The next fortnight was not productive of many adventures or noteworthy incidents, though it contained plenty of hard work. Our track led across into the head of the San Luis Park, and so on down to Saguache — a Mexican town near the Rio Grande. There was a pleasant bit of natural history picked up along here, though.

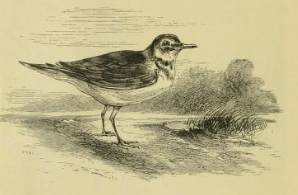

The plover of these interior valleys does not seem to care for marshes, like the most of his race, but haunts the dry uplands. It is closely related to the golden plover, and is named in books Aegialitis montanus. A flock of these plovers dropped down on the plain one day, and I determined to get them for dinner, if possible. Jumping off my horse — who would stand stock-still wherever I left him— I approached to where they had dropped, and finally caught sight of one by distinguishing the dark dot of its eye against the light-tinted surface of the ground. Even then I really could not follow with my eye the outline of the bird’s body, so closely did the colors of the plumage agree with the white sand and dry grass. I shot it ; then found another, shot that; and so on until all were killed, none of them flying away, because their ” instinct,” or habit of thought, had taught them that when danger threatened they must invariably keep quiet ; movement would be exposure, and exposure would be fatal. I and my gun formed a danger they had had no experience of, and here their inherited “instinct” was at fault. When I had shot them I was unable, with he most careful searching, to find all the dead birds.

Ernest Ingersol’s early book, Knocking About the Rockies, chronicles two trips he took into the Rockies (1874 and 1877), accompanying scientific and surveying expeditions. His flair for natural history (he would go on to write a dozen works in the “nature” realm, one previously covered in this blog, with several more awaiting reading) led me to this book and his subsequent one about travels by train through the Rockies (The Crest of the Continent, 1885). I eagerly anticipated observations and reflections on the wildlife of the region. And he delivered well, including several allusions to Thoreau. What I had not reckoned on was that many of them would take a culinary turn. Here, “a pleasant bit of natural history” includes identifying a new bird species and then shooting it for dinner. Or not even dinner. Maybe just as a specimen to observe more closely, or possibly just because his gun is handy?

