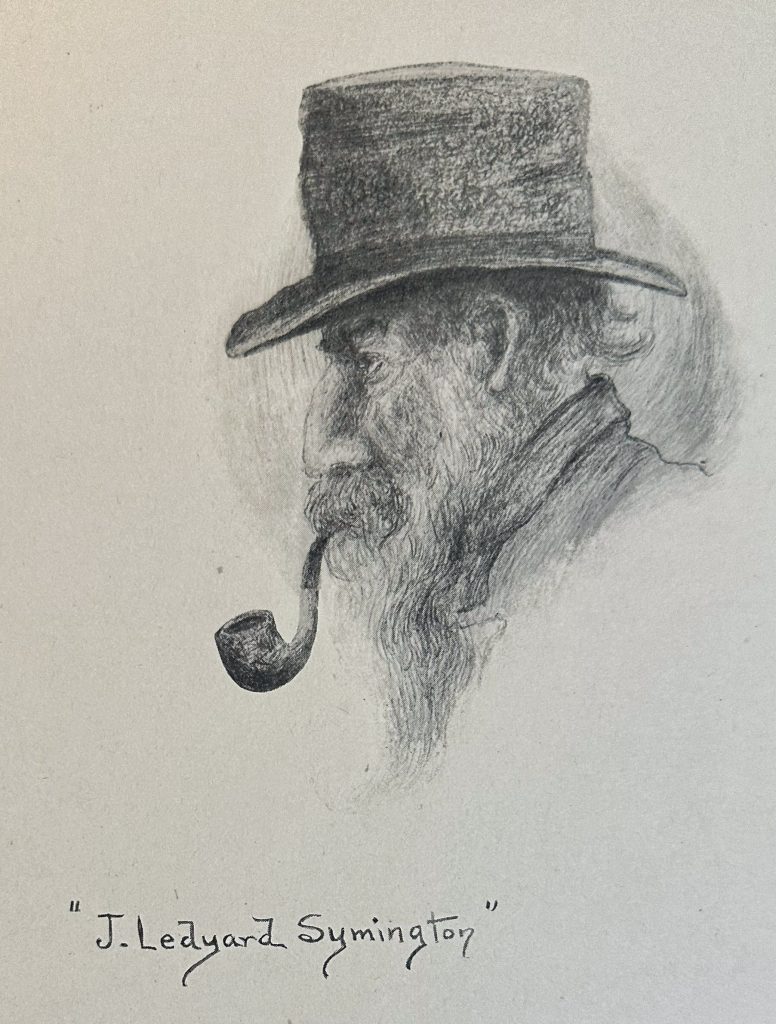

In this blog post, I am playing a bit of a catch-up, writing about six different books I have read recently by five forgotten nature writers, all of whom have previously appeared in this blog, and at least three of whom will likely return in the future. C.C. Abbott (1843-1919; left, above) was an amateur naturalist and archaeologist, who lived outside Trenton, New Jersey, and wrote mostly about the natural history of his marshland property and adjacent lands. Though quoted by many at the time (and participant in a heated debate about early human presence in America, which he argued pre-dated the last Ice Age), is known today only as the figure for whom Abbott Marshlands Park was named. James Buckham (1858-1908; no photo found), was a journalist and writer who lived in Melrose, Massachusetts. He does not currently have so much as a Wikipedia entry. Walter Prichard Eaton (1878-1957; right, above) was a theater critic and writer; for at least the last ten years of his life, he wintered in North Carolina and summered at his home in the Berkshires. He has a brief Wikipedia entry and a slightly longer New York Times obituary (courtesy the Way Back Machine). Ernest Ingersoll (1852-1946; not pictured above) was a naturalist and explorer of the West (including the Hayden Geological Survey of Colorado in 1873) and an early advocate for conservation. Born in Monroe, Michigan, Ingersoll spent most of his life in New York City. Finally, Bradford Torrey (1843-1912; middle, above) was a nature writer and ornithologist, whose books of nature rambles with birding and botanizing were quite popular during his lifetime. Torrey is essentially forgotten today; even the Torreya Pine (whose wild habitat is limited to a small park in the Florida panhandle) was named for a distant relative, not for him. Born in Weymouth, Massachusetts, he spent most of his life in Boston before moving out to Santa Barbara, California where he spent his final years.

