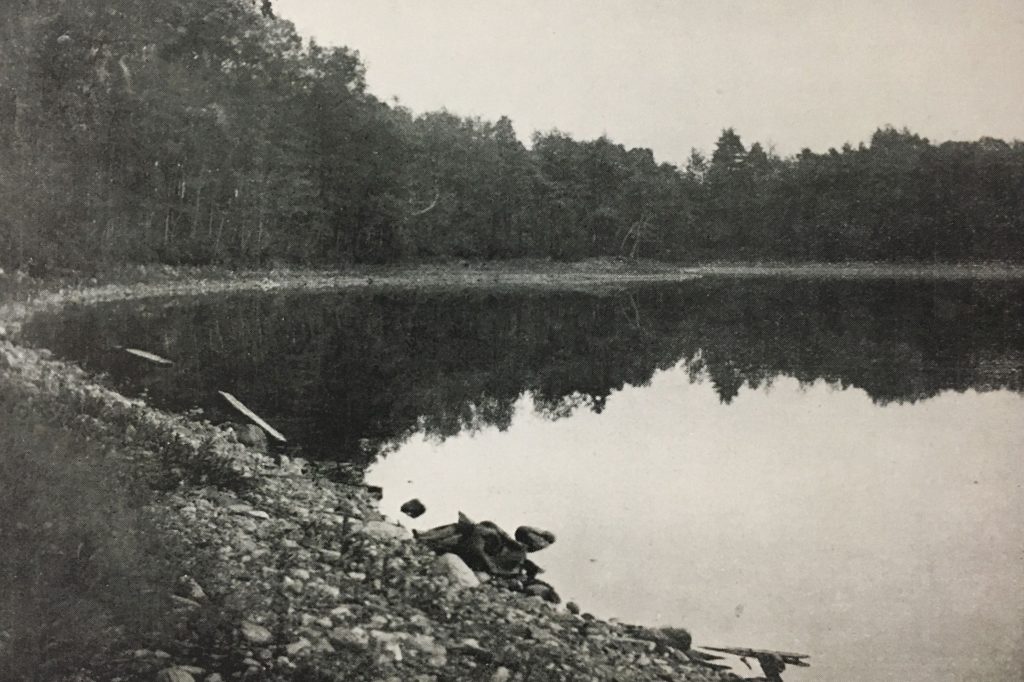

Chin deep in [the] middle [of Walden Pond], you begin to feel that you know the pond. In a sense you are its eye and look upon the world as it does. Day breaks for the swimmer as it does for Walden, and the flash of the sun above the wood to eastward warms you both with the same sudden sweep of its August fire. In the same sense you are pond’s ear and hear as it does. The morning rustle of the trees, shaking the dark from their boughs, comes to you as a clear ecstasy, and you think you can hear the wan tinkling of the invisible feet of fairy mists as they leap sunward from the surface and vanish in the day. Over the wood comes the intermittent pulse of Concord waking, and by fainter reverberations the pond knows that Lincoln and more distant villages are astir. Then the first train of the day crashes by the southern margin and stuns the tympanum with a vast avalanche of uproar.

THIS IS ONE OF THE MOST EVOCATIVE AND MYSTICAL PASSAGES IN PACKARD’S BOOK. If we can overlook the allusion to fairies, it is really quite beautiful; a lone swimmer at Walden’s center, who becomes the pond’s own ear and eye. I have read many accounts of visiting Walden (and have ventured there a few times myself, including one fairly magical early morning when the pond was wreathed in fog). Yet Packard manages to see the place from a different vantage point than anyone else, and to considerable effect. Other sections of “Literary Pilgrimages of a Naturalist,” while failing to reach the heights of that one, still do a noteworthy job of capturing the rich flora of an hillside pasture near the birthplace of John Greenleaf Whittier:

Kenoza Lake opens two wide blue eyes at your feet, and all along beneath you roll bare, round-topped hills sloping down to dark woods and scattered fields, as unspoiled by man as in Whittier’s days. The making of farms does not spoil the beauty of a county; it adds to it. It is the making of cities that spells havoc and desolation. Through the pasture, up the steep slopes to the summit of Job’s Hill, that seems so bare at first glimpse, climb all the lovely pasture things to revel in the free winds. Foremost of these is the steeplebush, prim Puritan of the open wold, erect, trying to be just drab and green and precise, but blushing to the top of his steeple because the pink wild roses have insisted on dancing with him up the hill, their cheeks rosy with the wind, their arms twined round one another at first, then around him as well.

I THINK WE HAD BEST STOP THERE. I have read writers that anthropomorphize wildlife — deer, foxes, perhaps even an insect or two. But until I encountered Packard, I never would have guessed it possible to imbue wildflowers with decidedly human behaviors and feelings. Packard describes birds and butterflies at times, too, but his specialty is flowers. And what strange descriptions they are. Consider Bouncing Bet, a.k.a. soapweed, Saponaria officinalis. I’ll bet the reader has never encountered it described as a wanton amidst New England Puritans before:

Here, too, rioting through the old time flower gardens and out of them, dancing and gossiping by the roadside and in the field, sending rich perfume across lots as a dare to us all, is Bouncing-Bet. I cannot think of this amorous, buxom beauty as having been allowed to come with a shipload of serious, praying Pilgrims or any later expedition of stern-visaged Puritans. I believe she was a stow-away and when she did reach New England danced blithely across the gang plank and took up her abode wherever she saw fit. Thus she does today. All over the Cape she strays, a common roadside weed and a beauty of the gardens at once.

