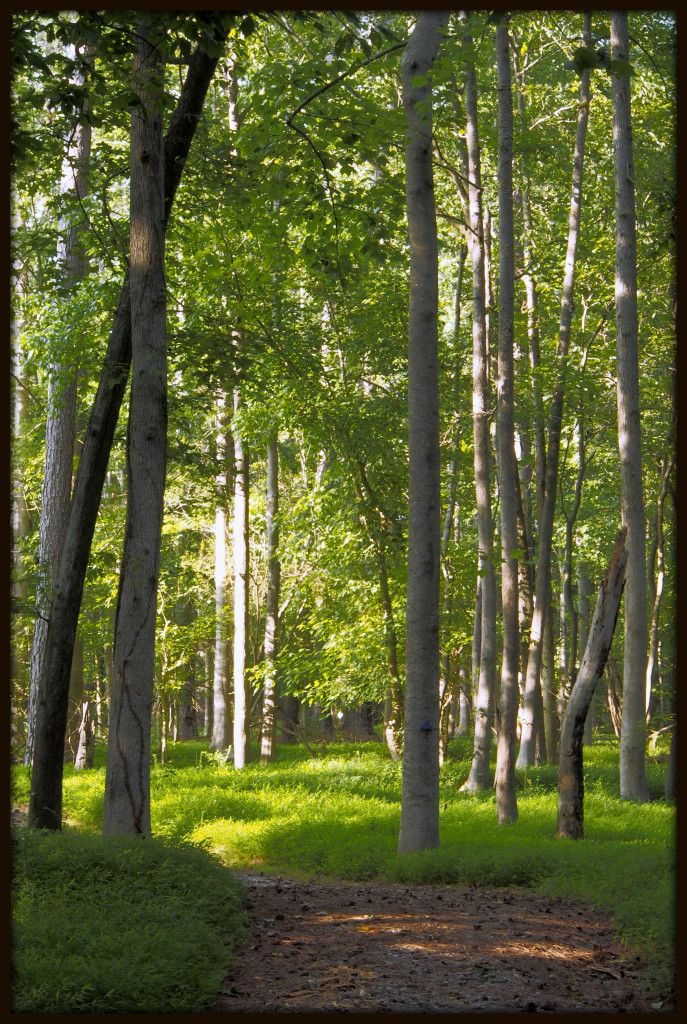

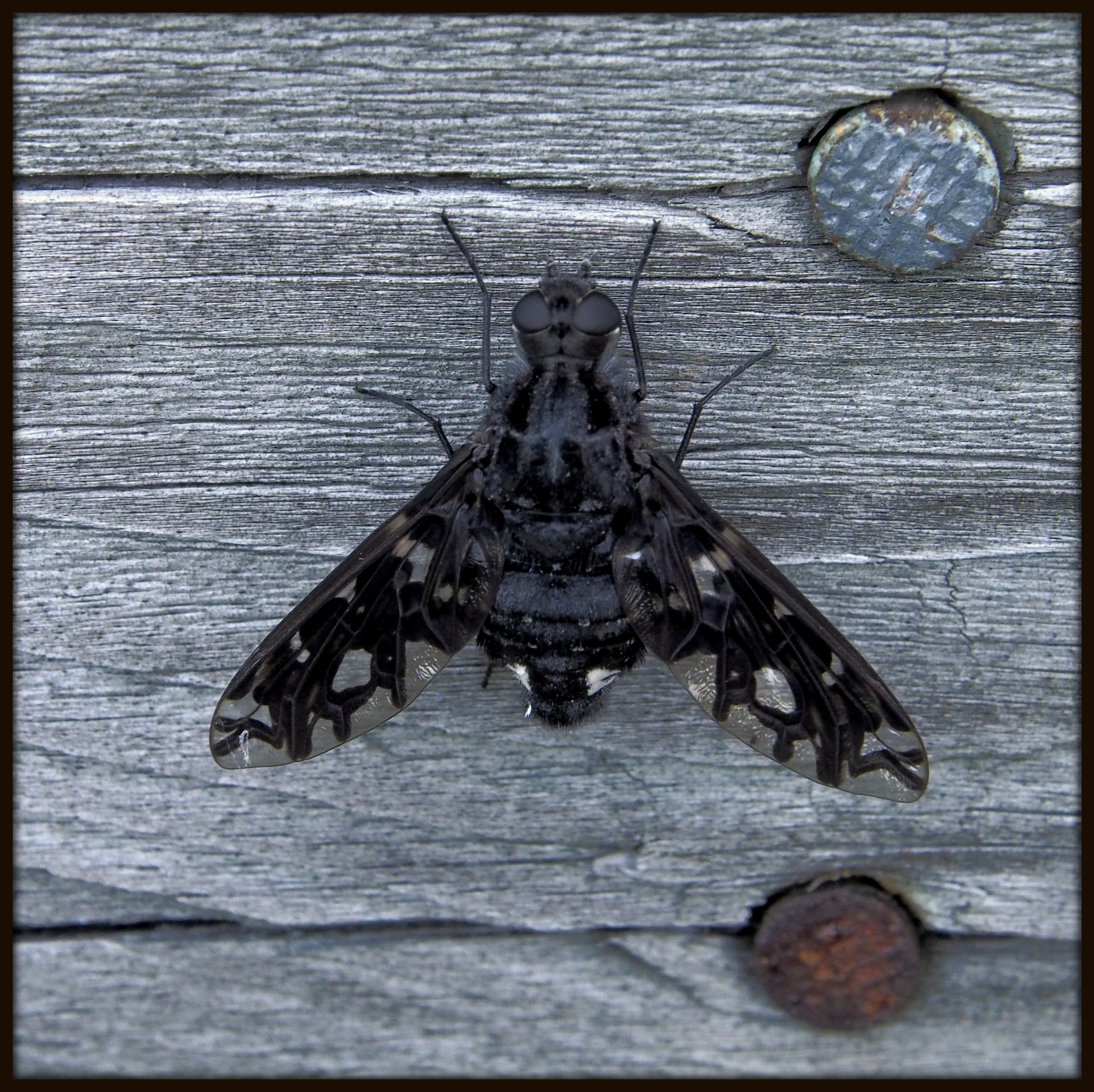

I saw a marvelous image posted on Facebook the other day — a Venn diagram composed of two overlapping circles, one labeled “Science” and the other one “Art”. The intersection region of the two was labeled “Wonder”. Today’s offering from the Examiner archives is a pair of articles about the great blue heron, one from a scientific viewpoint and the other from an artistic one. Both pieces were originally published on June 15, 2010. The left-hand photograph was taken at Sweetwater Creek State Park, Georgia. The right-hand one was taken in White House Beach, a mobile home community on Indian River Bay in Delaware, where my dad was living at the time. He loved watching sunrises and birds from his deck looking out over the open water, I have always share his delight in exploring nature, a trait he encouraged in me from my earliest memories. Gordon F. Blizard, Jr. passed away in December of 2011; this selection from the archives is dedicated to him.

THE GREAT BLUE HERON AS DINOSAUR

From as far back as this writer can recall into his childhood, he has always been entranced by great blue herons. This fascination is due partly, no doubt, to the fact that the great blue heron (Ardea herodias) is an immense bird, standing nearly four feet tall, and with a wingspan of about six feet. As such, it would dwarf all of the songbirds he might see at the backyard feeder though the kitchen window of his Pennsylvania home. But down the street from his home there were ponds and a creek, and from time to time he would glimpse a great blue heron there. It was nearly always in flight over the treetops or along the stream, body long and streamlined, legs tucked behind, wings flapping loudly. Once or twice, it even uttered a call sounding like “FRAWNK”, in a harsh and gutteral voice that seemed to emerge from evolutionary prehistory. For reasons he did not have the words to capture then, but will venture to do so now, the great blue heron has always seemed to belong to the time of the dinosaurs.

One explanation for this image of great blue heron as dinosaur is that, in fact, birds are descended from dinosaurs. The split appears to have taken place about 160 million years ago, when small, two-legged dinosaurs like Velociraptor began to develop feathers. Oddly enough, paleontologists have identified feathered, ground-dwelling dinosaurs, indicating that feathers likely evolved from modified scales before they could be used for flight, perhaps as a means of regulating body temperature or displaying during courtship. The oldest bird fossil is that of Archaeopterix, dating back about 155 million years, an odd mix of avian and reptilian attributes. This early bird may have gotten the worm, but it did so using a mouth containing teeth. It also possessed three separately-clawed fingers and a bony tail. Like later birds, however, Archaeopterix had wings, fused clavicles, and feathers.

