitute nature writing. May Kellogg Sullivan was not, as far as I can tell, a naturalist of any kind. Her trip to Alaska appears to have been motivated by a quest for gold coupled with some level of interest in adventure. Only once does a proclivity for nature study appear in the work — on page 354. Here it is, in its entirety. Molly was the native wife of the Mission director (called the Captain); Jennie was her semi-invalid daughter.

The last week of May has finally come, and with it real spring weather. The children play out in the sand heap on the south side of the house for hours together, enjoying the warm sunshine and pleasant air, the little girl clothed from head to foot in furs. Never has a springtime been so welcome to me, perhaps because in striking contrast to the long, cold winter through which we have just passed. From the hillside behind the Mission, the snow is slowly disappearing, first from the most exposed spots and rocks, the gullies keeping their drifts and ice longer. Mosses are everywhere peeping cheerfully up at me in all their tints of gorgeous green, some that I found recently being tipped with the daintiest of little red cups. This, with other treasures, I brought in my basket to Jennie when I returned from my daily walk upon the hill, and together we studied them closely under the magnifying glass.

To examine the treasures brought in by Mollie, however, we needed no glass. They are sand-pipers, ptarmigan, squirrels, and occasionally a wild goose, shot, perhaps, in the act of flying over the hunter’s head, as these birds are now often seen and heard going north. In the evening I see from my window the neighboring Eskimo children playing with their sleds, and sometimes they light a bonfire, shouting and chattering in their own unique way. All “mushers” now travel at night when the trail is frozen, as it is too soft in the daytime, and the glare of the sun often causes snow-blindness. Then, too, there is water on the ice in places, which we are glad to see, and pools of the same are standing around the Mission and schoolhouse. I can no longer go out in my muckluks, but must wear my long rubber boots and short skirts.

Today I went out for an hour, walking to Chinik Creek over the tundra, from which the snow has almost disappeared, and returned by the hill-top path. The tundra was beautiful with mosses, birds were singing, and the rushing and roaring of the creek waters fairly made my head swim, they were such unusual sounds. The water was cutting a channel in the sands where it empties into the bay. Here it was flowing over the ice, helping to loosen the edge and allow it to drift out to sea.

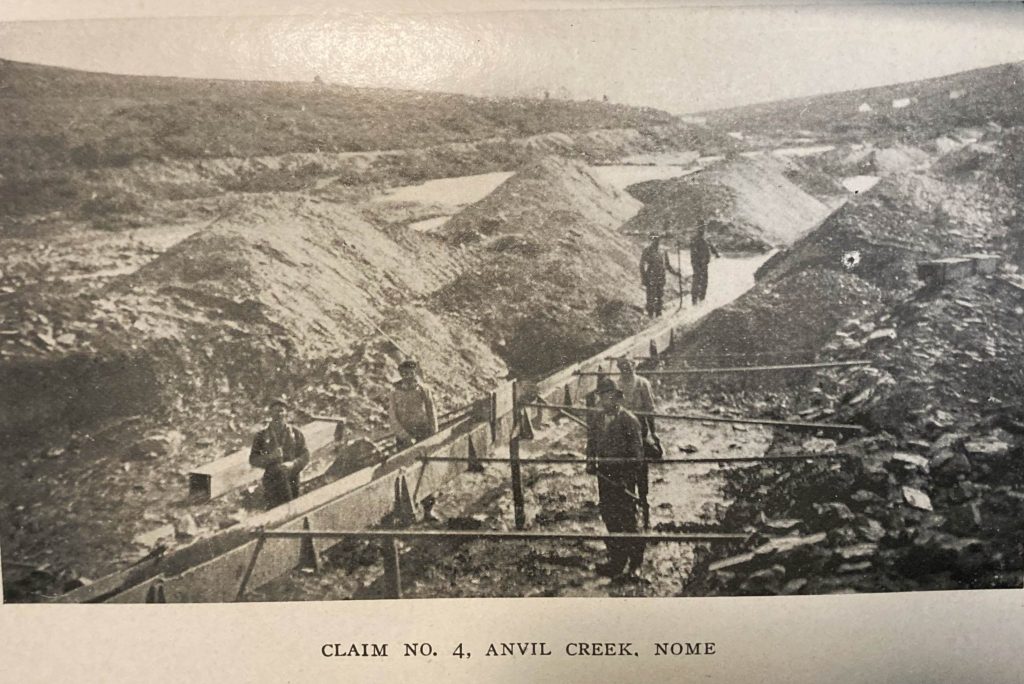

It is, on the whole, a charming springtime tundra scene, though the particular species of birds and mosses are, of course, not provided. How I longed for Sullivan to set out across the tundra and have adventures amongst the various animals of the north — though I suppose the hazard of polar bears would rather discourage that kind of behavior. I struggled throughout the book with wanting it to be what it clearly wasn’t. Where it shines, actually, is in documenting the gritty realities of life in gold rush communities of tents and shacks. Her time in Alaska was chiefly spent in such places, where the thirst for gold was causing considerable environmental harm (which was, of course, overlooked by all). Sullivan’s Kodak camera documents the damage, though.