And then there is his odd account of the seaside goldenrod with its “bare toes”:

Of these wild flowers the seaside goldenrod is most profuse. Pasture-born like the cedars, it too loves the sea and crowds to its very edge like the people at Revere and Nantasket, so close indeed that at high tides the smelt and young herring, swimming in silver shoals, nibble at the bare toes the plants dabble in the water. You may know this even if you do not see the nibblers, for the plants quiver and shake with suppressed laughter at being thus tickled.

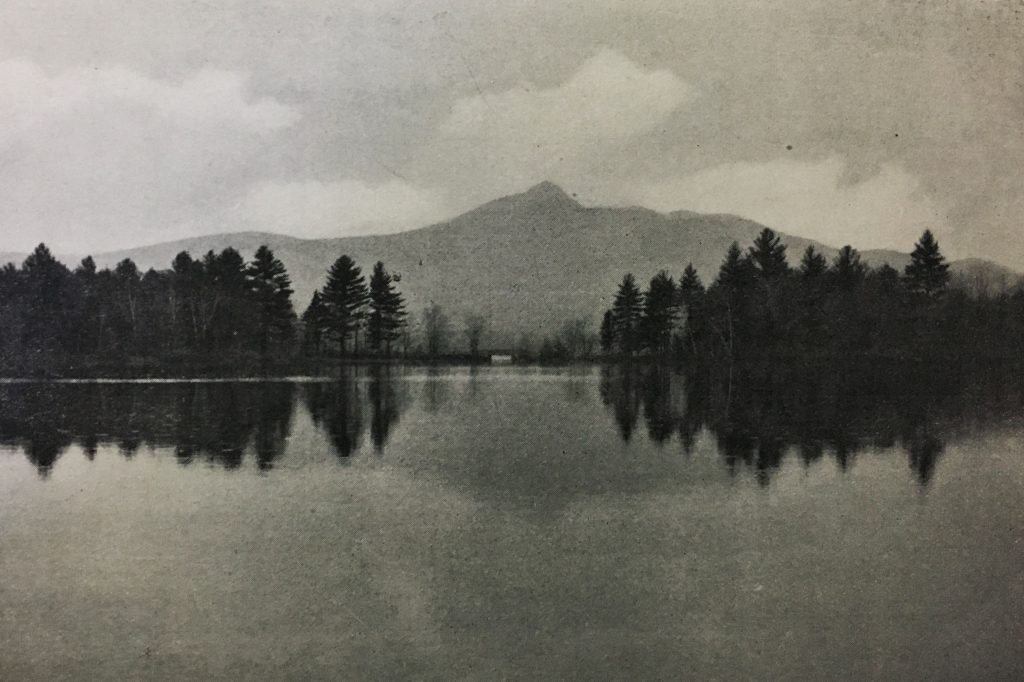

TIME TO ADD “FLOWER TICKLING” TO MY LIST OF ODD NATURAL HISTORY ACTIVITIES I HAVEN’T YET ATTEMPTED. But if we can overlook Packard’s strange botanical fancies (and fantasies), we are left with a robust, serviceable (if not always inspiring) volume of the author’s rambles in the landscapes of writers of yore. In addition to Thoreau and Whittier, these include Frank Bolles and Celia Thaxter. I will close with a lovely text description of the interior reaches of Thaxter’s Appledore Island, followed by a 1911 photograph of Boles’ beloved Lake Chocorua, with the mountain beyond.

Often in the tiny valleys in the heart of [Appledore] Island, surrounded by its dense shrubbery, you lose sight of the sea, but you cannot forget it. However still the day, you can still hear the deep breathing of the tides, sighing as they sleep, and a mystical murmur running through the swish of the breakers, that is the song of the deep sea waves, riding steadily in shore, ruffled but in no wise impeded by the west winds that vainly press them in the contrary direction. However rich the perfume of the clematis the wind brings with it the cool, soothing odor that is born of wild gardens deep in the brine and loosed with nascent oxygen as the curling wave crushes to a smother of white foam. It may be that the breathing of this nascent oxygen and the unknown life-giving principles in this deep sea odor gives the plants of Appledore their vigor and luxuriance of growth. Certainly it would not seem to be the soil that does it. Down on the westward shore of the island, in an angle of the white granite, where there was but a thin crevice for its roots and no sign of humus, I found a single yarrow growing. Its leaves were so luxuriant, so fern-like and beautiful, such feathery fronds of soft, rich green as to make one, though knowing it but yarrow, yet half believe it a tropic fern by some strange chance transported to the rugged ledges of the lonely island. With something in the air, and perhaps in the granite, that makes this common roadside plant develop such luxuriance. it is no wonder that the other common pasture folk, goldenrod and aster, morning glory and wild parsnip, and a dozen others, growing in abundant soil in the tiny levels and hollows, are taller and fuller of leaf and petal than elsewhere. In the richness and beauty of the yarrow leaves growing in the very hollow of the granite’s hand, as in the height and splendor of the Shirley poppies in the little garden, one seems to find a parallel to Celia Thaxter, whose own character, nurtured on the same sea air, sheltered in the hollow hand of the same granite, grew equally rich and beautiful.

FINALLY, A FEW WORDS ABOUT MY BOOK ITSELF. This time, I read a first edition hardcover (was there ever another edition published?), fairly worn with library use. It spent many of its past days as 917.4 / P12 on a shelf at the library of the State Normal School in Valley City , North Dakota, about a third of the way from Fargo to Bismarck. I am a bit jealous of my book in that regard: North Dakota is one of only two states (along with Alaska) that I haven’t visited yet. According to the Date Due page (still present), the book was last checked out in November and December of 1967, and sometime after that was withdrawn from Allen Memorial Library of Valley City University (which, I suspect, is what the State Normal School later became). The volume’s most notable feature is its gilt cover, gold on a red cloth background: