…women may be imbued with a love of science for its own sake, and pursue it in spite of obstacles….

But while the road to scientific attainment is for the man broad and well-paved through centuries of use, there is generally for woman, when she dares to walk therein, a look askance and a cold reception. But she will not mind that greatly — the woman who truly loves nature….

Disappointments, discouragements, adversities constitute food for hardy natures, and no other need attempt the road of science.

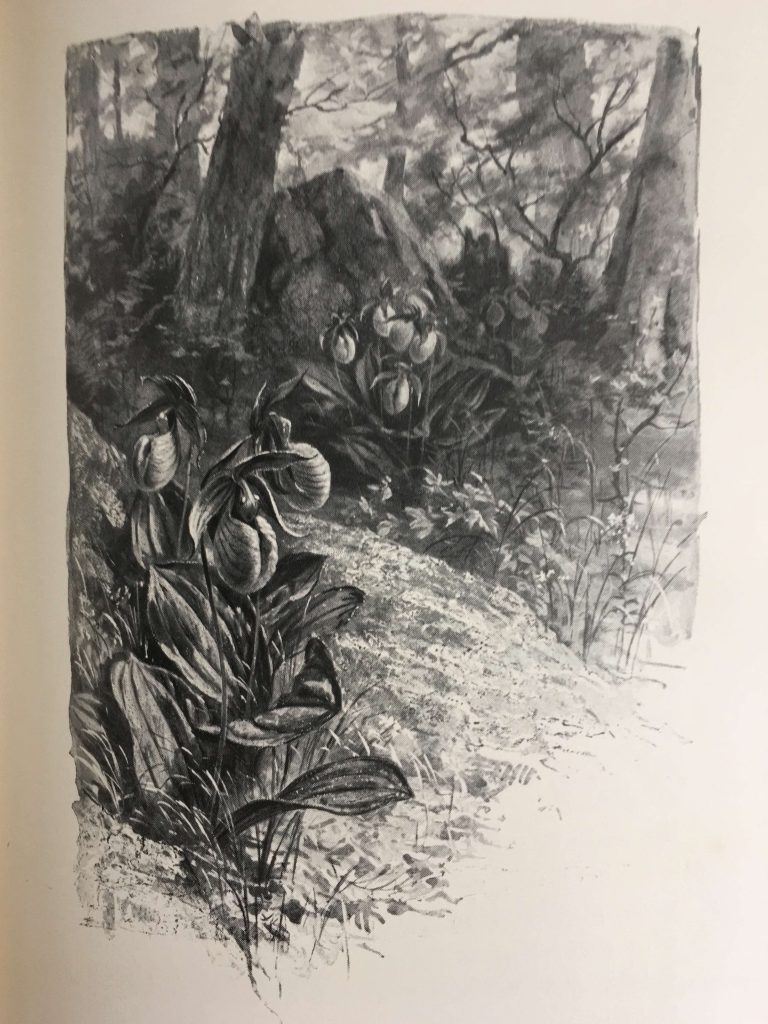

TRUE TO THE BOOK’S TITLE, “SUMMER IN A BOG” OPENS AT A BOG AT THE EDGE OF A CORNFIELD SOMEWHERE IN MADISON COUNTY, OHIO. The husband of the protagonist/author, identified as the Doctor (of Medicine), is in the process of driving past a flourishing cornfield that is interrupted by “a strip [that] seemed given over to weeds and black morass, wild grasses and moss:

“If I owned that cornfield, I’d drain it better,” said the Doctor, critically….

“It’s just like a strip of lovely flowered ribbon,” said I. “Here, stop and let me off, I’ve been intending to visit that bog for more than a year, and I’ll do it now….”

At any other time the Doctor would have found a dozen reasons why I should sit still and continue my ride, but my resolution came on so suddenly that he had not time to formulate an objection. So I was down on the road in a jiffy, trowel and portfolio in hand.

“Ribbon!” he muttered, half aloud, as he drove away….

“Crawling through a wide space in the barred fence, I found myself in a wilderness of weeds almost as high as myself. Beating these to right and left, an open spot was soon attained where the decorations of the “ribbon” came into view.

A PICTURE QUICKLY EMERGES OF A HIGHLY ENTHUSIASTIC AND EQUALLY DETERMINED WOMAN BOTANIST. PURSUING HER BLISS IN AN AGE WHEN WOMEN WERE STILL LARGELY CONFINED TO HOME LIFE. She never gives up, despite the challenges and dangers. At one point, she tells of her frightful encounter with two different tramps lying in fields; she escaped both of them without their waking up, and later found out that they were simply local workers out in the field tending to the cattle. At another point, just after the opening quote in this post and in what is perhaps the most hilarious part of the book, Sharp explains the subterfuge necessary to secure her botanical specimens:

When taking her rides abroad with unsympathetic companions, collecting, what had at first been conceded to her as a hobby of possibly brief duration, like any other fad, by reason of prolonged and persistent continuance, became burdensome; and finally, objection was not infrequently made to stopping for botanical acquisition. In this emergency, and after being summarily whisked by coveted treasures, a new expedient suggested itself.

