If we are seeking God in nature, we shall not find him so readily by analysis as by synthesis; not by minute study of individuals and par ticulars, but by free, joyous acceptance of the effect of nature as a whole. So, I think, we shall be justified in leaving our note books at home in September, and just abandoning ourselves to the influence of nature upon the spirit. Something better may come out of that than the discovery of a new plant or the identification of a long-sought bird.

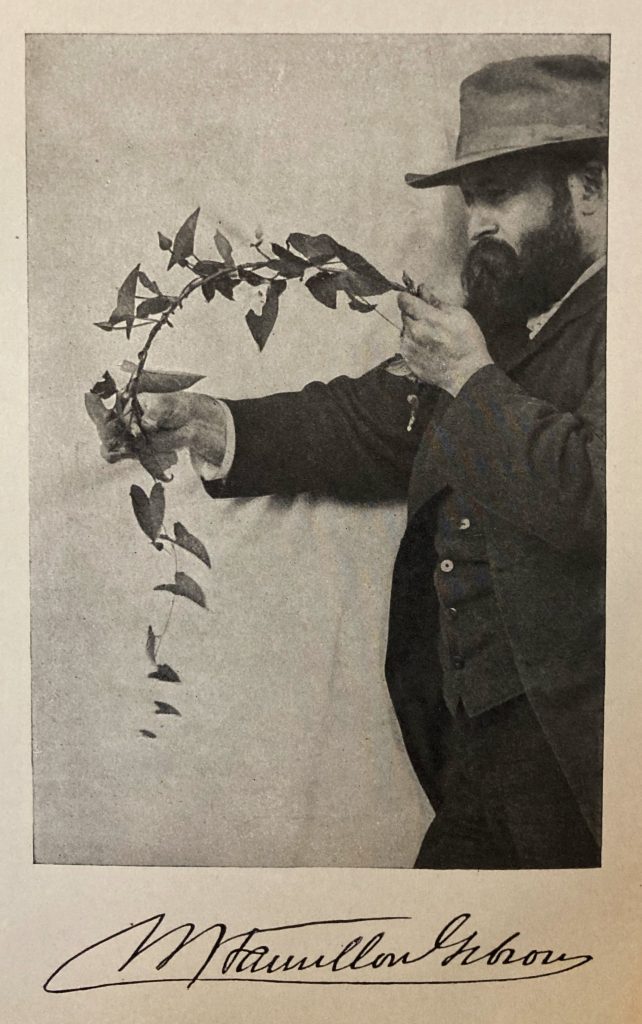

There is nothing spectacular about the works of James Buckham, or his life, for that matter. As far as I have been able to find out online, there is precious little biographical information about him (no Wikipedia entry!) and no photograph or other image of him. The closest I could find was a picture of his gravestone. He was born on November 25th, 1858 in Burlington, Vermont, and died only 49 years later, on January 8th, 1908, in Melrose, Massachusetts. In-between the two, he was well educated, obtaining a BA and MA. Evidently he planned a future in the theological seminary, but voice-related problems sent him into journalism instead. In 1895, he married Mary Bingham of Hyde Park, Vermont. After 18 years of journalism, he left the field to become an essayist, poet, fiction writer, and nature writer. As far as I have been able to tell, he published only two works about nature in his lifetime: “Where Town and Country Meet” and “Afield with the Seasons” (review coming soon). His cause of death is unknown.

Buckham’s book “Where Town and Country Meet” is a pleasant volume but nondescript compared to many of its time. The cover features only the title at the top and the author name at the bottom, gold-embossed on gray-green cloth. There are no illustrations of any kind, unless one counts the decorative insignia on the title page above. And there is little that is striking about the volume. It is a pleasant read, certainly. Like many other nature writers of his time (and not surprisingly, considering his theological bent), Buckham views nature experiences as opportunities for appreciating the wonders of God’s creation. This outlook leads him to extol “the impressions of nature as a whole”, in the passage above and in this one, from a page earlier:

One is not much disposed to observe minutely, I think, on a September tramp. The last of the birds and the last of the flowers may challenge a somewhat languid interest, but for my own part I like to take things in the mass, in the aggregate, when nature’s long season of emphasized indivi ualism is on the wane. For months we nature-lovers have been burdening our brains and note-books with observations of concrete life in a thousand different forms. Innumerable birds, flowers, insects, trees, plants, and four-footed creatures have confronted us at every step and stimulated curiosity and study. Now the birds have mostly departed, the flowers are a few and sedate company, the insects are frost-killed or driven into retirement, and I for one am tired of particularizing, and am glad to go back for a time to those free, buoyant, youthful impressions of nature as a whole. Instead of pulling to pieces single flowers I want to let my eye range over a whole living field of them, assembled in a carpet of purple and gold. I do not care to ask their names. I simply want them to make an impression of beauty and harmony and joy upon my spirit.

To speak of this as any sort of proto-ecological thinking would clearly be excessive. Yet, given the many writers of his time (Bradford Torrey being a fine example), nature experiences mostly involved identifying and watching birds, flowers, or the two in alternation. To pause and appreciate nature taken altogether I found refreshing.

That said, Buckham could also appreciate the particulars of an Eastern woodland. Here is his joyous tale of wandering the land in early springtime:

I had scarcely entered the woods when in the crumbling, disintegrating snow I found the wiry, nervous, wandering tracks of a ruffed grouse, which had evidently been abroad that very morning, far earlier than I, to seek a breakfast of leaves and berries on the knolls uncovered by the heat of the sun. I followed the winding trail for some distance, but finally it so turned, and doubled, and intertwined with itself, that I lost my clue and had to give it up.

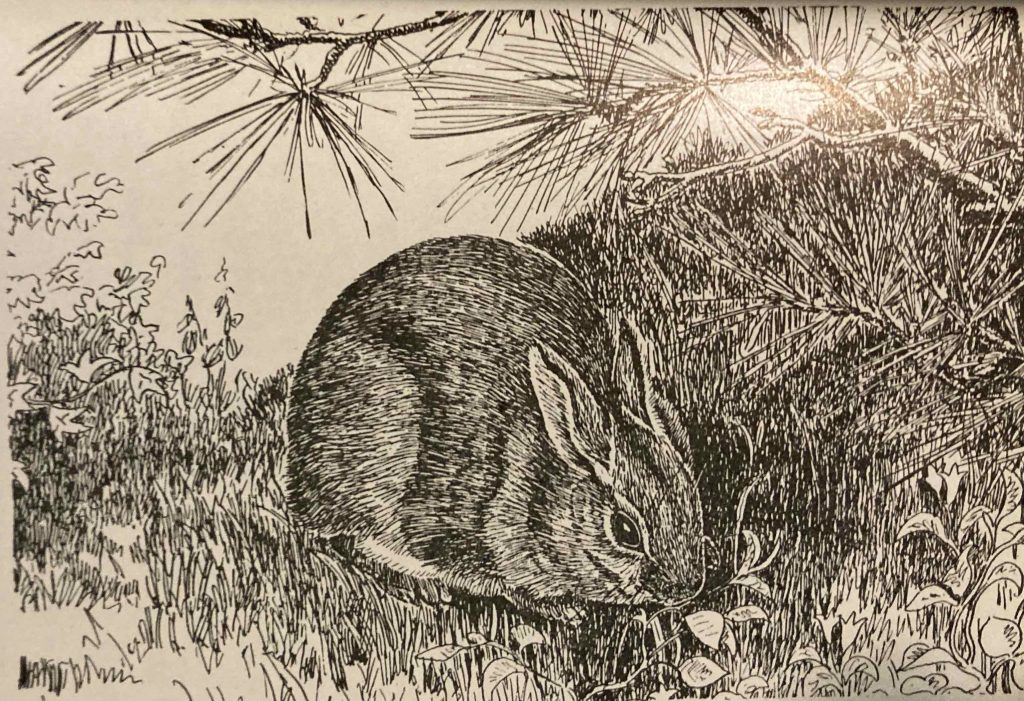

Everywhere, from the trustworthy record of the snow, it appeared that the squirrels had been on the move likewise, passing from tree to tree with long, joyous leaps, the vigor of spring already in their veins. Many rabbit tracks through the thickets showed where the cottontails also had chased each other, like those black lovers in midair. All this awakening and new activity seemed a part of the glad expectation of spring.

