The book is quite literally falling apart. The pages are browned and foxed, the cover fabric (sporting a gilt impression of a moth) is pulling loose from the spine, the binding disintegrating. It feels like an old book. And it is. B. (Benedict) Jaeger’s volume on North American Insects predates the Civil War. It is the oldest book I have read for this blog so far, taking us back toward the beginnings of the late 19th Century’s fascination with nature. My volume is copyright 1859, though the book was published five years earlier, in a more limited edition that included five color plates (and costs considerably more today than this one). And 1859 was — as diehard natural historians likely know — the year that Charles Darwin published his “Origin of Species”. Jaeger’s writing offers a window into the foreign and intriguing world of natural history before evolution revolutionized it. Terms and concepts that evoke a kind of proto-ecology jostle on the page with paeans to God’s handiwork, in a book that at times is as much a religious text as a biological one. And through it all, the rambling voice of Benedict Jaeger, world traveler, natural philosopher, and bane of editors.

Who was Jaeger? The title page of the book notes that he was a “late Professor of Zoology and Botany for the College of New Jersey.” According to Bugguide.net, a catalog of his papers at Princeton University notes that he was a professor of natural history and modern languages at Princeton from 1832 until 1843. He was born in Vienna, Austria in 1789, and died in Brooklyn, New York in 1869. He supposedly wrote many books on insects. And that is all I was able to find out about him, besides what might be gleaned from his travel stories scattered throughout this book.

Given the year the book was published, and the fact that Henry David Thoreau lived until 1861, could he have read this book, or at least glanced at it? For all that it is unknown today, Jaeger’s rather slender tome was the first general book on North American insects ever published. Though far from a field guide as we know it today (relatively few insects are covered at the species level, and amounts of information on different types of insects vary widely), the book was still a landmark in American entomology. So I like to imagine Thoreau thumbing through it (and possibly frowning at some of its more extreme anthropocentric declarations). And, in fact, he probably did. The Concord Library website includes a listing of books from the library of Edwin Way Teale (scholar of Thoreau and a nature writer to boot). The list includes the following item:

Jaeger, Benedict. The Life of North American Insects. By B. Jaeger … Assisted by H.C. Preston, M.D. With Numerous Illustrations from Specimens in the Cabinet of the Author. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1859.

319 pages. Illustrated. 19.5 cm.

Inscription in ink on front free endpaper: A duplicate of one / of the insect books / that Thoreau used. / For the Teales from / the Walter Hardings. / Hampton, Conn., August / 20th, 1963.

A few marginal markings in pencil.

How exciting! That said, I am quite confident that Jaeger’s outlook on nature was not one that Thoreau shared. And as a tool for insect identification, it was definitely wanting.

“Philosophy,” Jaeger declares in his opening line, “has invested even the commonest objects of Nature with charms unknown to the uneducated.” But why study insects, in particular? Ultimately, because insects are useful:

It is time that our people in general, and particularly our youth, should be made acquainted with a class of animals which everywhere surround us, day and night, and which furnish us amusements, food, coloring substances, and medicines, in order that they may be able to distinguish the useful from the injurous ones, the harmless from the noxious, and to discover those which may furnish new articles for manufacture, commerce, and domestic industry.

There is a deeper reason, though (cue choir of heavenly angels). Learning about insects opens the door to “…a more general knowledge of Natural History, and a deeper admiration of the ten thousand sublime and beautiful creatures that, in one common song of praise, pour out their gratitude and proclaim their dependence upon one common Father.” In this image, Jaeger evokes spiritual unity — there is a whole to nature because nature is holy. And that implies that the individual constituents of the natural world (living and nonliving) must interact and function as one great system. Here, he was inspired in part by Alexander Humboldt, whose first volume of Cosmos was published in 1845:

…we find all these different varieties of the three natural kingdoms [plant, animal, mineral] united under one general law; all dependent upon one another, as component parts of one great universal whole, aand we are forced, with he great philosopher Humboldt, to exclaim, “Nature is the unity in variety.”

