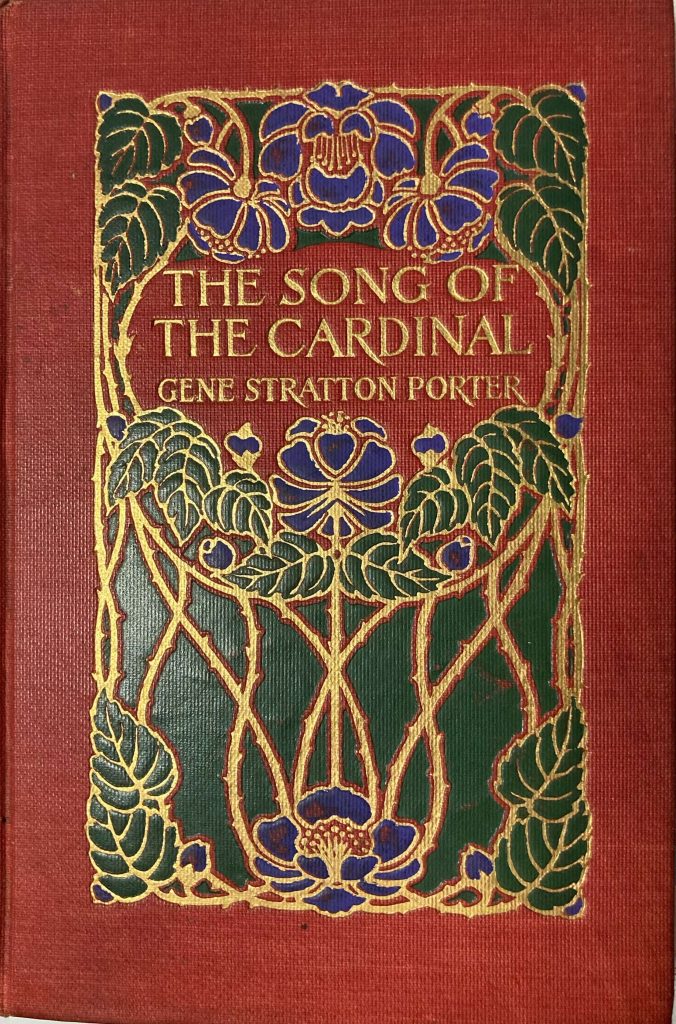

Gene Stratton Porter (1863-1924) was 40 when The Song of the Cardinal was published. Her first book, it was the start of a long lineage of works, primarily fiction, extolling the wonders of the natural world. Though it tells a story (in a manner of speaking), along the way, The Song of the Cardinal offers a rich tapestry of Edenic landscapes, including both an orange grove in Florida and Limberlost Swamp and a farm along the banks of the Wabash River in Indiana. The 1912 edition that I read (a copy of which is housed in the collections of The Met in NYC) is graced by a truly magnificent art nouveau cover attributed to Margaret Armstrong. Armstrong (1867-1944) was one of the premier artists of the golden age of book design. A year after this book was published, Armstrong left the cover design field to write her own books: first an illustrated wildflower guide for the Western US, then biographies and mystery novels.

Most of the book is told from the viewpoint of a male Cardinal, as he returns north for the spring and struggles to attract a mate. Humans briefly appear on the scene — an old man and his daughter in the orange grove — then vanish from the story. Later, the reader meets 60-year-old Abram and his wife Maria, a farming couple growing corn and keeping chickens along the Wabash River in Indiana. From that point forward, the book alternates between their rustic dialogue and the viewpoint of the cardinal. Throughout the book, nature is really the central character. Early on, Porter introduces us to the glories of Limberlost Swamp:

Three thousands of acres of black marsh-much stretch under summers’ sun and winters’ snws. There are darksome pools of murky water, bits of swale and high morass. Giants of the forest reach skyward, or, coated with velvet slime, lie decaying in sun-flecked pools, while the underbrush is almost impenetrable.

The swamp resembles a big dining table for the birds. Wild grape vines clamber to the tops of the highest trees, spreading umbrella-like over the banches, and their festooned floating trailers wave like silken fringe in the play of the wind. The birds loll in the shade, peel bark, gather dried curlers for nest material, and feast on the pungent fruit. They chatter in swarms over the wild-cherry trees, and overload their crops with red haws, wild plums, pawpaws, blackberries and mandrake. The alders around the edge draw flocks in search of berries, and the marsh grasses and weeds are weighted with seed hunters. The muck is alive with worms; and the whole swamp ablaze with flowers, whose colors and perfumes attract myriads of insects and butterflies.

Although the male cardinal in this story fledged there and first returned there after his winter in the south, ultimately he abandons Limberlost for a bucolic farm and woodland along the Wabash River, home of Abram and Maria. “To my mind,” Abram declares to the cardinal (whom he greets as Mr. Redbird), “it’s jest as near Paradise as you’ll strike on earth.”

Old Wabash is a twister for curvin’ and windin’ round, an’ it’s limestone bed half the way, an’ the water’s as pretty an’ clear as in Maria’s springhouse. An’ as for trimmin’, why say, Mr. Redbird, I’ll just leave it t you if she ain’t all trimmed up like a woman’s spring bonnit. Look at that grass a-creepin’ right dwn till it’ a-trailin’ in the water! Did you ever see jest quite such fie frigy willers? An’ you wait a little, an’ the flowerin’ mallows ‘at grows long the shinin’ old river are fine as garden hollyhocks. Maria says ‘at they’d be purtier ‘an hurs if they wer eonly double; but, lord, Mr. Redbird, they are! See ’em once on the bak, an’ agin in the water! An’ back a little an’ there’s jest thickets of pawpaw, an’ thorns, an’ wild grapevines, an’ crab, an’ red an’ black haw, an’ dogwod, an’ sumac, an’ spicebush, an’ trees! Lord! Mr. Redbird, the sycamrs, an’ maples, an’ tulip, an’ ash, an’ elm rees are so bustin’ fine ‘long the old Wabash they put ’em in poetry books an’ sing songs about ’em. What do you think of that? Jest back o’ you a little there’s a sycamore split into five trunks, any one of them a famous big tree, tops up ‘mong the cluds, an’ roots diggin’ under the old river; an’ over a little further ‘s a maple ‘at’s eight big trees in one. Most anything you can name, you can find it ‘long the old Wabash, if you only know where to hunt for it.

To her credit, while Gene Stratton Porter describes her Indiana natural landscapes in Edenic terms, that does not mean that the wolf lies with the lamb and the leopard lays down with the kid. There is predation and death; for instance, a cardinal chick falling into the water is at once snatched up by a mackerel. And the birds, for all their lovely songs, do not all behave in considerate ways toward each other. Indeed, Porter uses a pair of woodpeckers nesting in a sycamore tree to portray domestic abuse, long before that was a topic for everyday conversation:

…the woodpecker had dressed his suit in finest style, and with dulcet tones and melting tenderness had gone a-courting. Sweet as the dove’s had been his wooing…yet scarcely had his plump, amiable little mate consented to his caresses and approved the sycamore, before he turned on her, pecked her severely, and pulled a tuft of plumage from her breast. There was not the least excuse for this tyrranical action; and the sight filled the Cardinal with rage. He fully expected to see Madam Woodpecker divorce herself and flee her new home, and he most earnestly hoped that she would; but she did no such thing. She meekly flattened her feathers, hurried work in a lively manner, and tried in every way to anticipate and avert her mate’s displeasure. Under this treatment he grew more abusive, and now Madam Woodpecker dodged every time she came within his reach.

The woodpecker is one of the exceptions, though. On the whole, the natural world in Porter’s tale tends to be filled largely with flowers and birdsong. The true serpent in this paradise is Man the Hunter. It is he who threatens to disrupt the pastoral tranquility, wantonly killing birds and other wildlife. Abram attempts to protect the cardinal and all the other birds on his farm by posting “No Hunting” signs, explaining that

…them town creatures…call themselves sportsmen, an’ kill a hummi’ bird to see if they can hit it. Time was when trees an’ underbrush were full o’ birds an’ squirrels, any amount o’ rabbits, an’ the fish fairly crowdin’ in the river. I used to kill all the quail an’ wild turkeys about here to make an appetizing change. It was always my plan to take a little an’ leave a little. But just look at it now. Surprise o’ my life if I get a two-pound bass. Wild turkey gobblin’ would scare me out o’ my senses, an’, as for the birds, there are just about a fourth what there used to be, an’ the crops eaten to pay for it.

