I return to Torrey as an old friend of long acquaintance. The inspiration behind the blog was the discovery of an early compilation of nature writers, which included extensive work by Thoreau, several essays of Burroughs, and a few pieces each by Bradford Torrey, Dallas Lore Sharp, and Olive Thorne Miller. All three were fairly renowned in their day, publishing extensively in the nature essay genre, particularly ornithological pieces. And all three are nearly forgotten today — so they join the inevitable company of a host of other obscure authors who never managed to achieve much fame. Was I to read all the books the three together wrote, that would take me the better part of a year. Still, I have decided to explore several works by each to gain a richer sense of how they encountered the natural world.

According to the scanty lines on him in Wikipedia, Torrey lived from 1843 until 1912. He is known today mainly as an ornithologist. He frequently contributed to periodicals, compiling his published essays into nine books. The Foot-Path Way was his third work. The first half of the book is given over to travel essays — works where Torrey ventures afield and reports on all the birds he has seen (or not seen). His ramblings take him to Cape Cod, northern New Hampshire, and Mount Mansfield, Massachusetts. His descriptions are fairly dry, a point to which he alludes upon occasion. Here, Torrey laments how rare it is that he truly rhapsodizes on the beauty of nature:

So it is with our appreciation of natural beauty. We are always in its presence, but only on rare occasions are our eyes annointed to see it. Such ecstasies, it seems, are not for every day. Sometimes I fear they grow less frequent as we grow older.

We will hope for better things; but, should the gloomy prognostication fall true, we will but betake ourselves the more assiduously to lesser pleasures, — to warbers and willows, roses and strawberries. Science will never fail us. If worse comes to worst, we will not despise the moths.

In a later essay in the volume, on the passing of birds overhead during the autumn migration, Torrey remarks upon a screech-owl he has frequently observed sitting atop a tall tree: “More than half the time he is there, and always with his eye on me. What an air he has! — like a judge on the bench! If I were half as wise as he looks, these essays of mine would never more be dull.”

The second half of the book is predominantly bird studies: essays where Torrey seeks answers to questions about bird behavior through his detailed observations and occasional anecdotes from others. For example, he explores whether or not male ruby-throated hummingbirds assist the females with incubating the eggs or raising their young. (He concludes that he suspects not, but that he is not convinced one way or the other; scientists now know that males only remain with the females for courtship and mating.) He also explores roosting behavior among American robins (which appears to be limited to young birds and unmated males). He notes the seasonal passage of long numbers of songbirds overhead, many too high up to see with the naked eye — much larger numbers than we would likely experience today. He freely confesses his fascination with birds: “A happy man is the bird-lover; always another species to look for, another mystery to solve.” That said, Torrey attributes personhood to birds, asserting that “Birds and men are alike parts of nature, having many things in common not only with each other, but with every form of animate existence.” Studying birds, therefore, can ultimately teach us about ourselves: “To become acquainted with the peculiarities of plants or birds is to increase one’s knowledge of beings of his own sort.”

More, still, might be gleaned from plants if we only knew how to interpret them. In one essay, Torrey considered similarities between plants and people; alas, he restricted himself to analogous ones, such as how roses with thorns mirror lovely people with a few uncommendable qualities. If only he had wondered more about plant behavior, he might have been far ahead of his time. The last essay is a brief paean to the white pine (which Torrey prefers to call the Weymouth pine). In one of his most poetic passages in the book, he writes about the pine’s mysterious communications:

…the pine is a priest of the true religion. It speaks never of itself, never its own words. Silent it stands till the Spirit breathes upon it. Then all its innumerable leaves awake and speak as they are moved… …the pine tree, under the visitation of the heavenly influence, utters things incommunicable; it whispers to us of things we have never said and never can say, — things that lie deeper than words, deeper than thought. Blessed are our ears if we hear, for the message is not to be understood by every comer, nor, indeed, by any, except at happy moments. In this temple all hearing is given by inspiration, for which reason the pine-tree’s language is inarticulate, as Jesus spake in parables.

