Many other experiments I recorded which I will not inflict on the reader in detail.

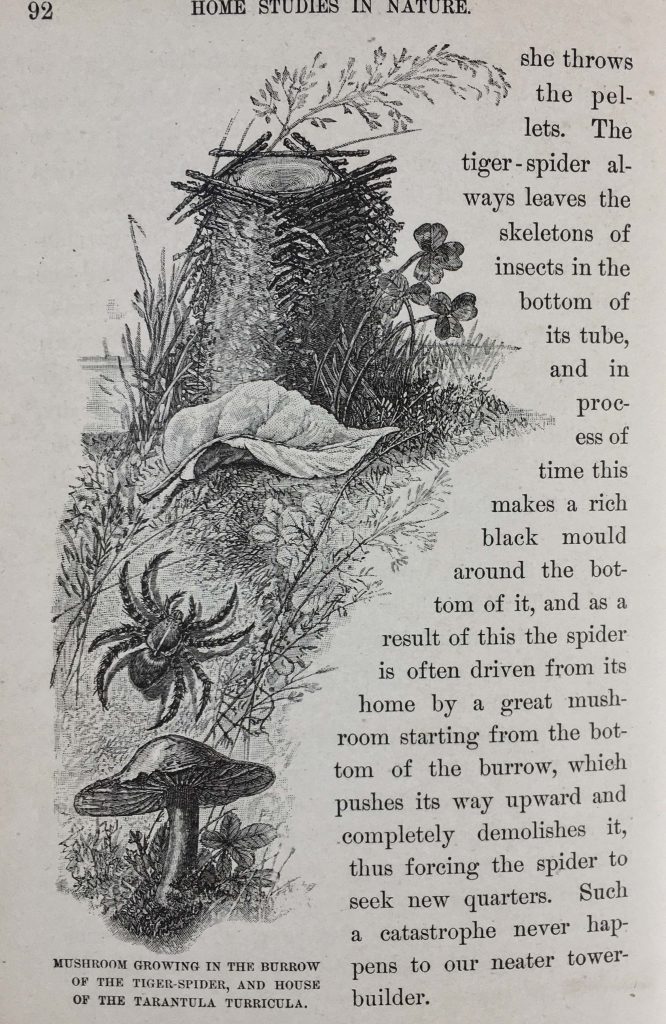

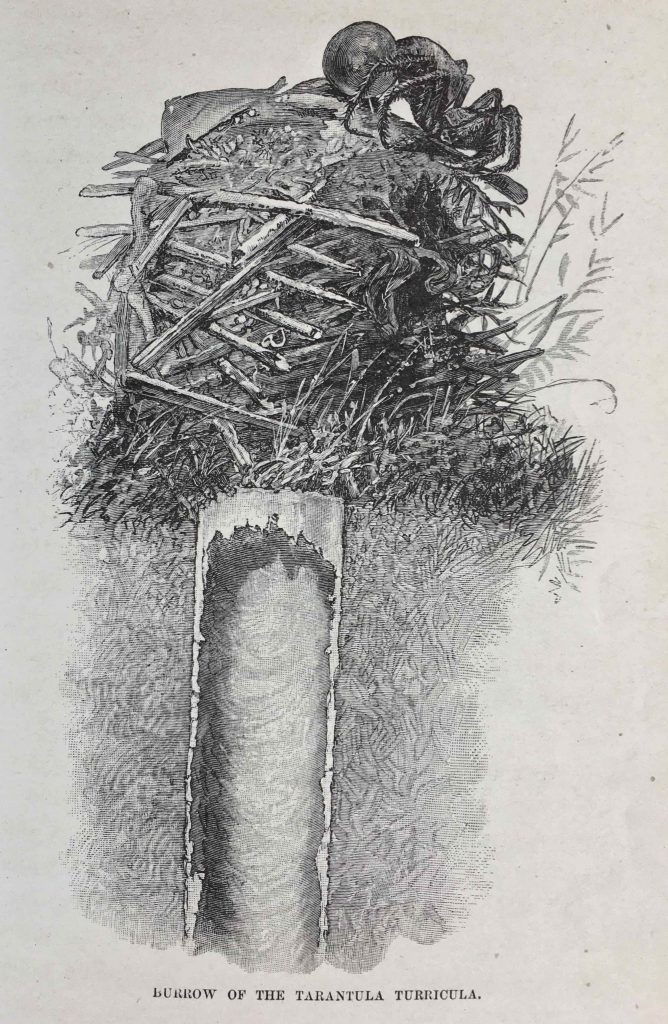

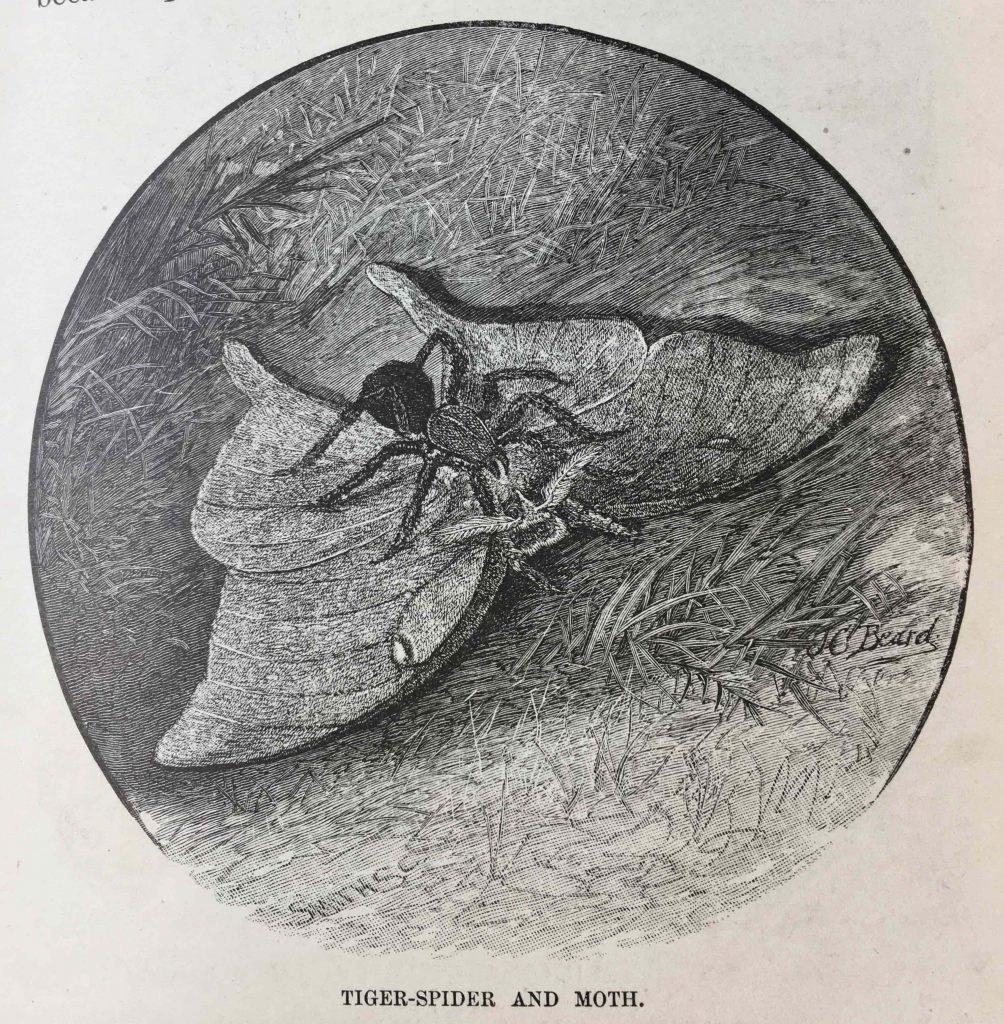

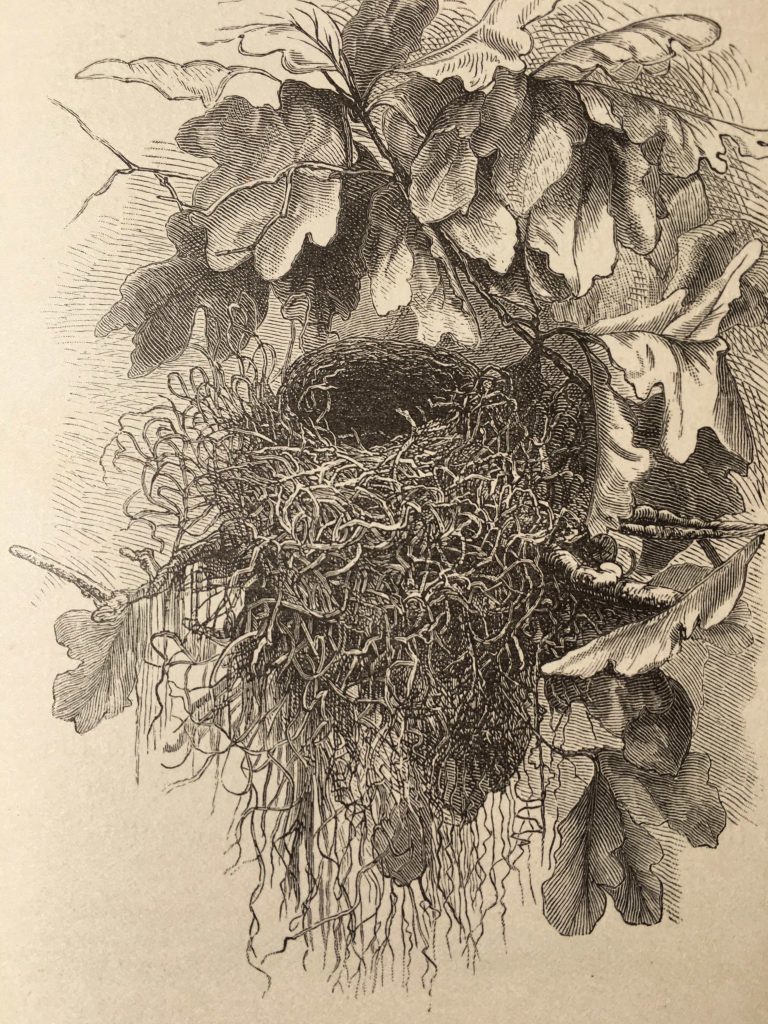

AFTER A FEW ENCHANTING CHAPTERS ABOUT BIRDS, TREAT REVEALS HERSELF TO BE A HIGHLY DEDICATED, RIGOROUS FIELD BIOLOGIST. Treat begins the second section of her book, on the Habits of Insects, by observing that “I sometimes think the more I limit myself to a small area, the more novelties and discoveries I make in natural history. My observations for the past four summers have been almost wholly confined to an acre of ground in the heart of a noisy town” (Vineland, New Jersey). In that chapter and the ensuing ones, Treat reports on her careful observations of burrowing spiders, ants, and wasps. She reports discovering two entirely new species of spider on her acre in town, counting the numbers of burrows and regularly observing each one. She placed a number of spiders in jars, in order to study them more closely. In a rare humorous passage in the book, she explains how she kept them in captivity.

These spiders make very interesting pets. I capture them by cutting out the the nests with a sharp trowel or large knife, and have ready some glass candy jars from twelve to fourteen inches in heigh in which I carefully place them. I then fill in with earth all around, making the jar about half full, and cover the surface with moss, introducing some pretty little growing plants, so that my nervous lady friends may admire the plants without being shocked with the knowledge that each of these jars is the home of a large spider.