So in a sense, perhaps our recognition of great blue herons as being like dinosaurs is an instinctive recognition of their actual kinship. Surely, then, great blue herons must be among the most primitive birds alive today, and therefore closest in relation to dinosaurs? Amazingly enough, scientists doing protein sequencing analysis have concluded that the closest living relative of the dinosaurs, and therefore our closest point of contact with the Mesozoic, is actually a chicken! “Kentucky Fried Dinosaur” jokes aside, then, why does the chicken fail to evoke more than vague thoughts of farm life and possibly soup, while the majestic heron transports this author to the geologic past?

The answer lies, quite possibly, in the great blue heron’s resemblance to a pterosaur. Pterosaurs were an order of reptiles separate from the dinosaurs, which lived throughout the mid to late Mesozoic era (from 220 to 65 million years ago). The first reptiles to take to the air, pterosaurs had hollow bones like birds, and both soared and actively flew on immense membranous wings. Images of a pterodactyl in flight do resemble flying great blue herons. Since pterosaurs evolved about 80 million years before birds split off from the dinosaurs, however, herons and pterosaurs are only distantly related. So the mystery behind the similarity of appearance has to do with the process of convergent evolution, in which two unrelated organisms both evolve similar body forms and structures in order to meet similar environmental requirements. Both have large wingspans and streamlined bodies because those attributes are beneficial for flight.

On the ground, though, any resemblance between pterosaurs and great blue herons quickly vanishes. Tracks of pterosaurs reveal that they were actually quadrupeds, walking on both their hind feet and their wings in a somewhat ungainly manner, possibly as depicted here. While standing in a stream or along the edge of a pond or bay, however, a great blue heron evokes quite different feelings and images for this writer, ones that tend less toward prehistory and more toward poetry. They will be the topic of another article on herons, soon to be written.

THE GREAT BLUE HERON AS POETRY

The great blue heron stands,

Waiting at the water’s edge;

Avian haiku.

There is something about a great blue heron, poised motionless in the shallow waters of a pond, river, or bay, that is profoundly poetic. It gazes outward, waiting for the slightest ripple to betray the presence of a fish. It stands silent, almost blending into the landscape, its long body connecting water and sky. In particular, it evokes haiku, the lean and elemental seventeen syllables of Japanese verse that contains at once both a single instant and the entire universe. Not surprisingly, there is even an online haiku publication called The Heron’s Nest.

The great blue heron’s pose while waiting for a meal has much to teach Westerners. It embodies patience and being in the present moment, waiting for an opportunity to arise rather than trying to make it happen. Just as it awaits the silvery flash of a fish in the shallows, so the poet sits, waiting for words to form themselves into a poem to surface in her consciousness.

The great blue heron also embodies silence and solitude, standing alone against the elements, aloof in the shallows. It may stand in one place for hours, as the sun makes its way across the sky and sets in the west. Approach too closely and it will abruptly take off with a flapping of wings, searching for a place to fish without disruption, further down the coast of the bay or up the river.

The great blue heron is not always a bird of stillness, though. Indeed, despite the haiku publication title, the heron’s nest can be quite a raucus place. Herons build their nests of sticks lined with reeds, mosses, and grasses high in the trees in wet, forested areas. They nest in dense colonies called rookeries, which can be both smelly (from the abundant bird droppings) and loud (from many squawking birds). As herons return to a rookery year after year, eventually their tree stand is killed off, forcing the birds outward, leaving a bulls-eye pattern with a central core of dead trees and an outer ring of nest trees that are slowly dying. In these nest areas, great blue herons take on a nearly opposite personality to that of the quiet fishers that they appear to be at other times in the year. At the rookeries, herons are loud, argumentative, and destructive. But perhaps the aspects of great blue heron behavior encountered in a rookery might be viewed as a necessity. Maybe their nesting behavior is required in order to balance out their other, more poetic, solitary and silent selves.