As spring advances, the observant naturalist notices an array of flowers coming into bloom along roadsides and forest paths. One flower blooming now that is easily missed belongs to a leafy vine that should not be overlooked: poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Few of our native plants have as black a reputation as this member of the cashew family, frequently encountered along forest edges, roadsides, and in other disturbed areas. After all, how many other native plants are the subject of rhymes about their dangers? “Leaflets three / let them be.”

As spring advances, the observant naturalist notices an array of flowers coming into bloom along roadsides and forest paths. One flower blooming now that is easily missed belongs to a leafy vine that should not be overlooked: poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Few of our native plants have as black a reputation as this member of the cashew family, frequently encountered along forest edges, roadsides, and in other disturbed areas. After all, how many other native plants are the subject of rhymes about their dangers? “Leaflets three / let them be.”

Certainly poison ivy’s reputation is, to some extent, richly deserved. Unless you happen to belong to the twenty percent or so of the population that can handle poison ivy plants with impunity, contact with them can have memorable but unpleasant consequences. Poison ivy’s shiny leaves and hairy vines both contain an oily sap, urushiol, which can penetrate the skin and provoke an allergic reaction that produces a rash, blisters, intense itchiness, and general misery. Some people are so sensitive to this allergen that merely coming into close proximity with poison ivy may be enough to have an effect.

But with respect for those so severely afflicted, poison ivy is actually a highly beneficial plant for our native wildlife. Strangely enough, humans appear to be almost its only animal victims. White-tailed deer actually forage preferentially on poison ivy leaves. But birds are the main beneficiaries. Woodpeckers, flickers, grouse, pheasants, bobwhites, and warblers are all drawn to poison ivy’s small, spherical, tan fruits in the fall and winter. The seeds pass through these birds’ digestive tracts, helping to spread poison ivy far and wide. To aid in its own dispersal, poison ivy practices foliar fruit flagging, a technique also used by flowering dogwood. In the autumn, poison ivy leaves turn to blazing shades of red and gold. This bright coloration signals to the birds that food is available.

This early in the year, though, poison ivy sports bright-green, shiny leaves. Beneath the leaves hang panicles (dense, branching clusters) of minute, greenish-white flowers. In close-up photographs (such as the one available about halfway down on the left on this page), the minute flowers with their five petals forming a star and their white and yellow pistils and stamens look almost elegant. But to appreciate them under a hand lens requires putting the hands, arms, and face at too great a risk to be worthwhile, in this writer’s opinion.

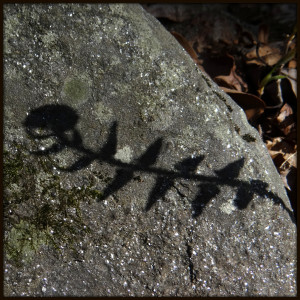

A hardy survivor, poison ivy spreads not only by seeds, but vegetatively as well. The vines that appear to be hairy are, in fact, covered with rootlets, ready to take hold of a tree trunk or burrow into the soil. Considering its predilection for covering extensive ground, this writer confesses to eying the plant with suspicion when encountering it in the yard, despite its benefits to deer and songbirds. But inevitably, it is easiest to let a few vines be, provided they not overstep their bounds. After all, poison ivy is here to stay.

In fact, recent studies of forest plant response to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels indicate that it leads to a significant increase in poison ivy growth — on the order of 150 percent. This result is known as the “carbon dioxide fertilization effect.” Accompanying that surge, it appears that the increased carbon dioxide also enables the poison ivy to produce a more virulent strain of urushiol, leading to worse allergic reactions than are presently experienced. At least we can look forward to the day when the poison ivy begins to choke out our invasive plant species — kudzu, privet, honeysuckle, wisteria, and others. That is some small consolation, perhaps, at least for the die-hard naturalists out there.

This article was originally published on May 2, 2010.

As spring advances, the observant naturalist notices an array of flowers coming into bloom along roadsides and forest paths. One flower blooming now that is easily missed belongs to a leafy vine that should not be overlooked: poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Few of our native plants have as black a reputation as this member of the cashew family, frequently encountered along forest edges, roadsides, and in other disturbed areas. After all, how many other native plants are the subject of rhymes about their dangers? “Leaflets three / let them be.”

As spring advances, the observant naturalist notices an array of flowers coming into bloom along roadsides and forest paths. One flower blooming now that is easily missed belongs to a leafy vine that should not be overlooked: poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). Few of our native plants have as black a reputation as this member of the cashew family, frequently encountered along forest edges, roadsides, and in other disturbed areas. After all, how many other native plants are the subject of rhymes about their dangers? “Leaflets three / let them be.”