WHEN THOMAS WILSON FLAGG DROPPED HIS FIRST NAME EARLY IN HIS WRITING CAREER, IT WAS HIS FIRST AND LAST ACT AS EDITOR. What would follow, over the course of a lengthy and prolific writing career, would be dozens and dozens of highly detailed accounts of nature — birds, trees, the functions of a forest. What they nearly all share is a writing style that one admiring reader called “whimsical” but I would classify instead as soporific. I will allow the modern-day reader to judge from this supposedly “whimsical” passage:

Evening calls [the botanist] out from his retreat, to pursue another varied journey among the fairy realms of vegetation, and ere she parts with him curtains the heavens with splendor and prompts her choir of sylvan warblers to salute him with their vespers.

Another example, the inspiration for the title of this post:

The White Cedar constitutes with the southern cypress the principal timber of the Great Dismal Swamp, and is the last tree, except the red maple, which is discovered when travelling through an extensive morass.

FLAGG IS NOTABLE TODAY CHIEFLY FOR BEING A CONTEMPORARY OF HENRY THOREAU, RECOGNIZING THOREAU, GEORGE PERKINS MARSH, AND JOHN BURROUGHS AS SOURCES OF INSPIRATION. Alas, he and Thoreau never met (nor did he meet the the other two, from what I have found). However, in an 1857 letter to Daniel Rickerson, Thoreau voiced his opinion of Flagg’s work in no uncertain terms; after reading 300 pages of Flagg’s writing, I honestly confess that I agree with Thoreau on this one:

Your Wilson Flagg seems a serious person, and it is encouraging to recognize a contemporary who recognizes nature so squarely…. But he is not alert enough. He wants stirring up with a pole…. His style, as I remember, is singularly vague (I refer to the book) and before I got to the end of the sentences I was off the track.

TO BE FAIR TO FLAGG, THE BOOK I READ PUTS HIM AT A CONSIDERABLE DISADVANTAGE FOR WINNING OVER THE READER. During his lifetime, he produced dozens of essays, and all of his books are essay compilations. One of them followed the year round, making use of an organizational structure that was commonly employed from the 1840s through the 1940s, and is still encountered in some modern-day nature writing. The one I read — the only volume I could afford, I might add, due (I expect) to the relative scarcity of the other tiles — was “A Year Among the Trees”. It consists of a subset of essays, taken from a larger work, “The Woods and Byways of New England”. The common theme in this work is trees and shrubs. Unfortunately, most of the essays highlight particular tree and shrub species, giving them a rather field-guidish treatment but often without illustrations and without scientific names in the text (though they are included in the table of contents). Flag tends to focus his account on aesthetic considerations, highlighting the degree to which a tree form is picturesque or not, and the extent to which the tree is more or less attractive than its English counterpart (when there is one). Combine that with wandering sentences generally long on Latinate words, and the result is a sort of mind-numbing tedium, a morass of tree limbs, leaf forms, and flowery words.

THERE IS ANOTHER KIND OF ESSAY IN THIS BOOK, TOO; IT INCLUDES SOME OF HIS FINEST WORK AND ALSO SOME OF HIS MOST PECULIAR IDEAS. In a series of essays scattered throughout the book (with no clear order to them), Flagg explores the nature and functions of forests. The volume opens with an essay on The Primitive Forest in which Flagg proposes that, prior to European settlement, most of North America east of “The Great American Desert” (as the Great Plains was called at the time) was densely covered with forest. Subsequent clearing of the trees has led to regional warming, for reasons explained here:

The American climate is now in that transitional state which has been caused by opening the space to the winds from all quarters by operations which have not yet been carried to their extreme limit. These changes of the surface have probably increased the mean annual temperature of the whole country by permitting the direct rays of the sun to act upon a wider area….

WHILE HIS CLIMATOLOGICAL SPECULATIONS FELL WIDE OF THE MARK, HIS CONCERNS ABOUT THE LOGGING OF STEEP SLOPES REMAIN SCIENTIFICALLY VALID. As in his thoughts about the influence of forest cover on climate, it is not clear the extent to which Flagg’s ideas are original; in this case, for instance, he may owe a debt to George Perkins Marsh (who he mentions in another essay in the book). In his essay Relations of Trees to Water, Flagg explains,

If each owner of land would keep all his hills and declivities, and all slopes that contain only a thin deposit of soil or a quarry, covered with forest, he would lessen his local inundations from vernal thaws and summer rains. Such a covering of wood tends to equalize the moisture that is distributed over the land, causing it, when showered upon the hills, to be retained by the mechanical action of the trees and their undergrowth of shrubs and herbaceous plants, and by the spongy surface of the soil underneath them, made porous by mosses, decayed leaves, and other debris, so that the plains and valleys have a moderate oozing supply of moisture for a long time after every shower. Without this covering, the water when precipitated upon the slopes, would immediately rush down over an unprotected surface in torrents upon the space below.

