We waited for the spring with an eager longing; the advent of the growing grass, the birds and flowers and insect life, the soft skies and softer winds, the everlasting beauty of the thousand tender tints that brought us unspeakable bliss. To the heart of Nature one must needs be drawn in such a life….

AFTER READING A NUMBER OF AUTHORS WHO SCRUTINIZED NATURE THROUGH A SCIENTIFIC LENS, CELIA THAXTER’S MEMORIES OF LIFE ON THE ISLES OF SHOALS WAS A REFRESHING SEA CHANGE. “Among the Isles of Shoals” is not, strictly speaking, a work of natural history; rather, nature imbues its pages because it is impossible to avoid elemental forces from atop small bits of rock with veneers of soil, perched on the edge of a vast ocean, nine miles’ journey from the New Hampshire mainland. Encountering nature is an inevitable part of living there. Thaxter’s writing rambles, like a tourist to Appledore Island might do. There are no chapters; the reader is pulled into the author’s island world and swept along from one topic to the next, running the gamut of past settlers, folkways, weather patterns, past storms, shipwrecks, the seasons, the sky, the birds…. I like to think that the blending of topics in this manner is somewhat intentional, an organic form emerging out of the experience of inhabiting a small island:

The eternal sound of the sea on every side has a tendency to wear away the edge of human thought and perception; sharp outlines become blurred and softened like a sketch in charcoal; nothing appeals to the mind with the same distinctness as on the mainland, among the rush and stir of people and things, and the excitements of social life.

It is a landscape where nature predominates; remnants of the human past become worn down and lichen encrusted, and eventually lost.

When man has vanished, Nature strives to restore her original order of things, and she smooths away gradually all traces of his work with the broad hands of her changing seasons.