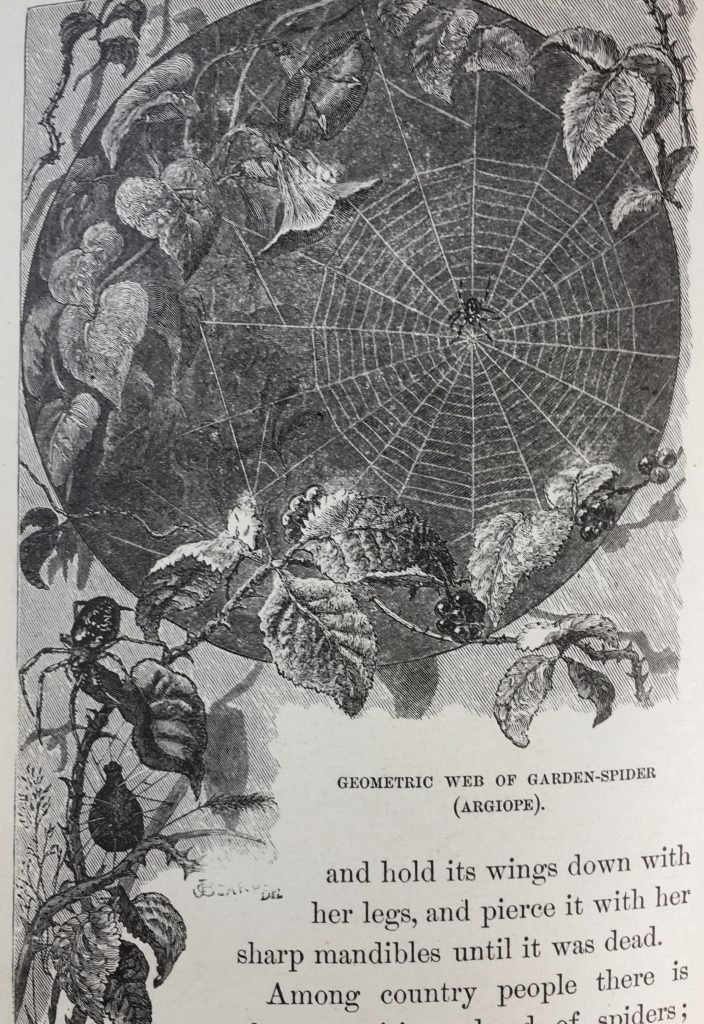

THROUGHOUT HER ACCOUNTS OF THE DAILY BEHAVIORS OF SPIDERS, WASPS, AND ANTS, SHE WRITES OF THEM WITH THOUGHTFULNESS AND RESPECT. At various points, she mentions the spiders’ “skill”, “wisdom”, and maternal “care”. “If anyone will closely observe the behavior of insects — especially ants, wasps, and spiders [evidently grouped with insects at the time] — he will not be at all startled or surprised with the announcement that these humble creatures have brains like our own.” Her writing reflects both a sense of fascination with insects and also a painstaking commitment to firsthand, rigorous study. And throughout her chapter on spiders and wasps, I encountered the most fabulous artwork, often flowing organically across much of a page, as in the case of the argiope spider web, below. (Her chapter on ants, however, was entirely devoid of illustrations.)