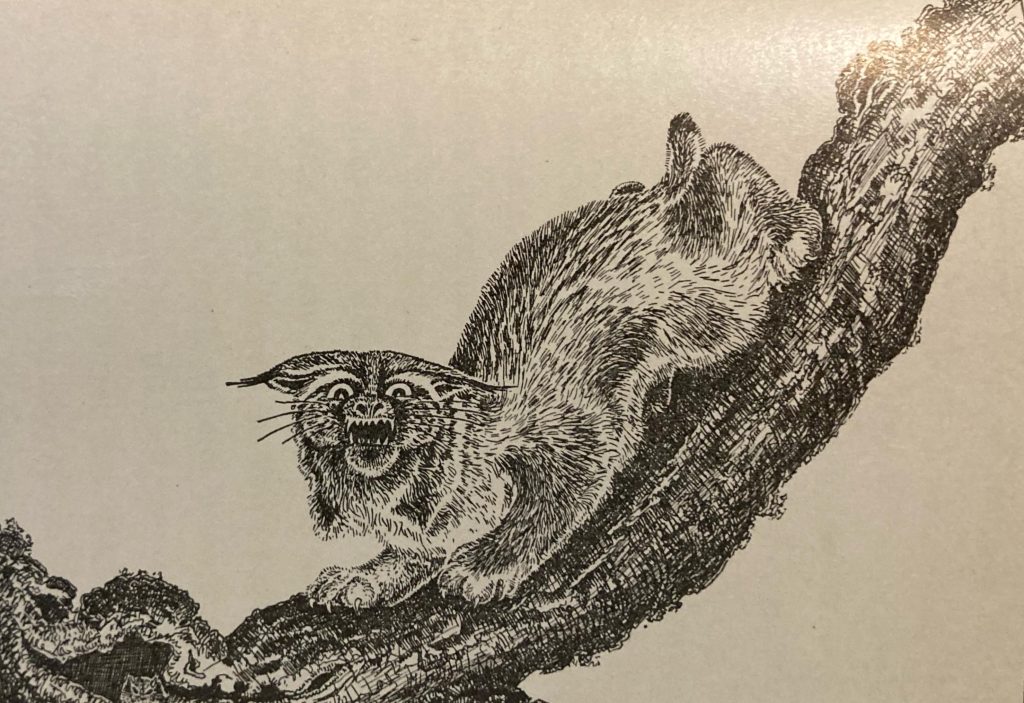

Climbing a high point back of our tents, which were in the midst of a sage-brush flat, close to the river, I had a queer little bit of good luck one evening. It was just at nightfall, and as I reached the top a large owl came swooping down and perched on a crag some distance off. Drawing my revolver, I held it up and walked slowly nearer, expecting neither to get within range nor hit the bird if I fired; but he let me get so near that at last, about thirty yards off, I blazed away, and down came the owl. Rushing up, I could see him lying in the brush a little way below; but it was some time before I got courage enough to reach down and take hold of him, for a bite or talon-grasp from a wounded owl is no joke. He proved to be stone-dead, and it was a long time before I found out the bloodless wound, the bullet having gone in at the base of the skull and out of the open mouth, without tearing any of the feathers. He was a fine barred or “cat” owl, about two feet long.

I am sure the owl did not appreciate this “queer little bit of good luck”.

It is easy, in hindsight, to condemn this behavior in a would-be naturalist. Of course, the great bird illustrator John James Audubon shot all his bird specimens, too, attaching their lifeless bodies to branches in order to draw them. While one or more cameras accompanied these expeditions — several of the illustrations in the book are engravings from photographs — photography had not advanced enough yet to make close-up images of wildlife possible. The understood technique for close study of animals was to shoot them first. This was slowly changing, as birders began carrying opera glasses into the field instead. And Ingersoll, himself, would rein in his hunting proclivities in his later volumes. Finally, it is to be noted that, in order to travel light and save money, the expeditions carried little food, intending that protein needs be satisfied with hunting and trapping.

Now that we have gotten that aspect of this book out of the way, we can sit back and enjoy some lovely late 19th Century prose about the wilds of the Colorado Rockies (including some delightful geological terms). Here is Grand Lake as seen (more like imagined, actually) from a mountaintop, sounding truly grand indeed:

From this pinnacle, in daylight, there is visible a picture of blue mountains whose sharp, serrated outline indicates a portion of the main range in front of Long’s Peak. Among those immutable yet ever-changing bulwarks lies a lake in a circle of guardian peaks whose heads tower thousands of feet above it, and whose bases meet no one knows how far below the surface of its dark waters. It is Grand Lake, a spot taboo among Indians and mysterious to white men. The scenery is primeval and wild beyond description: Roundtop is one mountain at least that has suffered no desecration since the ice ploughed its furrowed sides. The lake itself lies in the trough of a glacier basin, and its western barrier is an old terminal moraine, striking evidences of glacial action occurring on all sides in the scored cliffs and lateral moraines that hem it in. Its extent is about two miles by three, and its greatest depth unfathomable with a line six hundred feet in length. The water is cold, and clear near the shore, but of inky blackness in the middle. In the reflection usually pictured upon its calm bosom all the cloud-crowned heads about it meet in solemn conclave; but not seldom, and with little warning, furious winds sweep down and lash its lazy waters till the waves vie with each other in terrible energy.

Ingersoll clearly had a passion for climbing peaks and gazing out upon the landscape from their heights. Here, he waxes religious in extolling the glories of just such an experience:

However interesting it might prove, time forbids even to suggest all that meets the eye and is implanted in the memory while one is sitting for two or three hours on a peak of the Rocky Mountains — the surprising clearness of the air, so that your vision penetrates a hundred and fifty miles; the steady gale of wind sucked up from the heated valleys ; the frost and lightning shattered fragments of rock incrusted with lichens, orange and green and drab and white; the miniature mountains and scheme of drainage spread before you; the bright blue and yellow mats of moss-blossoms ; the herds of big-horned sheep, unconscious of your watching; the hawks leisurely sailing their vast aerial circles level with your eye ; the shadows of the clouds chasing each other across the landscape; the clouds and the azure dome itself; the purple, snow-embroidered horizon of mountains, “upholding heaven, holding down earth.” I can no more express with leaden types the ineffable, intangible ghost and grace of such an experience than I can weigh out to you the ozone that empurples the dust raised by the play of the antelopes in yonder amethyst valley. Moses need have chosen no particular mountain whereon to receive his inspiration. The divine Heaven approaches very near all these peaks.