Gloves and hand-bags had mysterious ways of falling over the wheel into the road in near proximity to new and attractive weeds: in getting out to recover the one, she audaciously insisted on securing the other. Her soul is still harrowed by recollection of a much-desired specimen, dimly identified at a moment when nothing was at hand to drop — her hat being the only article possible to so use, and it tightly, alas! pinned to her hair. What a pity that heads could not be conveniently tipped off on such interesting occasions! And that specimen has never been seen since, and is still absent from her collection.

In this passage, Sharp celebrates the delight that she finds studying collecting and identifying plants for her herbarium:

An enviable task is that of the naturalist. What pleasure nature spreads in the path of her devotee; the expectancy of the search, the unmixed joy of the discovery! There are no labors so purely delightful as those which we assume with nature.

Society, meanwhile, throws many impediments in a woman’s path to taking on that role:

What is it for a woman to be a botanist? With maternal, domestic, or social duties, to say nothing of literary, if she incline that way, and each an occupation in itself, how shall she find opportunity to cultivate acquaintance with Nature and reduce her observations to a science?

She will do it because she was born to do it; because within her is the heaven-imparted kinship with Nature which is the open sesame to that kingdom of delight. But she will do it under difficulties.

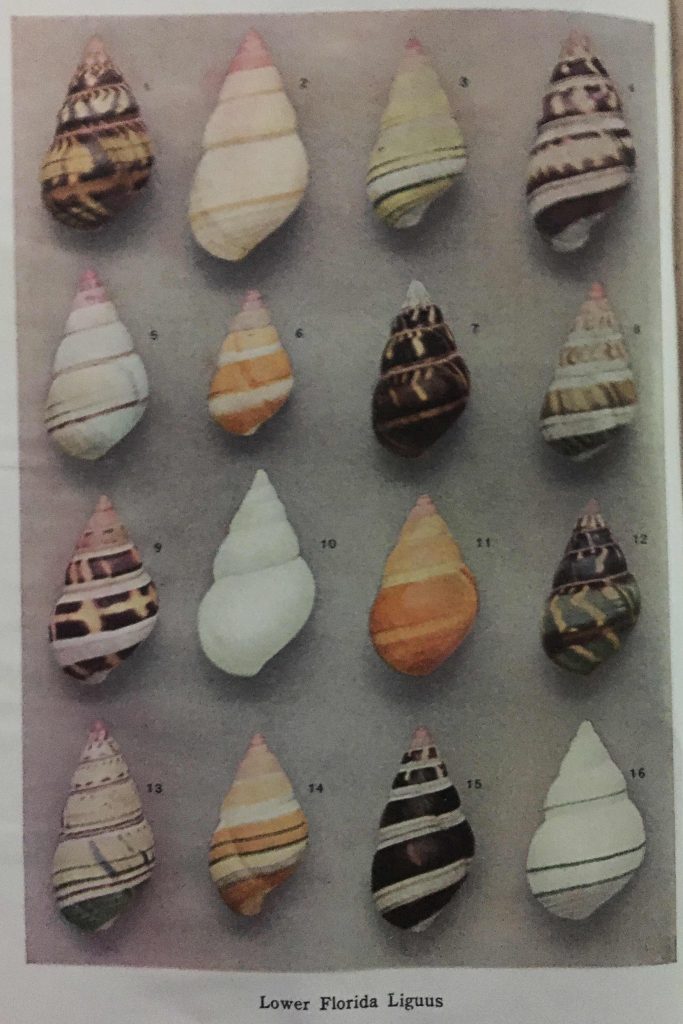

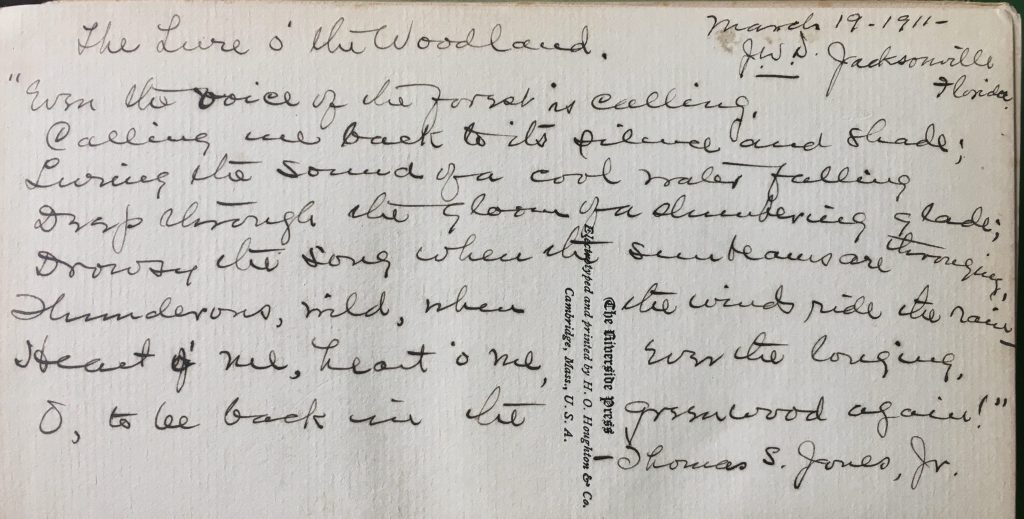