Intriguingly, going down this path leads Jaeger to affirm principles that would years later be echoed in rudimentary ecology. Since nature is a system created by God, there cannot be any part that is irrelevant or without purpose: “…none of the works of nature are so insignificant as to be wholly without use in the great plan of economy.” How does that plan work? Consider the caterpillars, Jaeger suggests, who feed on plants and therefore pose a threat to agriculture. The obvious choice would be to kill them all, to safeguard our crops and flowers. But that would be unwise, Jaeger cautions:

…were we to annihilate caterpillars, our gardens, wods, and fields would be abandoned by the whole feathered tribe who feed on them, and melancholy sadness shroud the abodes of man. Ardently, then, would bwe long for the return of the oxious Caterpillars, and with them the joyous songsters of the forest. …so beautifully is the doctrine of compensation illustrated throughout the Animal Kingdom, as well as in all the objects of Nature.

Elsewhere, Jaeger refers to this same principle as the law of antagonization instead:

[Insects] afford a constant evidence of the working of Nature’s great law of antagonization — the one undoing wha the other does; the injuries which one species would infliec upon man are checked by other species, which prevent their superabundance and keep an even balance in the scale of being.

Carrying capacity, anyone? Ironically, this law does not prevent Jaeger from declaring firmly a few pages later that herbivorous beetles “are noxious and should be destroyed wherever encountered.” There appears to be a disconnect between Jaeger’s pre-ecological mindset and practical reality.

Lest we extoll this pre-Darwinian model of the Cosmos as brilliant and ahead of its time, while Nature may be a system created by God, it is still a hierarchical one. And guess who is at the top?

It is more than wonderful, it is sublime, to view atom after atom of the whole creation unceasingly changing place, that man, the lord of creation, may be abundantly supplied with all his comforts and his luxuries.; to see the lilies of the field, and the insects of the earth and air, living and dying for man, yielding up their lives for man’s sustenance and adornment.

To rework a line from George Orwell’s Animal Farm, “All living things are significant, but some are more significant than others.” “The great plan of economy,” is clearly under man’s rule. At least one can find a bit of solace, though, in the fact that women are not entirely forgotten: “I write also for the young ladies,” Jaeger announces midway through his book.

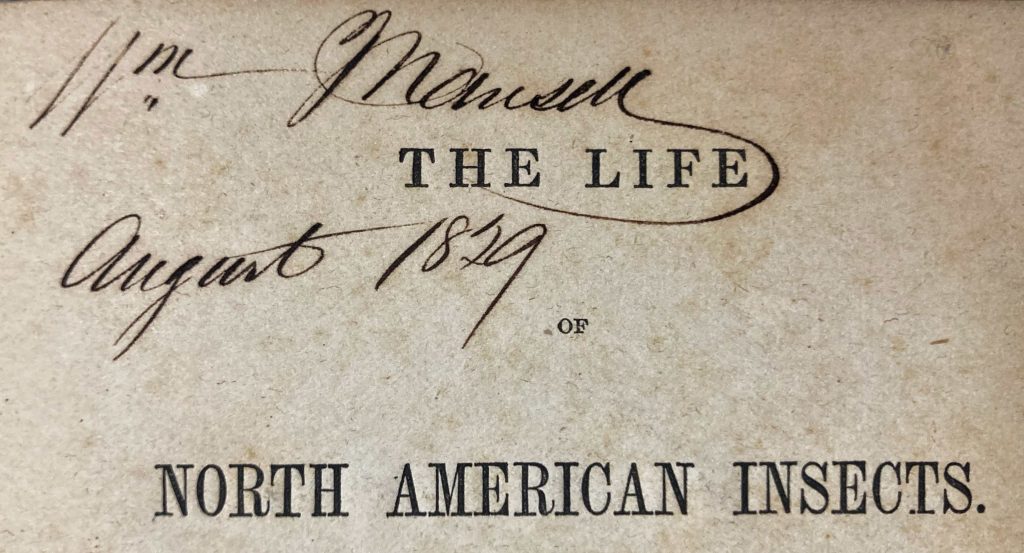

My copy is definitely in “fair” shape. For its considerable age, all I can say about the book’s past is that it was once owned by William Mansell (thank you, Kent, for your correction on my reading of this signature), who dated it August 18?9. (My guess is that the mysterious digit is a 5, as it could not be a 2. Given that the book was published in 1859, it is most likely that Maxwell obtained it then.) Efforts to find information about William Mansell online were unsuccessful. There are plenty of somewhat famous persons with this name, but none of them quite fit this time period.