And yes, this is the Nome gold rush. I had never heard of it before.

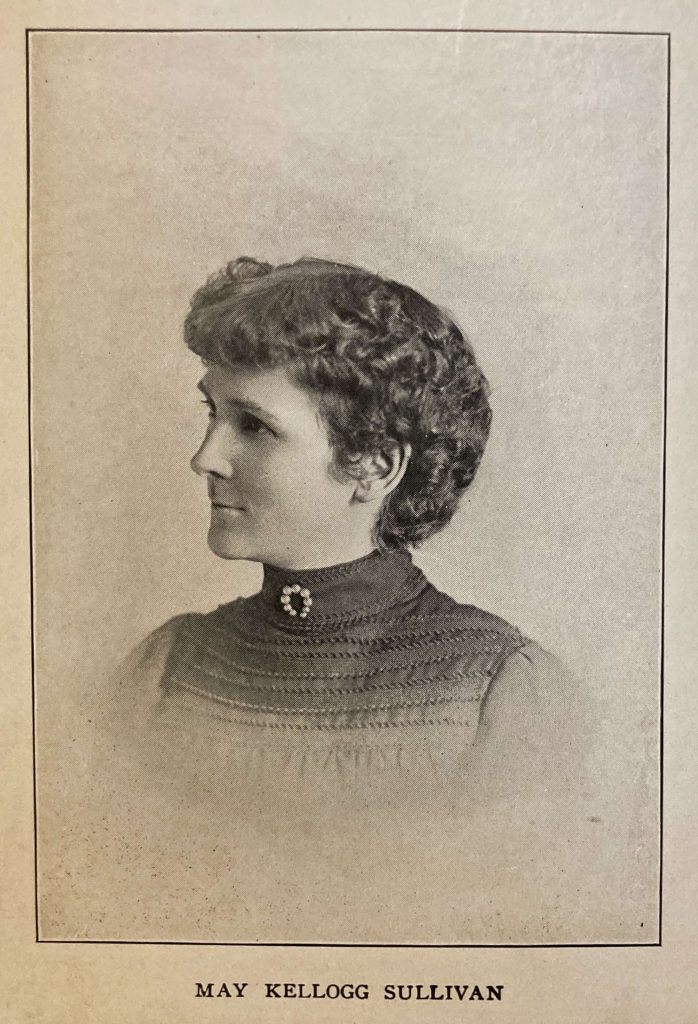

Sullivan herself is a bit of a mystery. I know that she visited Alaska twice over 18 months in 1899-1900, covering over 12,000 miles in her solo travels. She was evidently married at the time but says absolutely nothing about her husband. Were they estranged? Was he deceased? And I have no birth or death dates for Sullivan. She does mention that she is a native of the Badger State, a.k.a., Wisconsin.

I will close out my post with another all-too-brief nature scene, this one from the Arctic summer, soon after Kellogg arrived in Nome (where she got a job in a tent restaurant since women were not permitted to participate in the actual mining work). It is tacked onto a picture of the burgeoning mining camp:

To eyes so unaccustomed as ours to the sight, how strange it all looked at midnight. From the big tent door which faced south and towards Nome City we could see the blue waters of Behring Sea away in the distance. Great ships lying there at anchor, lately arrived from the outside world or just about to leave, laden with treasure, at this long range looked like mere dots on the horizon. Between them and us there straggled over the beach in a westerly direction, a confused group of objects we well knew to be the famous and fast growing camp on the yellow sands. To our right, as well as our left, rolled the softly undulating hills, glowing in tender tints of purples and greys, or, if the moon hung low above our heads, there were warmer and lighter shades which were doubly entrancing.

Accompanying the low moon twinkled the silver stars with their olden time coyness of expression. Little birds, not knowing when to sleep in the endless daylight, hopped among the dewy wild flowers of the tundra, calling to their mates or nestlings, twittering a song appropriate to the time and place because entirely unfamiliar.

My copy of this book is a later edition, from 1915. According to the title page, it is part of the “Thirteenth Thousand” of Kellogg’s work. Given the book’s clear sales success, I am surprised that so little information is available online about its author.