AS AN AMATEUR GEOMORPHOLOGIST, FLAGG IS QUITE NOTEWORTHY. Indeed, his musings remind me of some of Thoreau’s own unpublished research and observations on the effects of dams on stream flow. Like Thoreau, Flagg looked closely and thought deeply about natural processes in his native Massachusetts. Also like Thoreau, he calls for the establishment of parks to protect the remaining New England forests. First, here is Thoreau, from the last pages of his manuscript “Wild Fruits” as edited by Bradley Dean:

I think that each town should have a park, or rather primitive forest, of five hundred or a thousand acres…where a stick should never be cut for fuel, nor for the navy, nor to make wagons, but stand and decay for higher uses — a common possession forever, for instruction and recreation.

And here is Wilson Flagg’s proposal, from his essay The Dark Plains; though not quite as plainly spoken, he echoes Thoreau’s general sentiment well:

Some spacious wood ought to remain, in every region, in which the wild animals would be protected, and we might view the grounds as they appeared when the wild Indian was lord of this continent.

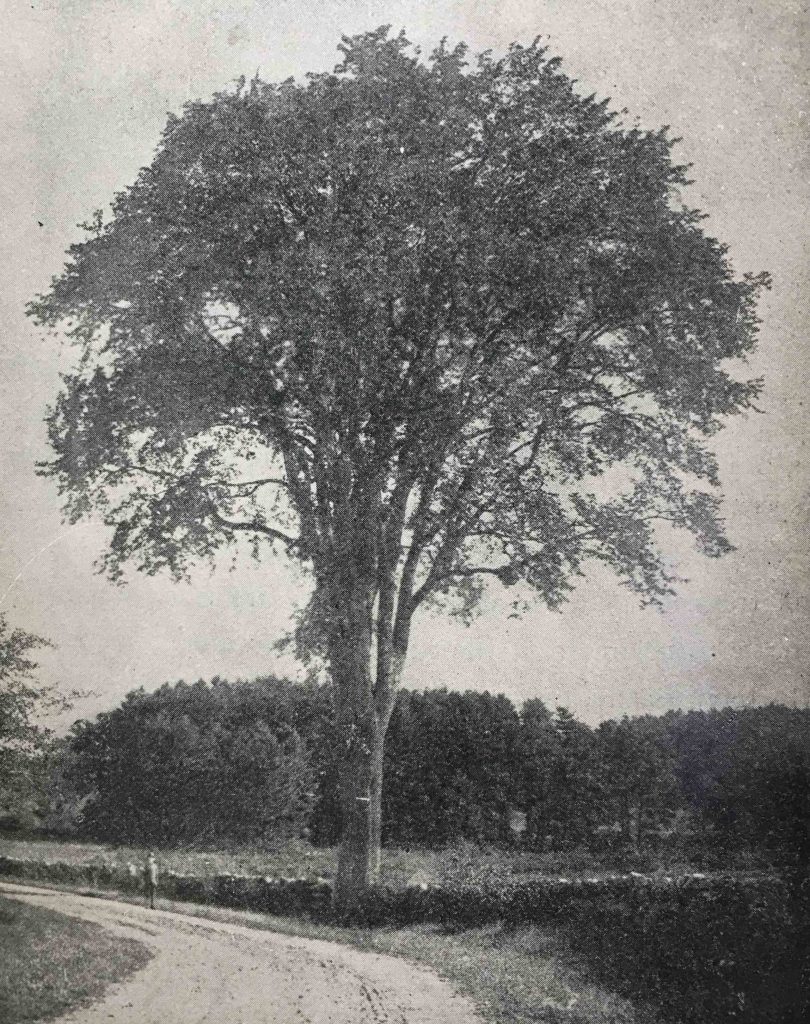

FINALLY, A FEW WORDS ABOUT MY BOOK ITSELF. This time, the closest I could come to an original volume by the author was an edition of Flagg from 1889, eight years after the original edition, and five years after Flagg’s death. Apart from the gilt cover with pine branch and cones, the book is fairly nondescript. The work includes three photo illustrations, including the roadside elm above. It also includes a number of line drawings of the parts of various trees and shrubs. Affixed to the inside of the front cover is a book label, indicating this book was once part of the Private Library of Walter S. Athearn. Here my tale potentially gets more interesting. Out of curiosity, I did a Google search of the name, and this biography turned up. Dr. Walter Scott Athearn lived from 1872 until 1934, and was a pioneering religious educator. While much of his life was spent in Iowa, he did move east in 1916 to serve for 13 years as a Graduate School Dean at Boston University. Could he have purchased the title in some used bookshop upon his arrival, perhaps with an eye toward learning more about the trees and forests of his new home state? Or could the person who owned my book just happened to have had the same name? I could not locate any obituaries online for a different Walter S. Athearn, but I doubt I will ever know for certain. Meanwhile, his photo brings a fitting closure to this post.