These Spring days, when we hear the bluebirds carol, and mark the revivifying influence of the season, we are sure to be affected thereby, and my companion smiles to see me dance beneath the pine tree. ” You seem happy,” he says, and yet I notice the light kindle in his own eyes, for the sunshine, the bluebirds and the robins have not come in vain to him.

What a blessing are the balmy hours of Spring! The warm sun distills a fragrance from the earth, and in the waste pastures, where there is a thick mat of vegetation, this odor is particularly strong. Nature is stirring straw- berries and crickets into life. The air is full of little flies, beetles run along the roadway, dogs lie asleep on the grass and the yellow flicker sounds his rattle in the trees. Then does the light within burn brightest, and our hearts seem to beat more joyously than they have all Winter long, and we are happy and at least transiently well under the sun. Old Sol smiles at our ways; we are flies on the sunny side of a pumpkin to him, and to ourselves we know not what we are.

It is a blessing to retain the simple delights of childhood, to be easily pleased, and it is well to be affected by the greening of the earth, even though we cannot exactly mention the charm or tell why we should be glad. It is no wonder that there have been May-poles, no wonder that the shepherds of old danced about the straws in the field at the feasts of Pales, and no wonder again that my companion and I become joyous in the hopeful days of Spring.

A child-like wonder infuses William T. Davis’ work, Days Afield on Staten Island (1892). With curiosity, wonder, and delight he explores the scruffy landscapes of a long-inhabited place, from its vacant lots and old orchards to its tidal marshes and its tumbledown farmhouses. He ventures afield through the seasons, describing both the remains of past inhabitation and the plants and animals that have taken over now that the human occupants are gone. In a time when much of Staten Island was still somewhat rural, he provided a series of charming vignettes of places that are now largely (though not completely) gone. I suspect he saw what was coming, though. In his second essay, “South Beach”, he observed that “not only do the land animals fall year by year before advancing civilization, but the life that ocean would seem to hold so securely, is also being gradually stolen away.”

Throughout his book, there is a haunting presence of the past. At one point, he explores an abandoned farmhouse, finding old ledgers and other artifacts strewn about the home. The dead are never far away; they linger at the edges of our sight. In the passage below, the Revolutionary War is remembered in the landscape.

In April the blood-root blossoms, and its single leat often closely clasps the flower stem, forming a sort of green collar. It is a dainty flower but none too choice to deck the steep hill sides of the crooked and shaded ravine where it grows in greatest profusion. This is Blood-root Valley and Blood-root Valley Brook, along the course of which, it is said, a British messenger, in Revolutionary days, travelled on his way from camp to camp. This stream, which is often dry in summer, also rises near the highest point, and goes to form the Richmond brook. The drainage of the district was formerly collected in a pond, used by a saw-mill, of which there is now only a few beams left, and the dam is broken. About 1870, the boys bathed in this pond, and a little lame boy with crutches and a board for support, used to enjoy himself as much as his companions.

A number of skirmishes occurred along Richmond or Stony brook, in the years of the Revolution, particularly on the day of the fight at St. Andrew’s Church. But it is more pleasing to think of it in the times of peace, to see the water snakes glide in so smoothly, the turtles scuttle with much haste and the wayward frogs jump recklessly off the bank frightening the black-nosed dace below. When these little fish are disturbed, they will scatter in all directions, coming together shortly, if they imagine the danger is past. At other times they will sink to the deepest places in the stream, and remain on the sand or pebbles, not moving a fin, and as their backs are sand colored, they are not easily seen from above. Occasionally when there is nothing to fear, one will be seen lying motionless for a long time between two pebbles, and thus can they rest and sleep when they desire.