The skunk-cabbage was thrusting its spearpoint up through the black loam along the brook earliest of all the wild sod breakers. I found the alder-buds swelling beneath their scales, and the catkins of both alders and willows already visible. There was bright green cress in the bed of the brook, and a few spears of green grass lifted themselves out of the loam in a shel tered, sunny corner of the swamp. Chickadees were lisping their faint dee-dee-dee in the hemlocks; jays were screaming lustily among the dwarf oaks ; and a yellow-hammer sent forth his clarion challenge from the hillside. Everywhere the decomposing snow was black with myriads of tiny, sput tering snow-lice, that darted hither and thither like sparks out of a fire. Surely, spring was in the air and underfoot! It was good to be abroad at the first whisper of her coming.

Buckham’s joy here is palapable and contagious. Reading his gleeful observations, I am sorely tempted to put down the book and step outside — into the steamy heat occf a climate-collapse summer heatwave in Georgia. The more I read these works from a hundred years ago or more, the greater my sorrow that the relative constancy of weather — and the relative abundance of many animal species — are both rapidly becoming things of the past.

Although the book focuses primarily on nature’s beauty as an experience of God, I do not want to leave readers thinking that he entirely lacked a scientific perspective or grounding in natural history. Inspired by Thoreau, he dined on thawed, wild apples, pronouncing them delicious indeed:

Beyond the golf links, on a hillside where scattered birches and scrub pines were growing, I came upon a stunted wild apple tree, the ground under which was thickly strewn with frozen and thawed apples. Immediately there occurred to me Thoreau’s enthusiastic praise of the spicy cider of thawed wild apples. Gathering my hands full of the russet fruit, I sat down upon a rock to taste this primitive nectar (as Thoreau recommends) “in the wind.” It was indeed delicious–not so tart and bitter as the juice of the wild apple in its sound state, but distinctly sweetened and ameliorated by the frost; a kind of spicy wild wine, innocent as water, refreshing to the palate, and wholesome and medicinal to the entire body. I gathered more and more of the wild apples, and sucked their cool nectar until my thirst was slaked. It was a real discovery, this new winter drink, and I would heartily pass on Thoreau’s recommendation of it to other ramblers.

In other passages, Buckham remarks on evolution by natural selection as a guiding biological principle. And most intriguingly, he writes about the urban heat island effect — I had never guessed this phenomenon was already recognized back in 1903! He notes how cities in summer reflect “abnormal conditions through which man artificially intensifies a phenomenon of nature. A hot wave raises the temperature of New York City from five to ten degrees above that of the surrounding country; but it is an adventitious supremacy, due to intercepted air, heated bricks, and blistering pavement.” (I have to admit that Buckham lost me there on the “adventitious” part.)

Still, these passages are exceptions to the general rule. This is a book whose audience was clearly those of a somewhat religious bent, laboring in urban workspaces (mostly executive offices, I would guess) but craving a taste of nature just beyond the city limits. Buckham does well at evoking such experiences in text. The result is a truly pleasant read, if a bit bland at times. Still, it is good to celebrate the poetic in nature, and that is how I will close out this post:

I am thoroughly in sympathy with those who think that too much exact knowledge takes something of the romance and poetry out of our acquaintance with nature. There must be a certain indefiniteness, a certain hazy quality, in our knowledge of the outer world we must not, in a word, know nature too well or we shall miss that elusive charm which pervades the poetry of Wordsworth, for instance. I am not sure but that we should be more appreciative nature lovers if we did not feel obliged to identify and mentally catalogue every creature and plant we see and every song or cry we hear.