Here, Abram’s complaints seem hauntingly familiar, as scientists continue to report on the decline of songbirds across the US. Of course, the signs prove insufficient. Abram observes a hunter walking down his lane and confronts him. The hunter claims to be merely passing through, and Abram lets him continue. Before Abram can stop him, the hunter has fired at the cardinal in a sumac tree, fortunately missing him completely. Abram arrives in time to prevent any killing, launching into a several-page impassioned tirade about needing to protect the natural world. I wonder if the entire book, with its minimal narrative, was intended primarily as a vehicle for sentiments such as these:

Sky over your head, earth under foot, trees around you, an’ river there, — all full o’ life ‘at you ain’t no mortal right to touch, ‘cos God made it, an’ it’s His! Course, I know ‘at he said distinct ‘at man was to have “dominion over the beasts o’ the field, an’ the fowls o’ the air.” An’ ‘at means ‘at you’re free to smash a copper-head instead of letting it sting you. Means at’ you better shoot a wolf than to let it carry off your lambs. Means ‘at its right to kill a hawk an’ save your chickens; but God knows ‘at shootin’ a redbird just to see the feathers fly isn’t having dominion over anything; it’s just makin’ a plumb beast o’ yourself.

Alas, Porter’s concern for wildlife included a number of exceptions that would make the modern-day environmentalist cringe. Still, Porter’s central argument stands: humans need to protect other beings, because they have a spiritual origin. Ultimately, caring for God’s creation is more than just a Biblical obligation in Porter’s mind; it is a profoundly religious act. As Abram explains (further along in the same tirade, while the hunter stands mute):

To my mind, ain’t no better way to love an’ worship God, ‘an to protect an’ ‘preciate these fine gifts he’s given for our joy an’ use. Worshippin’ that bird’s a kind o’ religion with me. Getting the beauty from the sky, an’ the trees, ‘an the grass, ‘an the water that God made, is nothin’ but doin’ him homage. Whole earth’s a sanctuary. You can worship from sky above to grass underfoot.

Finally, the hunter, reduced to jelly by the farmer’s words (either their intent, or merely their duration) pleads for forgiveness, abandons his gun to Abram’s keeping, and flees, declaring that “I’ll never kill another harmless thing.” Summer ends, and with the autumn, the cardinal and his brood take flight for the orange grove in Florida, bringing the book full circle.

As a work of literature, Porter’s Song of the Cardinal has faded into fitting obscurity; the story simply doesn’t manage to live up to its cover (at least, not the 1912 art nouveau one). Very little happens in the tale, and what does occur is either highly predictable or rather silly. Yet there is poetry in Porter’s rich descriptions, along with a wealth of firsthand knowledge of the plants and animals of her native state, gleaned from many years of fieldwork in the swamps, fields, and woods around her homes (she had a house on Sylvan Lake in Rome City, and a cabin on the edge of Limberlost Swamp). And the passionate call for better treatment of wildlife, so vital at the time, qualifies her as an early member of the American environmental movement. Her fascination with birds would continue long beyond this book, in her early wildlife photography efforts documented in non-fiction works published later in her life. She also wrote (and illustrated with photos) a guide to the moths of the Limberlost. I have secured copies of these books and will devote posts to them at some point in the future.

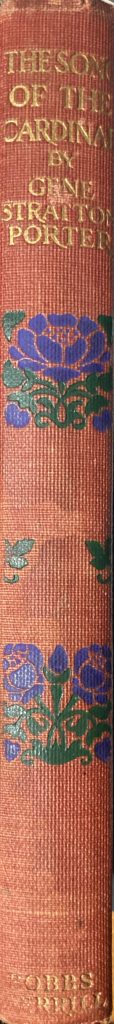

As I noted a the beginning of this post, I preferentially sought out the 1912 edition of this book (rather than a 1903 first edition) because of its spectacular cover. The artwork on this spine, though, is a bit, well, odd. Apparently the spine was stamped upside down. So rather than displaying the title with flowers above and below it, the title stands by itself at the top of the spine, with flowers bracketing bare cloth further down. From what I was able to find out online, the remaining copies of this edition appear equally split between the correct stamping of the spine and this alternative (accidental) one.

My book was previously the property of Mary S. Jones of Fairfield, Alabama; her name (printed in blue ink) and a return address sticker are found on the flyleaf. The sticker looks more recent than the actual book. I was unable to locate any information about Mary S. Jones, though the task was made difficult by her rather common last name.