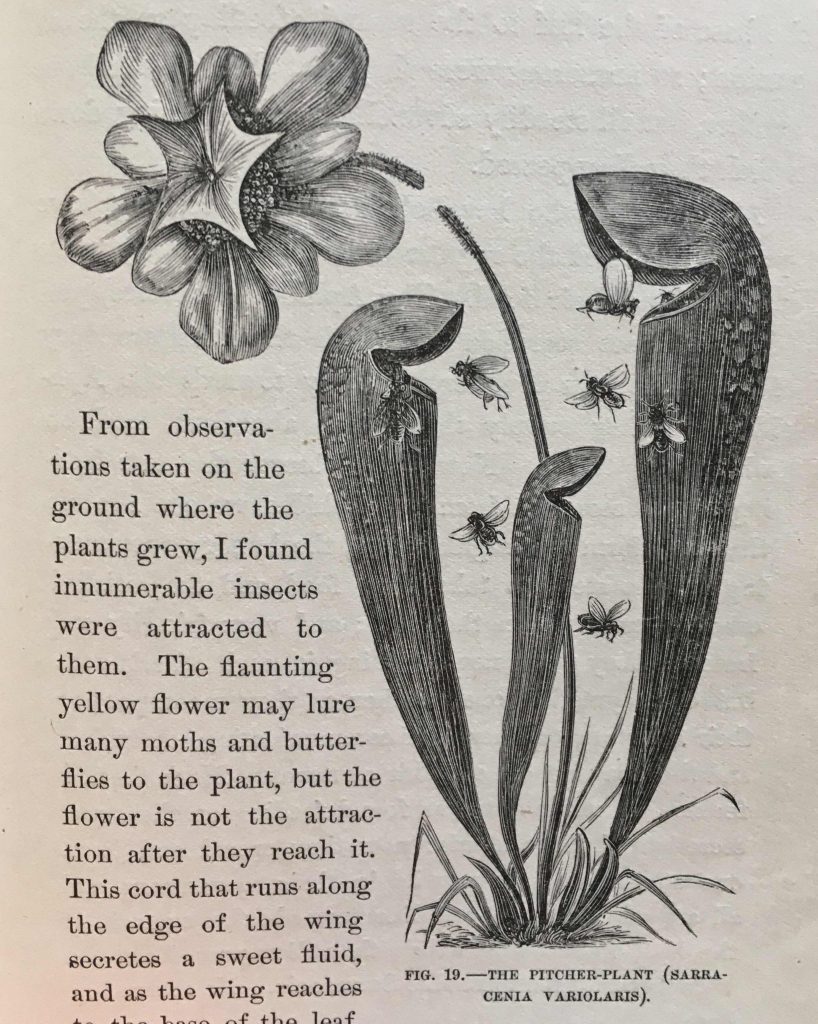

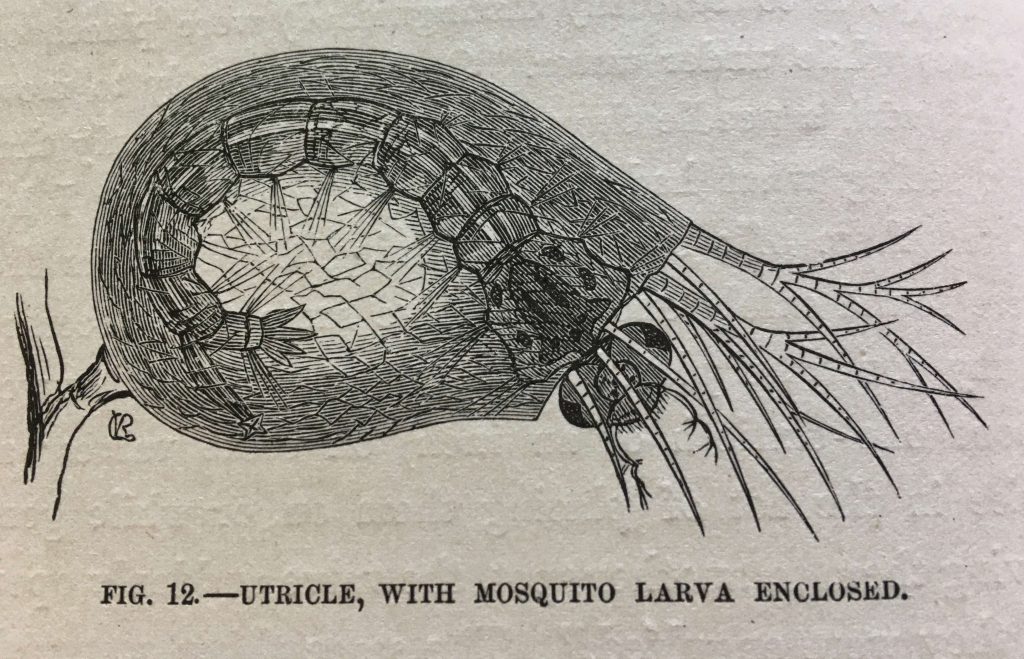

AFTER SHARING OBSERVATIONS OF BACKYARD INSECTS, THE THIRD SECTION OF TREAT’S BOOK COVERED STUDIES IN INSECTIVOROUS PLANTS. Over five chapters, she details her observations and experiments involving bladderworts, butterworts, sundews, Venus flytraps, and pitcher plants. Many of her investigations included microscopy, such as this drawing of the underwater trapping mechanism of a bladderwort, complete with its mosquito larva victim:

SHE CLEARLY SPENT MANY TEDIOUS HOURS TRYING TO FEED HER BOTANICAL CHARGES. And she documented much of it in her essays, including time of day, type of food, and response of plant. At times, her writing veered toward the kind of prose found in scientific journals; she was clearly quite comfortable in her role as scientist, making new discoveries and, even, at times, contradicting Darwin: “In a letter bearing date June 1, 1875, Mr. Darwin says: ‘I have read your article with the greatest interest…. It is pretty clear I am quite wrong….'” I wonder how often that happened. This part of the book, I confess, was tough going, and I nearly nodded off a time or two. All the plant names were in Latin (common names were only mentioned once in passing if at all), and I began wishing her observations had been reduced to a simple table or two that I might pass over. At one point (quoted at the opening of this post), Treat even recognized the somewhat painful aspect of her reporting, by offering not to “inflict” more of them on her reader.