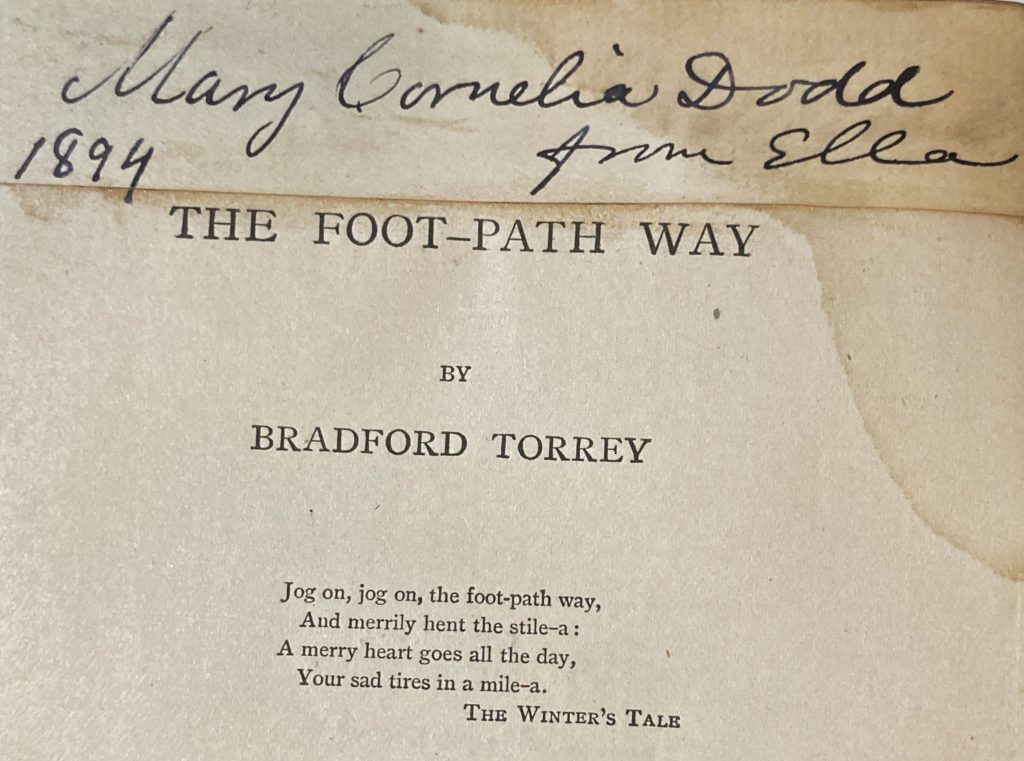

My well-worn copy of Torrey’s book has had quite a history. It appears to have been given to Mary Cornelia Dodd by Ella in 1894. I managed to locate information on several Mary C. Dodds, living and deceased, but none whose life trajectories quite fit this one. There was a Mary C. Dodd who was born in Arkansas in 1973, and would have been 21 in 1894; however, she married John Archie Fain in 1891 and would likely have taken his last name, in keeping with traditions at the time.

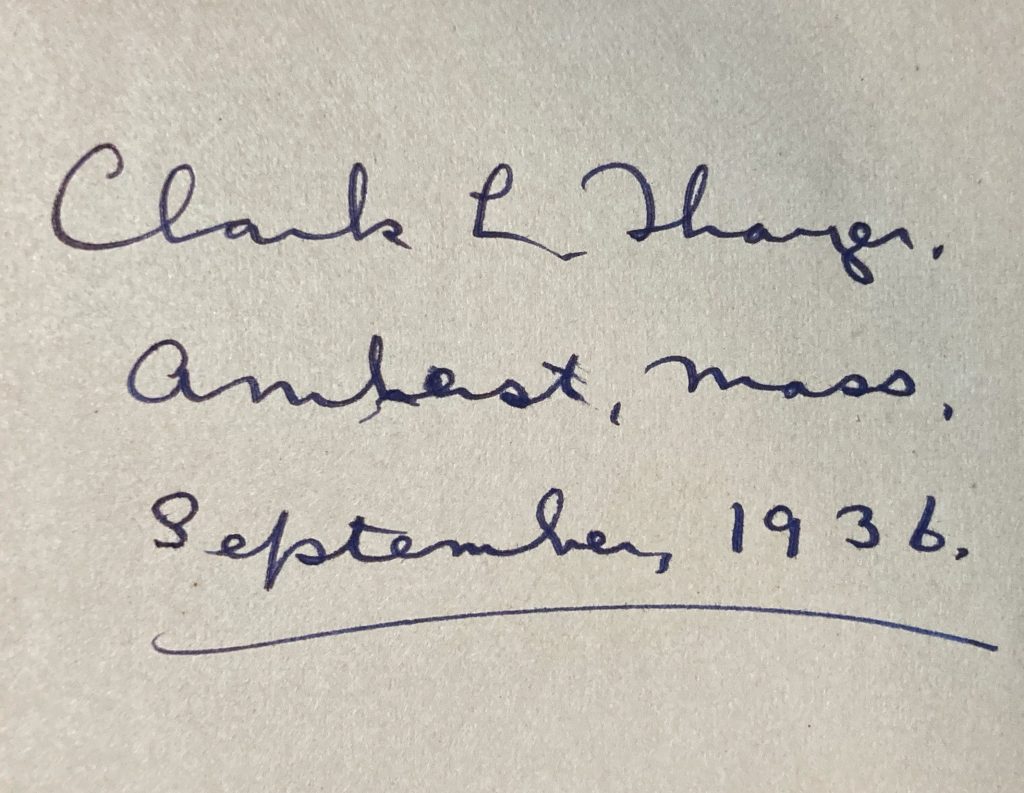

The book found its way into the possession of Clark L. Thayer of Amherst, Massachusetts, in September 1936. Here, I was surprised to find a likely owner: Clark Leonard Thayer, who graduated from UMass Amherst in 1913, with a degree in Floriculture. In World War I, Thayer served in the Infantry and Ammunition Train. After the war, he became an instructor in Floriculture at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. In 1928, he published Spring Flowering Bulbs: Hardy and Desirable Materials for Use in the Home Garden. At some point before 1936, Thayer relocated to Amherst, probably to teach there. He died in 1982 at the age of 91 in Amesbury, Massachusetts, and is buried in Quabbin Park Cemetery in Ware, Massachusetts.

The final “signature” is an herbal tea stain visible on Mary Dodd’s signature. That was the work of Evil Kitten, our mischievous black cat. By jumping at precisely the right angle onto a low bookshelf at the foot of the bed, he managed to knock a half-glass of tea onto the bed itself, where this book conveniently happened to be sitting a the time.