And here, in this passage, the Indian presence is evoked by scattered potsherds:

To the east of the Bohman mansion, near Bohman’s Point, there is a little brook, that flows through a sandy semi pasture and woodland region. It is bordered in part by willows and old orchard trees, and the land has that unmistakable air of an ancient farming spot. On the high sand dune, nearby, about which this brook bends in bow fashion, the Indians lived in old time, and their implements and little heaps of flint chips, where the arrows were made, may still be discovered. The spring, where they got water, is on the hill-side, though now filled up with sand and grass grown, but the stones that formed its sides mark the site, and a tiny rill issues from among them in very wet weather.

They had an eye for beauty, as evinced by the patterns on the broken pieces of pottery lying about, and no doubt they thought the warblers very gay, that congregate in spring-time about a moist place near the brook. The warblers come every year, just the same, but the Indians are gone, and probably in the large factory across the Kill with its thousands of employes, only one or two would recognize their implements scattered among the other stones on the sand.

Finally, here is one last passage from the book, a charming vignette from the autumn time:

It is good to ramble in the autumn fields, in one of the barren sandy nooks where the sweet-fern grows, and where a sad pleasant flavored joy, seems to pervade all about you. With dextrous throws you bring down the apples, and though they may be gnarled and puny, you eat them with a relish, for they seem such free gifts from nature. They come without the asking or the toil, like the persimmons, or the strawberries in the field.

Autumn colors the barren ground vegetation very early with the deepest dye, and as we are taller than most of the plants that grow on the sand, we may look over them, and thus get a wide and varied view. The Virginia creeper runs flaming red along the ground, and the sumachs, the cat-briers and the poison ivy vines, are most vividly colored.

Perhaps the most curious tint of all the autumnal show is the greenish-white leaves of the bittersweet vine, that are speckled with yellow. They have an odd appearance, for all about them the leaves have turned to most vivid colors, while they alone have assumed so white and ghostly a shade. In the chestnuts and some of the oaks, the green color remains longest near the mid-rib, and in the oaks it is often a deep olive shade, and greatly adds to the beauty of the turning leaf. The wild cherry trees color an orange red, and the seedling cultivated cherries are flushed with red and look to be in a fever. The chestnut-oaks turn a light yellow, as do the chestnut trees and the hickories.

There is a vividness of color in many of the leaves that seems almost supernatural, and it is plain that we, who live and grow old on the Earth, can never cease to wonder at the yearly display. ” Look,” says the little boy, “at that Virginia creeper,” and in manhood he points again in wonderment at the flaming red vine in the cedar tree.

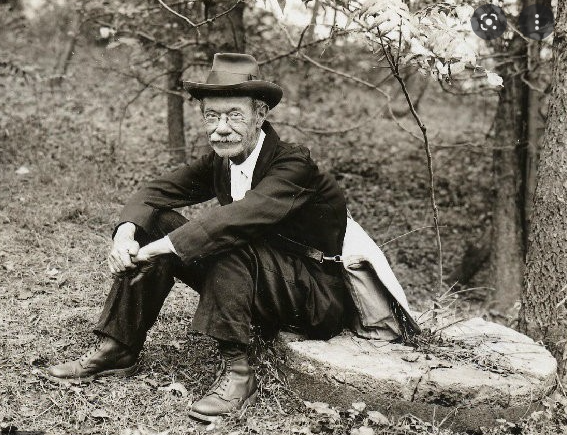

A few words about this book and its author are in order. I confess that I broke down and purchased a modern-day paperback copy; the originals are far outside f my price range, even though the book contains no illustrations whatsoever. At the time, I had assumed the author is unknown. In fact, William Thompson Davis (1862-1945) has a National Wildlife Refuge on Staten Island named after him. The property is now only 30 acres smaller than Central Park. Working with the Audobon Society, Davis helped secure the original 52-acre parcel back in 1928. Davis himself was a naturalist, entomologist, and historian. This was his only nature volume for a general audience, although he also published some scientific work on cicadas (ironically, cicadas are not mentioned in this book). Much later in his life, in 1930, he co-authored a five-volume history of Staten Island.