The April showers touch with caressing fingers the chords of all things and bring music from them, each according to its kind. In the open forest under deciduous trees the dead leaves thrummed a ghostly dirge like that of the “Dead March in Saul.” Winter ghosts marched to it in solemn procession out of the woodland. Memories of sleet and deep snow, ice storm, and heartbreaking frost, tramped soggily in sullen procession over the misty ridge and on northward toward the barren lands to the north of Hudson’s Bay. Thrilling through this solemn march below I heard the laughing fantasia of young drops upon bourgeoning twigs above, dirge and ditty softening in distance to a mystic music, a rune of the ancient earth.

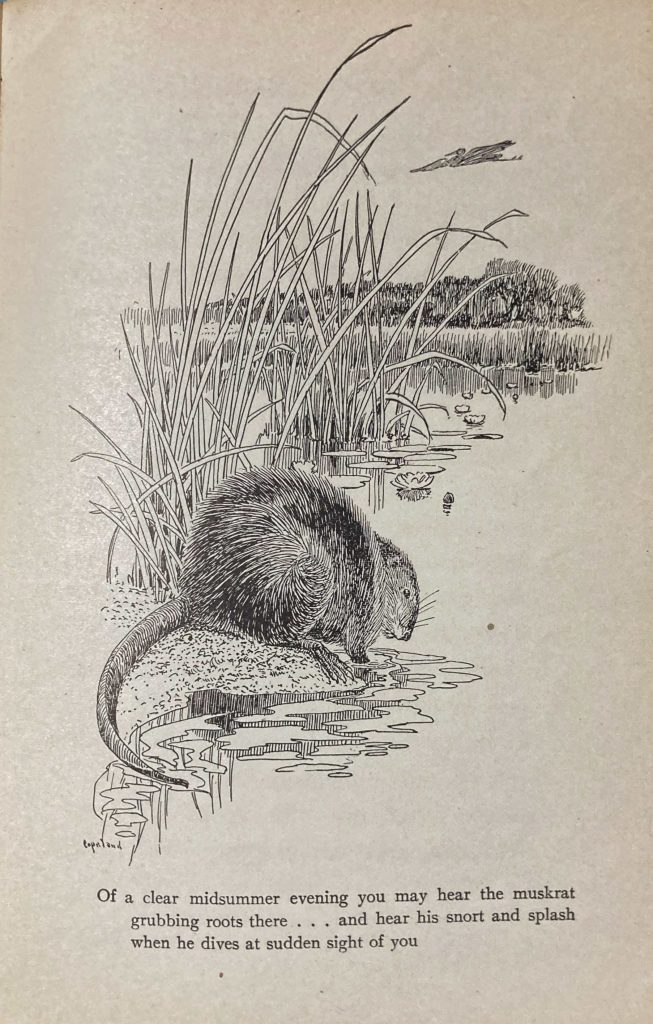

In the open pasture the tune changed again. It was there a chirpy crepitation that presaged all the tiny, cheerful insects whose songs will make May nights merry. These, no doubt, take their first music lessons from the patter of belated April showers on the grass roofs of their homes. But it was down on the pond margin that I found the most perfect music. Slender mists danced to it, fluttering softly up from the margin, swaying together in ecstasy, and floating away into a gray dreamland of delight. It was the same tune, with quaint, syncopated variations, that the budding twigs and the brown pasture grasses had given forth, but more sprightly and with a bell-like tinkle more clear and fresh than any other sound that can be made, this tintinnabulation of falling globules ringing against their kindred water.

Every drop danced into the air again on striking and in the mellow glow of an obscure twilight I could see the surface stippled with pearly light. Then through it all came a new song; the first soloist of the night, the first of his kind of the season, thrilling a long, dreamy, heart-stirring cadenza of happiness, the love call of the swamp tree frog.