THE LAST CHAPTER OF THE SECTION, ON PITCHER PLANTS, HOWEVER, WAS ONE OF THE MOST INTRIGUING PARTS OF THE BOOK. In it, Treat reported her observations of numerous flies and cockroaches, all of whom appeared to become intoxicated after consuming some of the liquid exuded by the pitcher plant she was studying. She described them becoming disoriented, stumbling about, and being drawn to the pitcher plant’s open mouth, “as if fascinated by some spell.” Even the ones she rescued before they were entrapped did not live very long afterwards. Treat was convinced that the pitcher plant was drugging them with some sort of toxin, though she seemed a bit frustrated that she could not provide stronger evidence for it:

I have been asked by an eminent scientist if I can prove that the flies are intoxicated. I do not see how I can prove it. I am not a chemist, and cannot analyze the secretion. I can only give the result of my observations and experiments. I might get a large quantity of the leaves and make a decoction of the secretion and drink it; but I find the flies never recover from their intoxication, and my fate might be the same if I took a sufficient quantity.

AS SCIENTISTS NOW KNOW, IT WAS A GOOD THING THAT MARY TREAT DID NOT GO FURTHER IN TRYING TO PROVE THE PITCHER PLANT WAS DRUGGING ITS PREY. We now know that at least eight species in the genus Sarracenia (to which Treat’s pitcher plants belonged) produce the alkaloid coniine, a paralyzing neurotoxin that is most commonly known as the active ingredient in poison hemlock. Consuming it in substantial quantities can cause a burning sensation in the mouth, nausea, vomiting, confusion, rapid heartbeat, seizures, paralysis, and, of course, death.

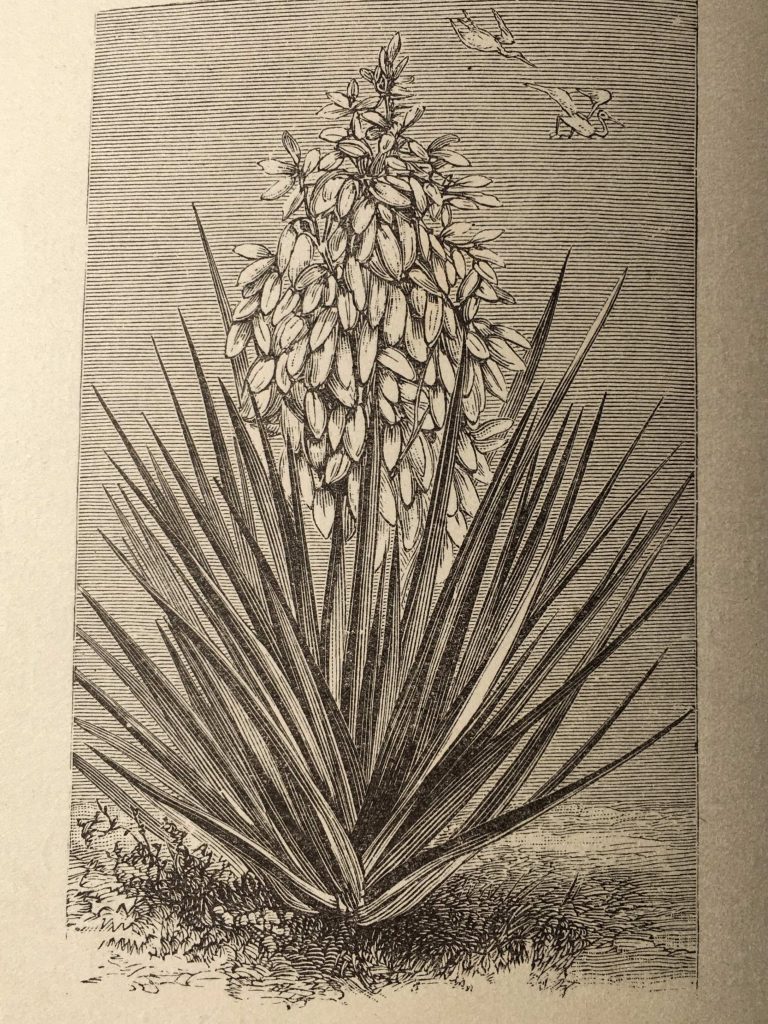

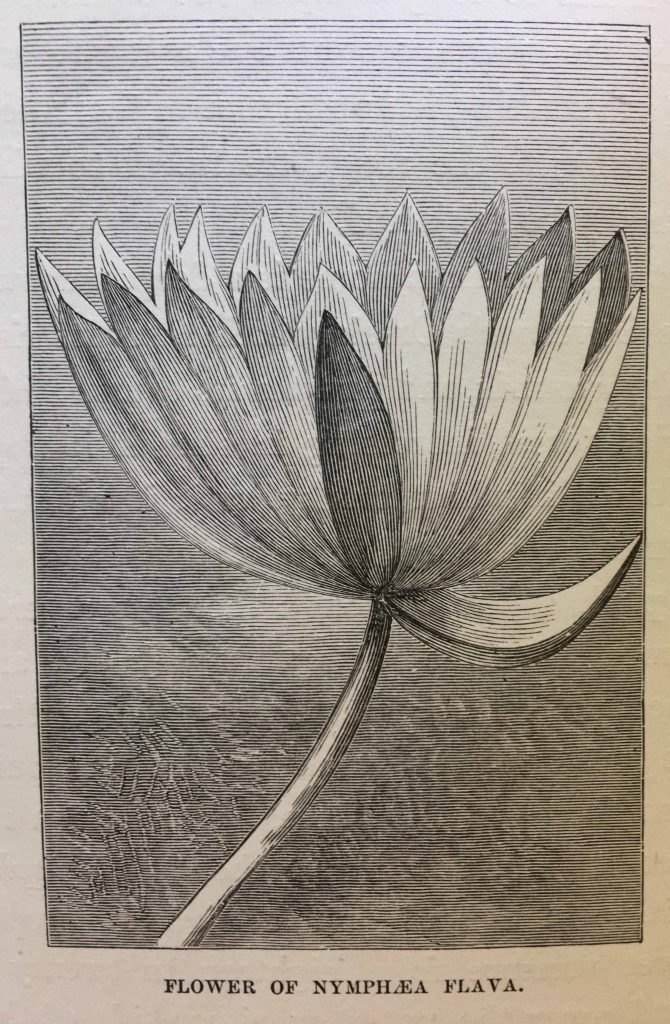

THE LAST SECTION OF THE BOOK WAS DEDICATED TO PLANTS SHE ENCOUNTERED IN FLORIDA AND NEW JERSEY. Here, her personna of experimental scientist was replaced with that of an eager, open-eyed adventurer, finding spectacular flowering plants in the nearby wilds of New Jersey and Florida. Along the St. John’s River in Florida, she found a water lily that had been depicted in a work by Audubon but never actually described, and nearby she discovered an amaryllis that was entirely new to science. She spoke highly the botanically rich landscape of northern Florida, but declared that there was no more amazing place for botanizing than the New Jersey Pine Barrens. In the only passage in the book where she writes about environmental impacts of human “progress”, she interrupts her tale of floral discoveries to note that “…within a few years past it has been found that the pine-barrens of Southern New Jersey are quite fertile, and at no distant day they are destined to become the greatest fruit gardens in the Union. And then farewell to the rare floral treasures that no art can save.” I was surprised how resigned she seemed to the inevitability of that loss. Fortunately for all of us, reports of the fertility of the Pine Barrens appear to have been greatly exaggerated; a large portion of southern New Jersey remains forested to this day.

AND SO, AFTER A FINAL PARAGRAPH EXTOLLING THE VIRTUES OF NEW JERSEY’S PINE BARRENS FLORA AND A FEW PAGES OF INDEX, THE FIRST LEG OF MY JOURNEY ENDED. I closed the book, taking a last deep draught of the volume’s delightful “old book smell” (which you can read more about here). On the whole, it was a satisfying start to my adventures. I appreciate how Mary Treat succeeded remarkably as a scientist at a time when the profession was largely closed to women. She went head to head with the likes of Darwin, and won. As a popularizer of science for the common folk, I think she was a bit less successful. “Home Studies in Nature” is at best an uneven work. It is a collection of essays, so there really isn’t any structure or theme. Its audience is sometimes the everyday reader (particularly in the section on bird nests and behavior), sometimes the fellow scientist (when reporting on experiments with spiders and pitcher plants). I get the sense from her book that she was most at home (often quite literally) when carrying out meticulous fieldwork, making amazing discoveries just beyond her doorstep or through the lens of a microscope.