Effie Molt Bignell is one of those most unusual personages, an author who does not even have a Wikipedia page to her name. I was able to glean from a few bits and pieces online that she was born in 1855 in Burlington, Vermont. A member of the American Ornithological Union, she authored several books, including two with a nature focus: Mr. Chupes and Miss Jenny (about two robins) and this one. She married William J. Bignell. That is all that I know about her. I cannot even locate her picture. I might add that my information search was impeded a bit by the title of this book, which tended to yield Google results such as this one:

No, this is not THAT kind of book! In fact, it is a flowing, charming romp through a wooded grove and adjacent gardens belonging to an obviously wealthy woman with abundant time on her hands. As she describes in the book, her home is quite large, with a carriage drive in the front, and employing at least one maid and gardener. Her aristocratic bearing is telegraphed to readers through her occasional cultured French phrases (untranslated, of course) such as feu-de-joie, haute société, and table d’hôte. With the exception of the last chapter (a trip to a rural community near the St. Lawrence River in Quebec), the book entirely takes place, over the course of a year, on Effie Bignell’s estate somewhere in eastern New Jersey. There, she entertains the reader as an honored guest, telling stories about the birds and squirrels of her domain, and pointing ut the various seasonal sights of her woods. I admit that I found her companionship in text quite affable, her descriptions vivid and poetic. There is no particular storyline or grand adventure. There is, though, a bit of escape into an affluent suburban yard of more than 100 years ago. Her hope, in writing this work, was that “to someone in sick room or city pent, these pages might carry restful little messages from “God’s out-of-doors,” or pleasing suggestions of woodland friends.” At the close of the volume, I confess that I was sorry to part company with the author, as she remarked on the journeys we had taken together:

Do you realize that nearly a twelvemonth had elapsed since you and I took our first stroll through the grove together? How rapidly the “mounds of years” heap themselves up! How quickly the cycles pass! Oh, for unlimited leisure, for unbounded opportunities for investigation, and the vision that penetrates to the heart of the mysteries by which we are surrounded.

In-between preface and closing line, seasons change, but otherwise precious little happens. There are no grand ecological discoveries, spectacular events, profound statements, or even “walks afield” (at least, until the final chapter). There is the house and the yard and the trees. Yet her flowing imagery carries the reader along, and her childlike delight in nature is quite enticing. Consider this lovely, languid description of a summer afternoon:

The noonday lull has already set in. No sound now save the bees’ drowsy droning and the rustling of wind-swayed leaves. In the wild garden daisies and buttercups are nodding to each other, and soft waves and ripples are playing over the tops of the tall grasses. How caressing, how soothing the fragrance-laden breeze as it fans one’s brow and lightly touches one’s hair, whispering all the time of beautiful, mystical things to which the heart responds though it but dimly understands.

The reader is overcome with this desire to pull up a lounge chair and take it all in. Heck, in her world, even decaying leaves are worthy of appreciation, as she relates below in her chapter Good-by to Summer:

Several bird families have already left us, and others are on the eve of departure. In this beautiful secluded corner a pair of wood-thrushes have held a perpetual At Home from early in the season. It is just the wild, unmolested spot to take the fancy of those ardent wood-lovers. Broken boughs have piled themselves up undisturbed under the interlocking branches from which they fell, and moist, rich leaf-mold, boasting of layers and layers, generaions and generations of decay, mats itself around the deeply shaded tree-bases. Think of the lucious larder this represents!

Along the way, Bignell gently nudges readers toward taking action on behalf of songbirds. She shares tips for feeding birds in the winter and reminds readers about how much plant and tree destruction by insects is prevented by the work of birds. Like many writers of the time, she is clearly quite taken with her avian visitors. At one point, she fervently declares,

What wonderful beings birds are! Earth, tree-tops, and sky are at their service, and, for some of their number, even surging waves make a safe resting-place and deep snows a warm covering. How pitiful and small and labored do even the swiftest and most extensive of our voyages seem in comparison with the free, untrammelled journeyings of these “brothers of the air”.

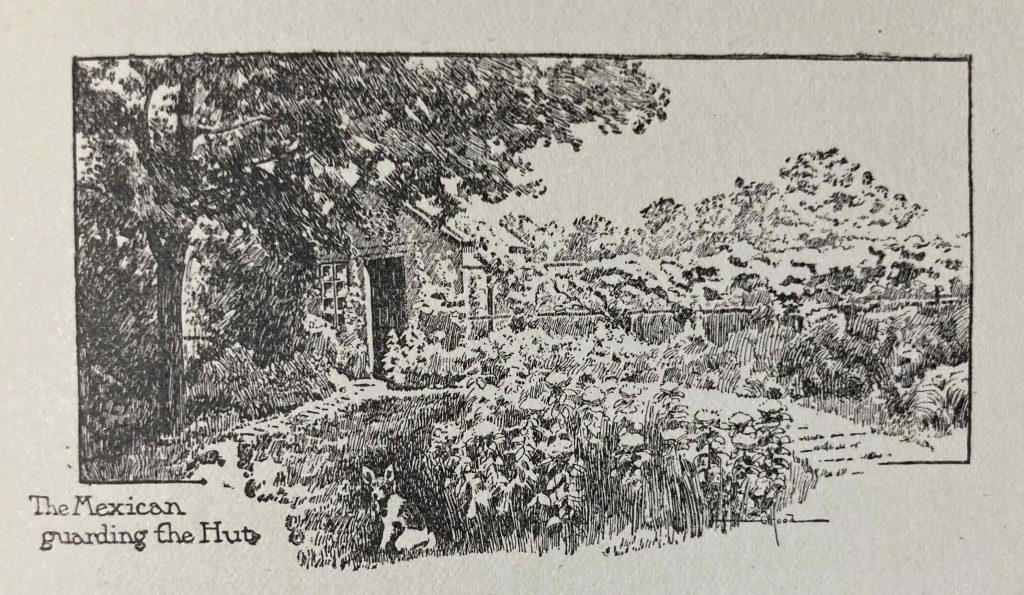

Apart from all the birds (lots and lots of them, calling from practically every page) and a few squirrels (named, of course), the only other character in Bignell’s book is her dog, “a vigilant little Chihuahuan” also known as “The Mexican”. A feisty protector of birds, she patrols the area where Bignell puts out seeds, nuts, and breadcrumbs for the birds, making sure that the birds can dine without putting their lives at risk. “Such is the power of valor,” Bignell declares, “that all the cats of the neighborhood flee in terror before the redoubtable little creature; three pounds and a half of dog!”

Reluctantly, I close the book. Another half-dozen titles arrived today, continuing to build my library of obscure American nature authors from 100 years ago or more. Other volumes and authors are jostling me for attention. Yet I hold this book — completely free of marks from past owners — in my hands for a moment longer. It feels light, smooth, and comfortable. Maybe I’ll visit again someday…