ALAS, SHARP’S BOOK IS A MISCELLANY, A COMPENDIUM OF FORMERLY PUBLISHED NEWSPAPER COLUMNS, NOT ALL OF WHICH SPEAK TO THE READER OF TODAY. Much of the opening essay, Summer in a Bog, is about the unusual human characters she encounters in the midst of her fieldwork. A later essay discusses the poisonous character of tobacco, while another essay names the women botanists in Ohio she knew or read about. The closing essay is an A to Z list, with brief biographies, of famous botanists (or persons associated with botany) around the world, from antiquity to her present day. The reader, if one pardons the inevitable pun, gets bogged down from time to time. My eyes did perk up, though, for one essay toward the end of the book: Passing of the Wildwood. First published in the periodical Plant World in May, 1900, the brief piece is a call for setting aside bits of wild nature in all communities across the country:

A glimpse of nature, an object lesson for the denizens of the city, surrounded from day to day, as they are, by the works of man; why can not such spots be spared, here and there, from the general destruction of nature’s original beauty, which takes place wherever a city is planted?

Alas, for some parts of the country in 1900, it seemed already too late:

But civilization daily encroaches upon these remnants of pristine formations, and in many localities nothing remains of nature’s original construction.

IN THE FORWARD TO HER BOOK, SHARP WONDERS TO HERSELF WHETHER IT IS REALLY WORTHWHILE TO REPUBLISH HER VARIOUS WRITINGS FROM THE COLUMNS OF PAST PERIODICALS. In order to answer that, she shares the following thoughts with her readers:

There is no ennui, no heavy time to kill, when all around us secrets of Nature invite to revealment. Then, secrets no longer, let us while away a little time in recording them.

So, if anything is learned from these pages, if any impulse in the right direction proceeds from them, or if they furnish only the entertainment of an idle hour, they are worth while.”

THANK YOU, KATHERINE DOORIS SHARP, FOR A WORTHWHILE READ.