With this passage, Packard traces the liminal world of winter becoming spring, as experienced at Ponkapoag Bog in Blue Hills State Reservation on the southern edge of Boston. What I find entrancing in this passage, and much of his work is his ability to blend fairly accurate natural history with an air of mystery, of faerie even. There is an old magic that haunts the edges of Packard’s woodland wanderings. Yes, there are frogs calling — but maybe, too, they are wood sprites humming an ancient melody. In that magical landscape, Packard shares about how he “could feel the happiness of the pasture shrubs.” Raindrops do not merely fall from clouds — they dance and sparkle and tap upon the leaves. This is a much more animate (and animated) vision of nature than many more scientifically inclined nature writers might suggest. He evokes wonder by entertaining just enough doubt about his experiences that he leaves a space for ancient magic to dwell and take root. For example, he writes about his time silently watching the goings-on in a bog that “As I sat quiet, hour after hour, in this miniature wilderness, I came to hear many a strange and unclassified sound that, for all I know, may have been fay or frog, banshee or bird.” Like an impressionist painter, Packard engages with the wetland not only with the objective gaze of scientist, but also with the soul of a poet and mythologist. The result is a world in which frog and fae commingle as one. It is a world, too, of the imaginative experiences of my own childhood. I recall walking through the woods behind my house and imagining all sorts of other worlds, from a path through Mirkwood in Middle Earth to a swamp at the time of the dinosaurs. Where a sapling was bent over by an ice storm, there would be a portal into another place, another landscape of my own creation, fecund with possibility.

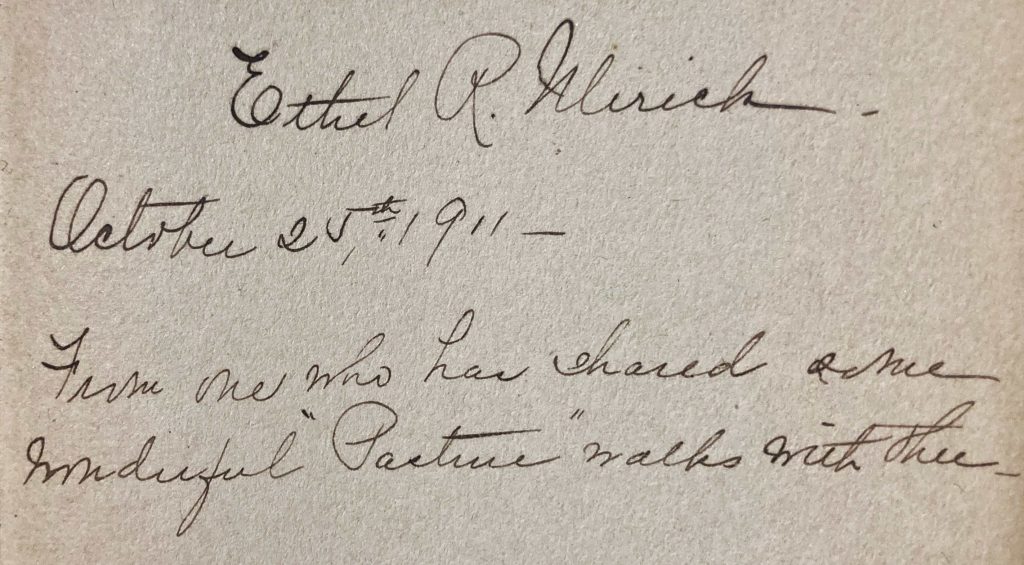

This volume is one of four chronicling the seasons in Packard’s corner of Massachusetts. Taken together, their titles are “Woodland Paths” (spring); “Wild Pastures” (summer); “Wood Wanderings” (autumn); and “Wildwood Ways” (winter). This is the third volume I have obtained and chronicled in this blog. “Wood Wanderings has remained unobtainable in its original form; I have settled for a Kindle edition that I will read someday. I do have to say that Packard managed to choose four titles that are practically impossible to keep straight. And on Thriftbooks, where reprints of “Wood Wanderings” are sometimes sold, “0 people are interested in this title.”

Few people, too, appear interested in Winthrop Packard himself. He has no Wikipedia entry. The “Lit2Go” website provides his birth and death dates (1862 and 1943, respectively) and tersely sums him up in two sentences. The first claims that “Winthrop Packard is best known for his novels of the nature genre.” This is patently untrue; his books contain nature essays; they are most definitely not novels. The second sentence merely lists several titles he wrote. Fortunately, Praweb.com offers a slightly more extensive overview of his life. You can read more about Packard in my earlier blog post on his “Wild Pastures”.