Sometimes nature really surprises us. We naturalists fill our shelves with field guides, and their minds with Latin names for local species of animals and plants. We venture into the woods looking for the first spring ephemeral wildflower in bloom, and listening for the first call of a red-wing blackbird at a nearby marsh. After a bout of rain, we take pleasure in the more unusual pastime of identification and, for the more daring, consumption of various fungi.

Sometimes nature really surprises us. We naturalists fill our shelves with field guides, and their minds with Latin names for local species of animals and plants. We venture into the woods looking for the first spring ephemeral wildflower in bloom, and listening for the first call of a red-wing blackbird at a nearby marsh. After a bout of rain, we take pleasure in the more unusual pastime of identification and, for the more daring, consumption of various fungi.

But sometimes we chance upon something so foreign, so peculiar, that it truly humbles us. All we can do is fall back on Shakespeare’s famous remark that “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” The cedar apple rust gall definitely fits into that category.

For all the field guides out there, precious few are devoted to plant galls. These strange constructions of living plant tissue, formed in response to invading parasites such as insects and fungi, somehow fall between the cracks. They are neither healthy plant specimens nor parasites themselves, but instead a product of the two, in which a parasitic organism somehow takes control of the plant’s growth and warps it to its own ends. Often, the gall serves as home for a developing insect, and protection from predators as well. In the case of the cedar apple rust gall, th gall is part of the bizarre fungal life cycle.

The cedar apple rust gall receives its name from the fact that the fungus responsible, Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae, lives alternately on cedars and apple trees. Fungal spores invade a eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) and live within the host plant’s tissues for up to two years. During that time, they cause brown galls to develop on the tree. These galls grow to a couple of inches in diameter and then, after a series of spring rains, they burst open, releasing gelatinous orange tendrils. The tendrils, in turn, form and release spores to be carried up to three miles by the wind.

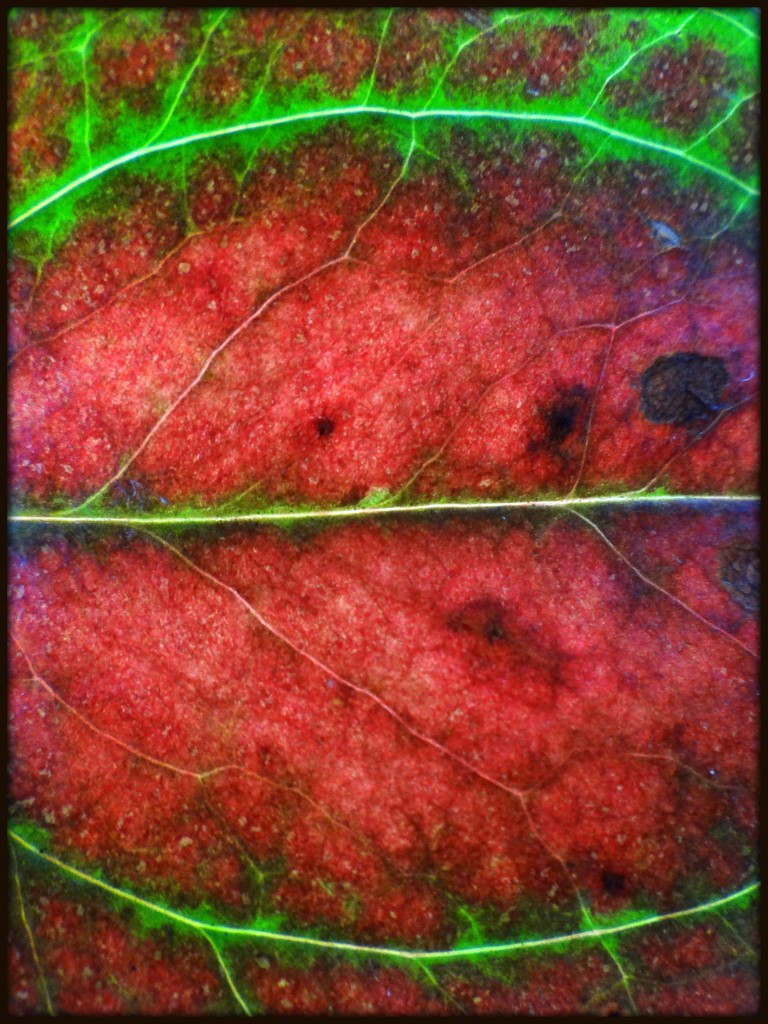

But these spores do not re-infect red cedar trees. Instead, they invade apple trees, where they produce yellow and orange lesions on leaves and fruit. Black pimple-like bodies form in these lesions and release a sticky substance that attracts insects. In a peculiar parallel to pollination, the insects carry fungal reproductive cells from one rust spot to another, fertilizing the fungus. The fungus then grows through the infected apple leaf, forming reproductive structures that release new spores that invade red cedars, continuing the cycle.

The cedar oak gall is a serious disease of apples. As such, I suspect it is quite familar to most orchardists. But to this naturalist, the sight of its bright orange tendrils was most unexpected — alien, even. It was a pleasant surprise, warding off any incipient complacency. There is still a lot out there left to discover. A 2007 field guide to galls of California and the Western US (available here), which appears to be the only gall guide in print for anywhere in this country, included thirty-five galls “new to science”. That figure represented more than ten percent of the galls covered in that book. Amazing.

This article was originally published on April 6, 2010.

Sometimes nature really surprises us. We naturalists fill our shelves with field guides, and their minds with Latin names for local species of animals and plants. We venture into the woods looking for the first spring ephemeral wildflower in bloom, and listening for the first call of a red-wing blackbird at a nearby marsh. After a bout of rain, we take pleasure in the more unusual pastime of identification and, for the more daring, consumption of various fungi.

Sometimes nature really surprises us. We naturalists fill our shelves with field guides, and their minds with Latin names for local species of animals and plants. We venture into the woods looking for the first spring ephemeral wildflower in bloom, and listening for the first call of a red-wing blackbird at a nearby marsh. After a bout of rain, we take pleasure in the more unusual pastime of identification and, for the more daring, consumption of various fungi.