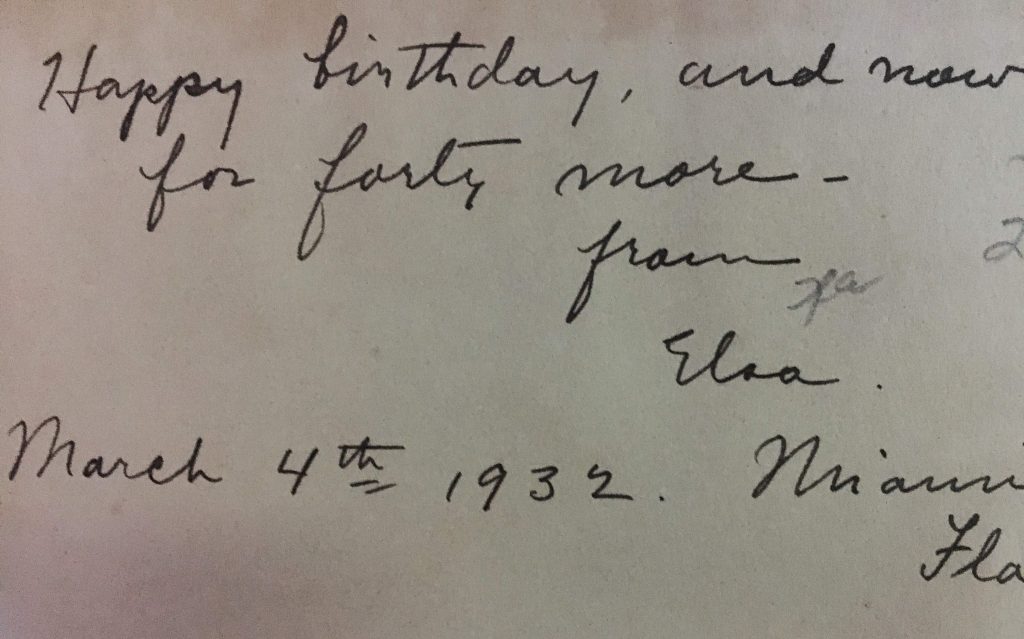

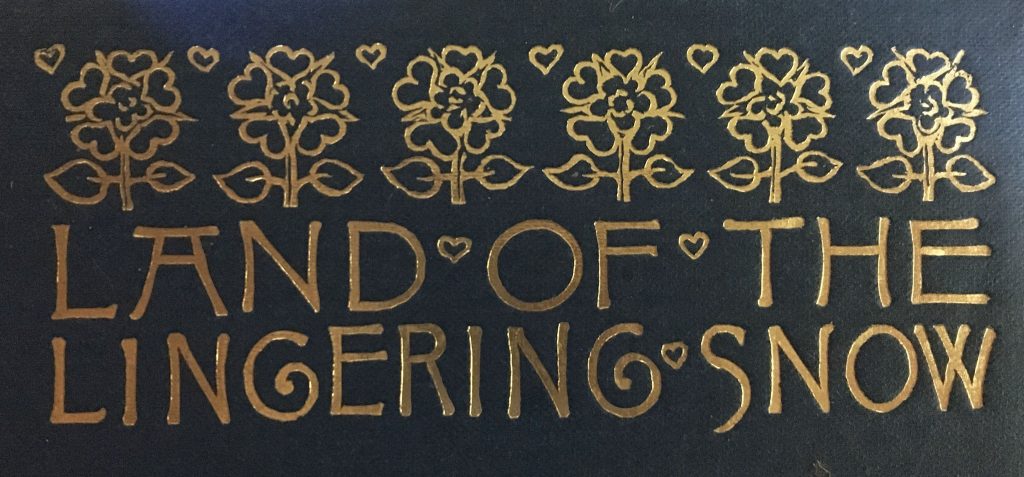

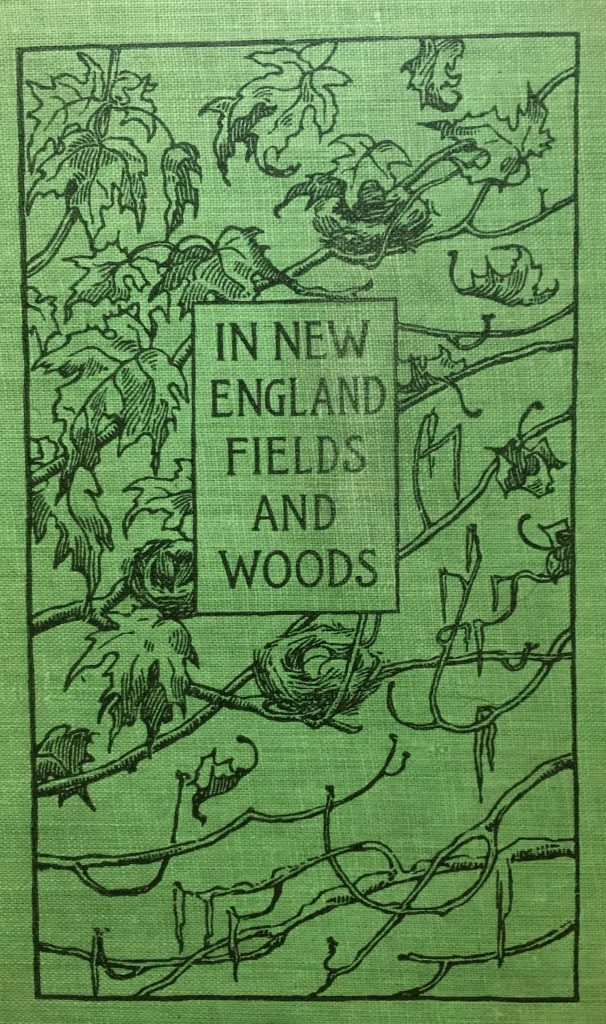

FINALLY, A WORD ABOUT MY COPY OF THIS BOOK. Yet again, a first edition was well outside my price range, and I suspect there was no second edition printed. Fortunately, thanks to Forgotten Books, a publisher that re-prints scanned copies of books no longer under copyright, I was able to secure a like-new paperback copy for a pittance. I miss the sense of history, though I still prefer it to the Kindle alternative (even though it is a far better choice from an environmental viewpoint).