What all of these books have in common is that they were enjoyable but, for the most part, not particularly noteworthy. I have yet to read many writers from my chosen time period whose prose is abjectly painful to ingest (apart, perhaps, for some moments with Flagg — and yes, I will be returning to him eventually, too). All of these books were pleasant, and Eaton’s even had some dramatic scenes. But on the whole, reading these six titles was more about encountering old friends than making dramatic discoveries. I will begin my account with Torrey. I read two of his books recently: A Florida Sketch-Book (1894) and Footing It in Franconia (1901). Before I begin to share about each, I will briefly mention the provenance of my copies, both of which were likely first editions. Footing it in Franconia (upper left photo) bears a bookplate of Herbert S. Ardell. Herbert Stacy Ardell was born in 1878 and as of 1897, he lived at 221 Dean Street in Brooklyn. In 1895, he published “Among the Sioux Indians with a Camera” for Peterson Magazine. A Florida Sketch-Book was previously in the collections of Oxford Memorial Library in Oxford, New York; the book label shows a structure that matches well with the current library building.

On to my review of these two volumes. A Florida Sketch-Book was, well, rather a disappointment. Like Blatchley a few years later, Torrey approached Jacksonville by rail and spent his vacation in the northern portion of the state, mostly inland apart from some time around Daytona Beach. Ultimately, I think Torrey simply found the flat Florida landscape less enticing than, say, New Hampshire or even most of Massachusetts. Here is how he compared the Florida pine forest to his native woodlands of New England:

“Whether I followed the railway,—in many respects a pretty satisfactory method,—or some roundabout, aimless carriage road, a mile or two was generally enough. The country offers no temptation to pedestrian feats, nor does the imagination find its account in going farther and farther. For the reader is not to think of the flat-woods as in the least resembling a Northern forest, which at every turn opens before the visitor and beckons him forward. Beyond and behind, and on either side, the pine-woods are ever the same. It is this monotony, by the bye, this utter absence of landmarks, that makes it so unsafe for the stranger to wander far from the beaten track. The sand is deep, the sun is hot; one place is as good as another.”

Perhaps he saw literary merit in writing a book whose structure and quality generally mirrored the landscape he was writing about. Whether intended or not, his description of exploring the flat-woods matches my experience reading his book. There were a lot of birds seen and described (mostly woodland songbirds) and various encounters with natives whose conversational exchanges with Torrey fill intervening pages. But unlike Blatchley’s book, Torrey’s failed to transport me to north Florida. I closed the volume with little gained from the journey. Having read several other volumes he has written (and with a few more to go), I would say that he is capable of delightful, insightful prose, but not here.

Footing It in Franconia, on the other hand, was a much more delightful book. Here he trods far more familiar ground, in and around the Franconia Mountains of New Hampshire. Here, he shares his observations and reflections from a boat on Lonesome Lake on an autumn day:

“The lake is like a mirror, and I sit in the boat with the sun on my back (as comfortable as a butterfly), listening and looking. What else can I do? I have puUed out far enough to bring the top of Lafayette [Mountain] into view above the trees, and have put down the oars. The birds are mostly invisible. Chickadees can be heard talking among themselves, a flicker calls wicker, wicker, whatever that means, and once a kingfisher springs his rattle. Red squirrels seem to be ubiquitous, full of sauciness and chatter. How very often their clocks need winding! A few big dragon-flies are still shooting over the water. But the best thing of all is the place itself: the solitude, the brooding sky (the lake’s own, it seems to be), the solemn mountain top, the encircling forest, the musical woodsy stillness. The rowan trees were never so bright with berries. Here and there one still holds fidl of green leaves, with the ripe red clusters shining everywhere among them.

Here, the impatient, frustrated voice of Torrey in Florida is replaced by a more patient and contemplative one. Pausing to appreciate the landscape, Torrey draws the reader into it. Oh — and ironically, he also shares briefly about his visit to a Torreya Pine while in Florida years earlier. The memory emerges after sharing about a female entomologist he met during his travels:

“It was worth something to see a first-rate, thoroughly equipped ” insectarian ” at work and to hear her talk. I shoidd have been proud even to hold one of her smaller phials, but they were all adjusted beyond the need, or even the comfortable possibility, of such assistance. There was nothing for it but to play the looker-on and listener. In that part I hope I was less of a failure.