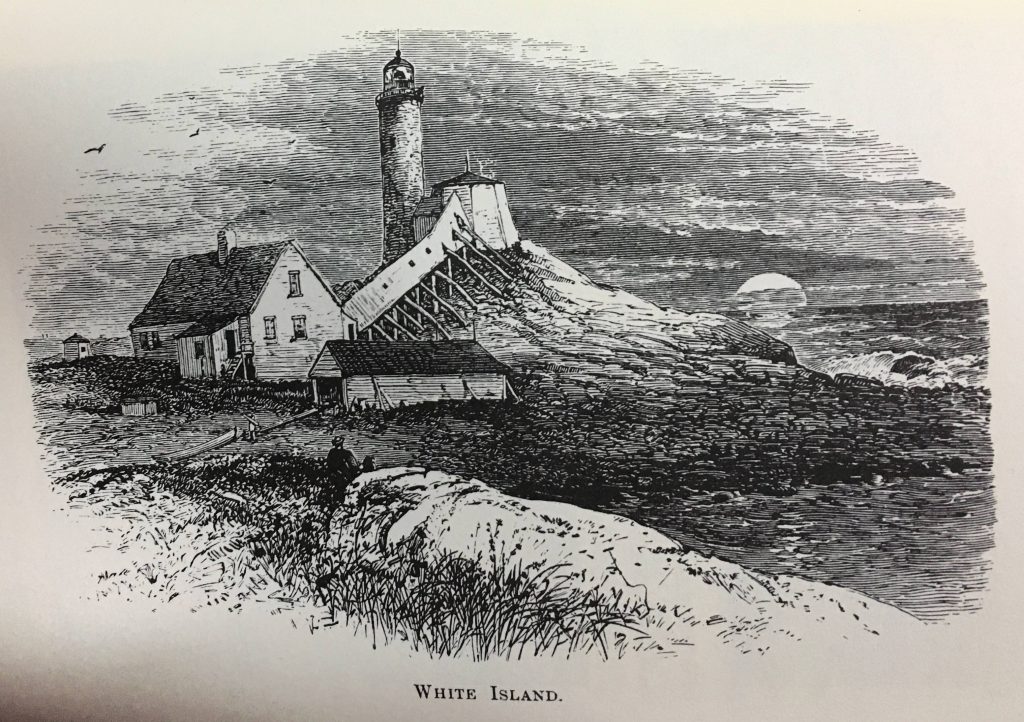

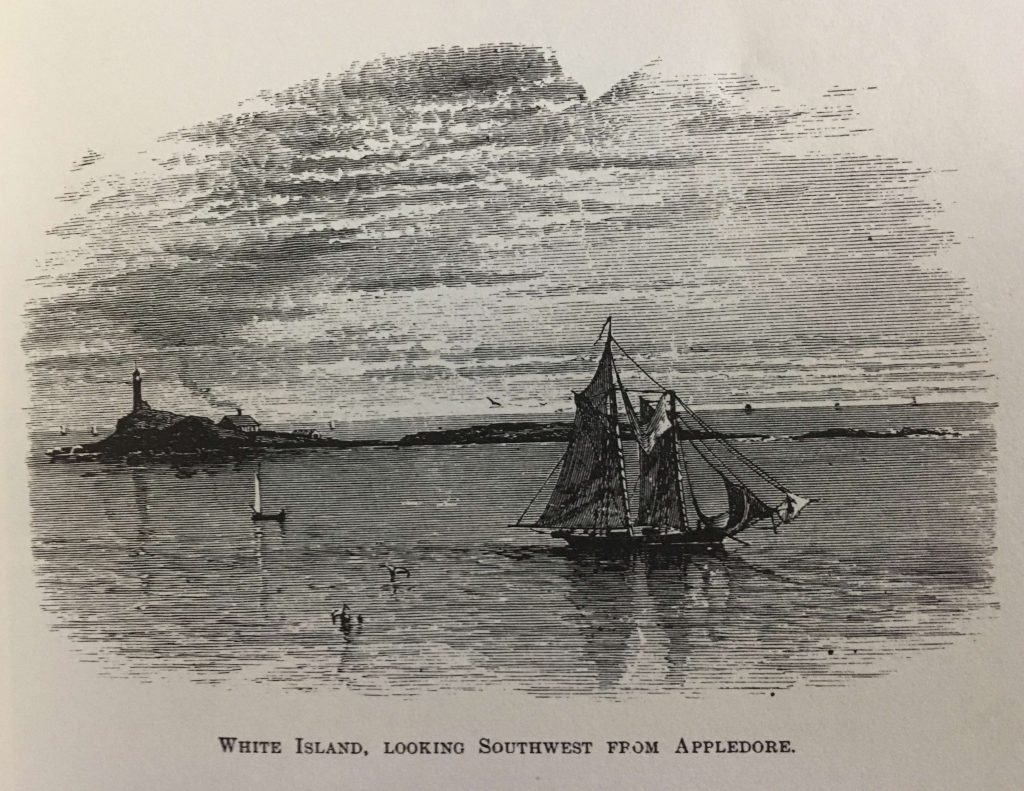

THE MOST DELIGHTFUL PAGES IN THIS BOOK SPEAK OF THAXTER’S EARLY CHILDHOOD, SPENT AT THE LIGHTHOUSE ON WHITE ISLAND. She was “scarcely five years old” when her father became lighthouse keeper there. Celia and her two brothers grew up among the rocks, waves, birds, and flowers of a tiny, treeless island. Bereft of a social world beyond her own family, Nature instead provided her with everything she needed — companionship, play, and wonder. Over a span of about twenty pages, Thaxter magically evokes those experiences for the reader. Consider this extended passage, in which she speaks of the childhood mysteries and delights of White Island’s flowers:

I remember in the spring kneeling on the ground to seek the first blades of grass that pricked through the soil, and bringing them into the house to study and wonder over. Better than a shop full of toys they were to me! Whence came their color? How did they draw their sweet, refreshing tint from the brown earth, or the limpid air, or the white light? Chemistry was not on hand to answer me, and all her wisdom would not have dispelled the wonder. Later the little scarlet pimpernel charmed me. It seemed more than a flower; it was like a human thing. I knew it by its homely name of poor-man’s weatherglass. It was so much wiser than I, for, when the sky was yet without a cloud, softly it clasped its small red petals together, folding its golden heart in safety from the shower that was sure to come! How could it know so much? Here is a question science cannot answer. The pimpernel grows everywhere about the islands, in every cleft and cranny where a suspicion of sustenance for its slender root can lodge; and it is one of the most exquisite of flowers, so rich in color, so quaint and dainty in its method of growth. I never knew its silent warning fail. I wondered much how every flower knew what to do and to be; why the morning glory didn’t forget sometimes, and bear a cluster of elder-bloom, or the elder hang out pennons of gold and purple like the iris, or the golden-rod suddenly blaze out a scarlet plume, the color of the pimpernel, was a mystery to my childish thought. And why did the sweet wild primrose wait till after sunset to unclose its pale yellow buds; why did it unlock its treasure of rich perfume to the night alone? Few flowers bloomed for me upon the lonesome rock; but I made the most of all I had, and neither knew of nor desired more. Ah, how beautiful they were!

FOR THAXTER, LIFE ON THE ISLES OF SHOALS WAS A STREAM OF ENCOUNTERS WITH EVER-CHANGING ELEMENTAL PRESENCES. Everywhere she looked, she found entrancing forms and colors, shapes and scents, waves and winds. I will close the post with this enchanting collage of island experiences:

Nothing is too slight to be precious: the flashing of an oar-blade in the morning light; the twinkling of a gull’s wings afar off, like a star in the yellow sunshine of the drowsy summer afternoon; water-spout waltzing away before the wild wind that cleaves the sea from the advancing thunder-cloud; the distant showers that march about the horizon, trailing their dusky fringes of falling rain over sea and land; every phase of the great thunder-storms that make glorious the weeks of July and August, from the first floating film of cloud that rises in the sky till the scattered fragments of the storm stream eastward to form a background for the rainbow, — all these things are of the utmost importance to dwellers at the Isles of Shoals.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT MY COPY OF THIS BOOK. It is a paperback, from 1994, belonging to my wife; the book is a reproduction of the original 1873 edition. My wife studied marine biology on the Appledore Island in the Isles of Shoals, and likely purchased this book a few years later. It includes a few photos of the island from the time, including one of some buildings on Smuttynose Island, among which is the “Honvet House…where famous murders were committed in March 1873.” For those keen on learning more about 19th century New England axe murders, here is an article on what happened there. If you choose to check it out, remember, you axed for it.