Not that Ingersoll found every experience on his travels filled him with awe and wonder. Here, he expresses quite different sentiments in a dark spruce forest in the mountains:

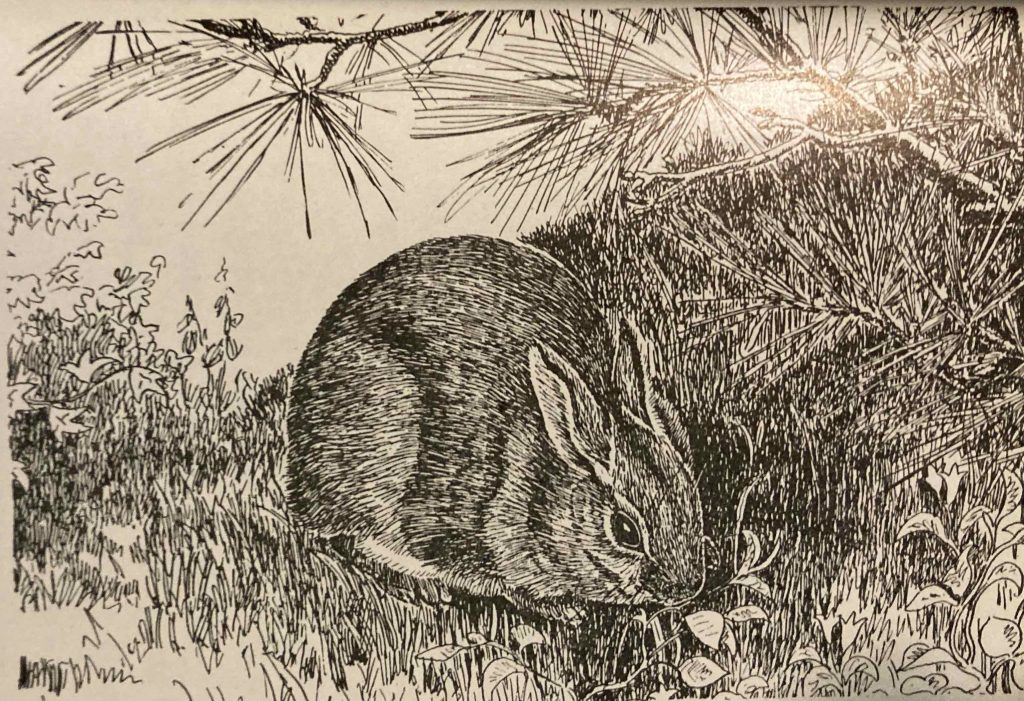

What a sombre world that of the pine-woods is! None of the cheerfulness of the ash and maple groves — the alternation of sunlight and changing shadow, rustling leaves and fragrant shrubbery underneath, variety of foliage and bark on which to rest the jaded eye, exciting curiosity and delight: only the straight, upright trunks; the colorless, dusty ground; the dense masses of dead green, each mass a repetition of another; the scraggy skeletons of dead trees, all their bare limbs drooping in lamentation. The sound of the wind in the pines is equally grewsome. If the breeze be light, you hear a low, melancholy monody; if stronger, a hushed kind of sighing; when the hurricane lays his hand upon them the groaning trees wail out in awful agony, and, racked beyond endurance, cast themselves headlong to the stony ground. At such times each particular fibre of the pine’s body seems resonant with pain, and the straining branches literally shriek. This is not mere fancy, but something quite different from anything to be observed in hardwood forests. There the tempest roars; here it howls. I do not think the idea of the Banshee spirits could have arisen elsewhere than among the pines ; nor that any mythology growing up among people inhabiting these forests could have omitted such supernatural beings from its theogony.

But do not conclude that the gloom of the pine-woods clouded our spirits. So many trees had fallen where our tents were pitched that the sunshine peered down there, and at night the moon looked in upon us, rising weirdly over a vista of dead and lonely tree-tops. Then, too, the brook was always singing in our ears — absolutely singing! The sound of the incessant tumble of the water and boiling of the eddies made a heavy undertone, like the surf of the sea; but the breaking of the current over the higher rocks and the leaping of the foam down the cataracts produced a distinctly musical sound — a mystical ringing of sweet-toned bells. There is no mistaking this metallic melody, this clashing of tiny cymbals, and it must be this miniature blithe harmony that fine ears have heard on the beach in summer where the surf breaks gently.

While Ingersoll viewed these mountains, forests, and grasslands with rapture, he also saw what would soon be. Observing extensive grasslands at the feet of the mountain peaks, Ingersoll remarked that “Here are the future pastures for millions of cattle, and they are sure to be occupied.” I find it strange that for all the natural beauty he witnessed, he seemed resigned to (or even somewhat enthusiastic about) a future in which the Rockies would be dramatically modified — and the bison would nearly go extinct.