How many species already bear her name she has never told me. I suspect they are so numerous and so frequent that she herself can hardly keep track of them. Think of the pleasure of walking about the earth and being able to say, as an insect chirps, ” Listen ! that is one of my species, — named after me, you know.” Such specific honors, I say, are common in her case, — common almost to satiety. But to have a genus named for her, — that was glory of a different rank, glory that can never fall to the same person but once ; for generic names are unique. Once given, they are patented, as it were. They can never be used again — for genera, that is — in any branch of natural science. To our Franconia entomologist this honor came, by what seemed a poetic justice, in the Lepidoptera, the order in which she began her researches. Hers is a genus of moths. I trust they are not of the kind that ” corrupt.”

…sometimes, the lady will turn to me. “It is too bad you can never have a genus,” she will say in her bantering tone “the name is already taken up, you know.”

“Yes, indeed, I know it,” I answer her. An older member of the family, a — th cousin, carried off the prize many years ago, and the rest of us are left to get on as best we can, without the hope of such dignities. When I was in Florida I took pains to see the tree, — the family evergreen, we may call it. Though it is said to have an ill smell, it is handsome, and we count it an honor.

And there we leave the matter. Let the shoemaker stick to his last. Some of us were not bom to shine at badinage, or as collectors of beetles. For myself, in this bright September weather I have no ambitions. It is enough, I think, to be a follower of the road, breathing the breath of life and seeing the beauty of the world.”

Here I cannot help but compare Torrey’s desire to be a “follower of the road” to Blatchley’s desire to be a generalist naturalist and find joy in the moment. Both of them let go of visions of fame within a particular discipline, in favor of following their bliss. And both, interestingly enough, take a moment to contemplate the nature of death as a return to the whole of the cosmos. Here, Torrey reflects more positively on that transition, while on a birding outing to Mount Agassiz:

“Now and then, as I listen, I seem to hear a voice saying, ” Blessed are the dead.” I foretaste a something better than this separate, contracted, individual state of being which we call life, and to which in ordinary moods we cling so fondly. To drop back into the Universal, to lose life in order to find it, this would be heaven; and for the moment, with this musical woodsy silence in my ears, I am almost there. Yet it must be that I express myself awkwardly, for I am never so much a lover of earth as at such a moment. Life is good. I feel it so now. Fair are the white birch stems; fair are the gray-green poplars. This is my third day, and my spirit is getting in tune.”

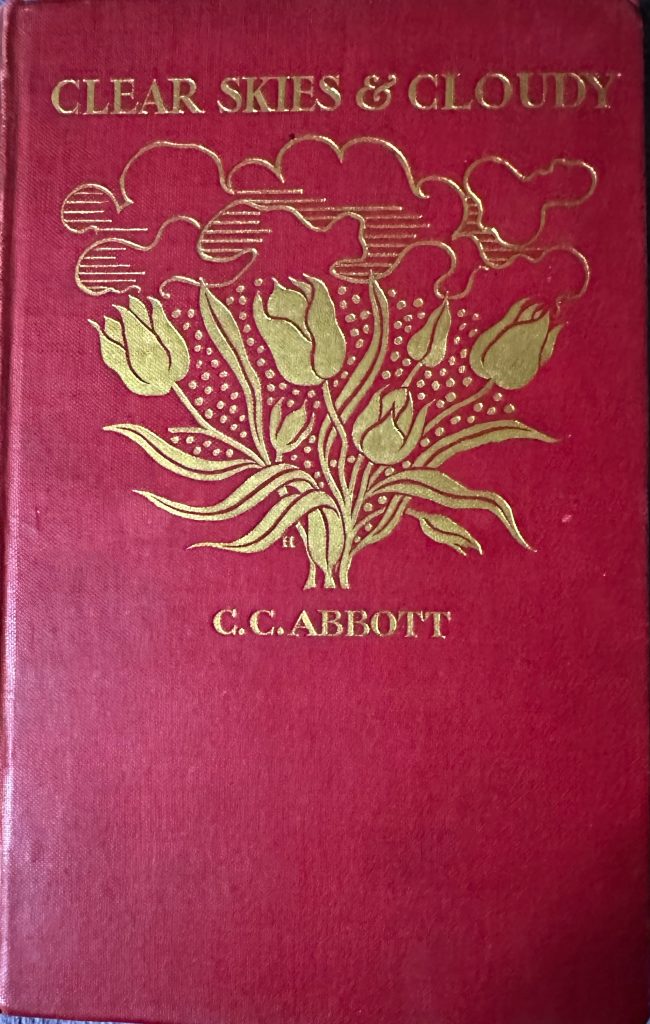

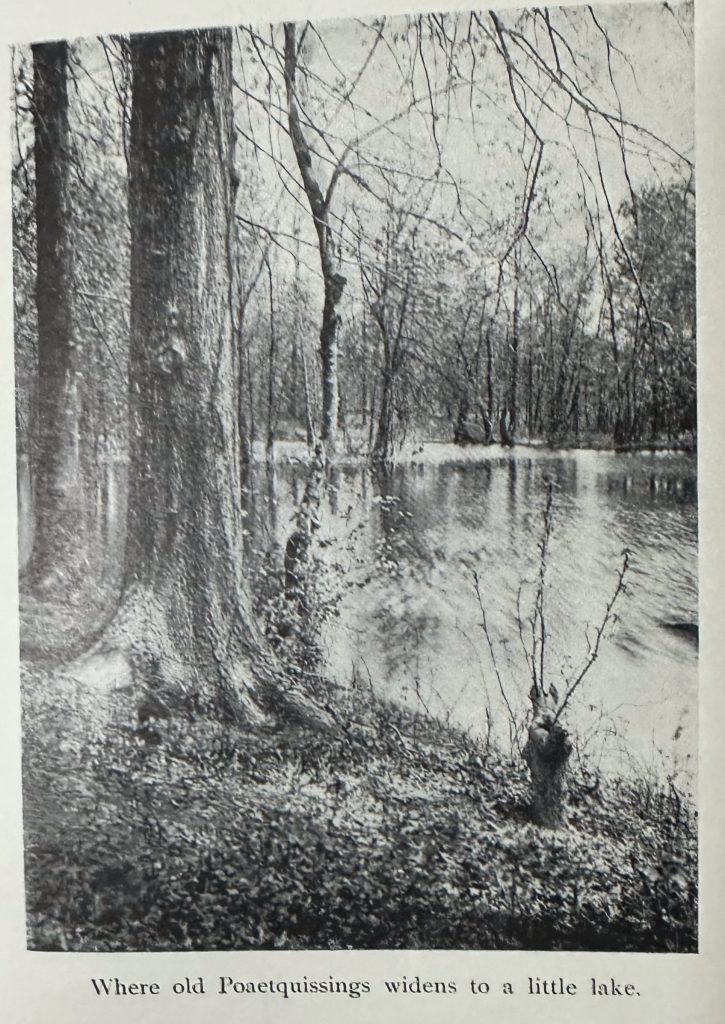

Onward to the next volume: Clear Skies & Cloudy by C. C.Abbott (1898). Easily the most elegant book of the lot, it has not only a stunning cover (above left) but lovely old photographs (unlike many other Abbott titles, which can include engravings but may not have any illustrations at all). Poaetquissings (above right) is a stream that flows through Abbott’s property named Three Beaches just south of Trenton, New Jersey. My copy of this book bears no marks of prior ownership and is in marvelous condition.

After two books of travel adventures from Torrey, Abbott offers an exploration of discoveries in his home place, defending that perspective with the observation that “The ever-present possibility of novelty is an incentive that should prove all-powerful, and nowhere is the world so worn out that the unexpected may not happen.” He further declares that “The best of what is out of doors is not always at arm’s length. Healthy enthusiasm is a rational phase of the spirit of adventure, but adventure does not necessarily mean distance, be it understood.” As Thoreau once remarked, “I have traveled a good deal in Concord.” Of course, it helps when one’s home place extends over many dozens of acres…

Making discoveries close to home can be a bit easier, too, when one is equipped with a Claude Lorraine Glass (also known as simply a Claude Glass), which I first encountered on page 68 of this book. A small black slightly concave mirror, it enabled the viewer to get a wider perspective of the landscape by bringing disparate elements closer together, while also showing more clearly the outlines of clouds. It is a largely forgotten tool that was widely used in the 1700s and 1800s by artists and travelers alike.

Here is one of my favorite passages from this book, on the art of listening to nature and the challenge of identifying the meaning behind sounds encountered in the woods:

“There is no such thing as a meaningless sound. It is a contradiction to speak of what we hear as having no significance, but the meaning of any sound may or may not be of importance to us. …To simply hear a sound is not all. To listen, to realize the full intent and purpose of every variation in the sound, to note the accompanying gesture with each characteristic utterance, whenever possible; in short, to appreciate the effort on an animal’s or bird’s part to interpret its own feelings, this is to listen intelligently, and in so doing to be taught a useful lesson in ornithology. There is profit, then, as well as pleasure in being abroad on a bright April morning like this, and noting, whether we stroll along the footpath way or stand by some one of the old oaks, whatsoever is to be heard on the hill-side.”

At a couple of points in his book, Abbott referred to the dramatic decline in bird numbers he had observed over the past few decades. Peregrine falcons and bald eagles had become rare, and even herons were much less common. “Time was when there were herons and heronries and stately white egrets along the river-shore, and the creeks teemed with wild fowl in season. It is a cause to be thankful, to-day, that the heron, a single heron, has given to this dismal day the charm of its presence….” At one point during a forest outing, Abbott noted sadly that

“It is hard to realize that time was when on this very spot there were birds by the thousands, and now often half a day goes by and not even one poor sparrow to make glad the fields. Many birds passed away with the trees, but not all. Birds have wit enough to accommodate themselves to very changed conditions, and would do so, but man will not permit. …Now, when it is almost, if not quite too late, an earnest cry is going up to spare the birds; but are not the fools too many and the wise too few to restor our one-time blessing? Spare what are left by all means, but what of those that are gone forever?”

Lest I leave the reader dispairing, I have to add here that not all moments in this book are as serious and dark as the one following the passage above, in which Abbott imagines a millstone he has found not as a testament to human progress, but a tombstone to all of nature that has been lost (p. 200). There is also this more whimsical moment, in which Abbott makes his way through a dense thicket in the woods, seeing the experience as an excellent cure for a naturalist’s boredom:

“…a wilderness of weeds of a single summer’s growth will well repay most careful exploration. It can offer stout resistance to your progress, and what may not hyssop and boneset and iron-weed and dudder conceal ? Your legs and arms held fast by the Gordian knot of greenbrier, you magnify, when helpless, every unexplained condition, and a foot-long garter-snake will give you a passing vision of a boa-constrictor, and mice will grow to wild-cats, before you see them scampering across your feet. If you would rid the day of possible monotony, push through a pathless thicket in the corner of some neglected field ; get scratched and pricked, and warmed by the effort, if not excitement, and believe ever after that the well-known country, as you thought it, is not so well known after all. Too seldom do we leave the beaten path and leap over the farmers’ fences.”

I will keep this little trick in mind the next outing in which I feel bored — as long as ticks and chiggers aren’t in season, at least.

My next book, Afield with the Seasons (1907) is by James Buckham (1858-1908). My copy bears an inscription to Claire Whitman Hathaway in Boston from [name not legible] on November 5th, 1932. I could not figure out Claire. There was a Claire May Whitman Hathaway who was born in Maine and died there 75 years later, in 1940. If she was given this book, she would have had to be living in Massachusetts at that time.

My next book, Afield with the Seasons (1907) is by James Buckham (1858-1908). My copy bears an inscription to Claire Whitman Hathaway in Boston from [name not legible] on November 5th, 1932. I could not figure out Claire. There was a Claire May Whitman Hathaway who was born in Maine and died there 75 years later, in 1940. If she was given this book, she would have had to be living in Massachusetts at that time.

Buckham’s writing is poetic, evocative, and sensorially rich. Here is an example:

“While the March trumpets are blowing, and the March sun is shining, there is a keen delight in skirting the ice edge of the woods. All the wild life within seems to come out on that sheltered side, especially in the early afternoon. Here, too, the earliest wild-flowers peep out, and the pasture or meadow grass first begins to grow green.

Perhaps you may walk in the shelter of the woods for miles in a sun-glow that sets you tingling; and while you hear the wind roaring overhead, lashing the woods and blowing the clouds against the sky, you might almost carry a lighted candle in your hand under that lee shelter, without seeing it extinguished.”

In this passage, Buckham makes a metaphorical link between cow paths and human dreams which I find rather intriguing:

“As the rambler strolls homeward along the old lane, he notes the many cow-paths that seam and furrow it, winding hither and thither, irrespective of parallels or of one another, approaching and then receding, like those plotted curves by which the modern psychologists represent the unconscious action of the human brain in dreams. Some of the paths are worn deep as ditches, with even deeper hoof-printed hollows in them, where the habit-forming cows have stepped for generations.”

While Buckham brings some basic scientific knowledge into his writing, ultimately he eschews it in favor of a deeper kind of knowing, the kind he describes in his last essay in the book as having characterized the American Indians:

“…we must not seek too strenuously for scientific explanations of the sounds in nature, if we would retain their mystical and poetic charm. I would rather not know exactly what makes the ice-bound lake whoop in the winter. The Indian knew the phenomenon best, because he knew least about it. I wish it were possible for us to still know many things in nature as the Indian knew them — mystically, feelingly, poetically, that is, instead of scientifically and materially.”

I am reminded once again of the challenge Burroughs posed for all nature writers: to maintain a sensibility at once both scientific and poetic. Reading over dozens of authors between 1850 and 1930, I am struck by the myriad ways in which they nearly all endeavor to do that, from deep pantheism and magic realism on one end to juxtaposed scientific description and poetry fragments on the other. In his longing to weave the two into his lived experience, Buckham reminds me considerably of Winthrop Packard.

The fifth book and fourth author is Skyline Camps by Walter Prichard Eaton (1922). In addition to writing books about nature around his home in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, Eaton also published this account of adventures out west, in newly established National Parks and Forests. He traveled with many others, adventuring in the wilderness on horseback and foot. Many chapters in this book concern adventures in Oregon (possibly on a single trip there), including exploring Glacier National Park, Crater Lake National Park, and the Northern Cascade Mountains, including an attempted ascent of snow-blanketed Mount Jefferson. His writing is effective and engaging if unspectacular. A wealthy Easterner by background, his exploits always involve a cast of many others, including a cook. He describes the landscape he experiences, identifying some of the birds and plants along the way. In places, he includes scientific names for the plants, though he rarely does more than name and briefly describe what he sees. I enjoyed the book and was glad I had read it, but I reached the end without encountering a single passage worth sharing here. I am finding that travel nature books can be a mixed bag. For those who dig in deep and intensely engage with a new place (such as Blatchley in Florida), the result can be fascinating. For other writers, just passing through and seeing what they can along the way (like Torrey in Florida and Eaton in Oregon), the result does not have the power of nature writing by authors who have inhabited and rambled through in their natural places for many years. Here I am thinking of Burroughs in the Catskills, Muir in the Sierras, Mills in the Rockies, and Abbott along the Delaware.

My last, and latest, visit was with Ernest Ingersoll’s Nature’s Calendar (1900). Above left is an image of the lovely dragonfly cover (in the case of my copy, looking a bit bedraggled), while a portrait of Ingersoll is above right. In the middle, you can get a sense of the book’s layout. Each page includes extensive white space in the margins, both beside and below the text. “…regard the printed part as nothing more than my beginning,“, Ingersoll explains to the reader, “and…complete it and correct it for your own locality in the blank spaces left to you for that purpose.” The reader is tasked with recording what they observe, given Ingersoll’s definition of observation as “the faculty of keeping open at the same time both the eyes and the mind.” Of course, to get the reader to do that requires overcoming hesitation amongst those uncomfortable with writing in their books. So Ingersoll does his best to encourage the reader further, noting that “It is well known to book-lovers and to the collectors of rare volumes that the value of an old book is enhanced in most cases when its margins show annotations by the owner; and that such books more often than others are kept as precious heirlooms…” Mary Bradley Allen, who received this book on September 17th, 1900 according to the flyleaf, never recorded anything else in the book, however, despite Ingersoll’s entreaties.

The book gets off to a slow start, though starting in January, when so much of nature is hidden or asleep, makes this somewhat expected. Throughout the volume, Ingersoll relied heavily on the observations of others, including Thoreau, Burroughs, Abbott, Cram, Packard, Wright, Allen, Merriam, Flagg, and others. The text itself points out what may be experienced each month, assuming one is in southern New England or thereabouts. As the work continues, the prose seems to become a bit less wooden (perhaps I got used to it over time?), and Ingersoll offers helpful guidance to the novice naturalist. In the text for May, for example, he provides some basic recommendations for the would-be birder, beginning with the idea that birds ought to be approached quietly to avoid scaring them away. His birding advice includes this caveat:

“Few windows open so pleasantly into the temple of nature as that through which we look when we study the grace and beauty of birds. We should fall short of the highest advantage, however, if we learned merely to recognize the birds apart, and failed to get some idea of the larger world of which they are but one delightful feature.”

What new realization, ultimately, would tyro naturalists stand to gain by making their way through the year with Ingersoll as a guide? As he closed out the volume, he offered this parting prospect in a somewhat comma-tose fashion:

“We have now followed the circle of year round to its calendar, beginning in January. and have found that it all moves together, the revival of vegetation under the spring sun being the signal for the awakening of animal life and the renewal of its energies, and its progress from leaf to flower, and then to fruit, being accompanied by the development of the various creatures that depend upon it for food. Each year is a grand illustration of the interdependence of all nature; of the exact adjustment of each creature to the other creatures of its locality and to their surroundings, and of the uniformity of law.”