I have read over fifty nature books for this blog thus far, with every expectation of at least that number before this project’s close (or, at least, transition into possible presentations and even a book — stay tuned!). I have gotten this far without once feeling befuddled about how to describe and interpret a book. This time, though, I have had to look to outside guidance, in the form of the words of Christopher Morley. He published a collection of Modern Essays in 121, including a chapter from this book in his anthology. He prefaced it with the following:

Marion Storm was born in Stormville, N.Y., and educated at Penn Hall, Chambersburg, Pa., and at Smith College. She did editorial and free-lance work in New York after graduation, and later went to Washington to become private secretary to the Argentine Ambassador. Since 1918 she has been connected with the New York Evening Post.

This essay comes from Minstrel Weather, a series of open-air vignettes which circle the zodiac with the attentive eye of a naturalist and the enchanted ardor of the poet.

Here I recall other nature writers I have read, who defined the art of a nature essay as combining science and poetry. For most authors thus far, the two have been fairly distinguishable: a few paragraphs of description interspersed with a few lines of poetry. But here, the two are fused together, and the reader is left with a whirlwind of carefully crafted images, spinning, flowing, changing from one into another, following the progression of the seasons back to the beginning. Consider this passage, from “Hay Harvest Time”, for June:

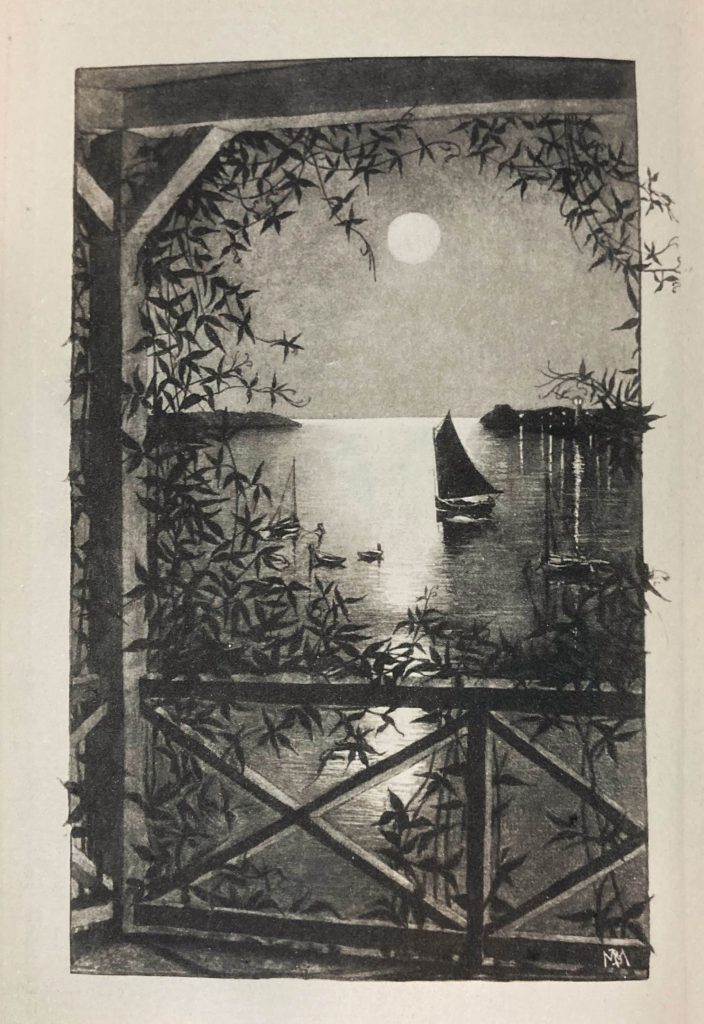

Into the whispering twilight of June come many creatures to play strange games and sing such songs as even the many-stringed orchestra of the sunlit hayfield does not know. The swooping bat darts from thick-hung woodbine and noiselessly crosses the garden, brushes the hollyhocks, and speeds toward the moon. Moths, white and pallid green, wander like spirits among the peonies. Sometimes the humming bird shakes the trumpet vine in the dark, queerly restless, though he is Apollo’s acolyte. The fireflies are lambently awing. The cricket’s pleading, interrupted song is half silenced by the steady, hot throb of the locust’s. The tree toad’s eerie note comes faint and sweet, but from what cranny of the bark only he knows. The mother bird, guardian even in sleep, speaks drowsily to her children. From the brooding timber the owl sends his call of despair across acres of friendly fields placid in the dew. Then enchantment deepens, fr there comes o pause in darkness for the joy of earth.

And there is no pause to the flow of events — each one a single jewel on a bracelet or bead on a rosary. Each sentence conjures another facet of nature’s magnificent abundance. The result is almost overwhelming. Through it all, Storm demonstrates a keen awareness of nature (particularly plants) blended with a bit of fancy — a “touch of fairie”. I could pick up the book at random and quote another passage of wonder, delight, and even a touch of humor. For instance, consider this listing of apple varieties (now mostly lost):

Down in the valley, through the woodsmoke haze. move the slow apple wagons through the lanes. This is appleland. Northern Spy and Lemon Pippin are ripe to cracking; Baldwins will be mellow by Twelfth-Night, the russet at Easter. Gorgeous and ephemeral hangs the Maiden’s Blush. The strawbery apples are like embers on the little trees, rubies of the orchard. Lady Sweets and Dominies are respectfully being urged into the cellar, and for those who will pay to learn the falseness of this world’s shows the freight cars are receiving Ben Davises. Sheep-noses, left often on the boughs, will hold cold nectar after the black frosts have killed the last marigold. They lie, dull red, by the orchard fence in the early snow, their blunt expression revealing no secrets. You have to know about them. Nothing is more inscrutable than a sheep-nose.

For the most part, her scenes are bucolic, the human participants mostly country folk who appear to be largely in harmony with nature. Norman Rockwell would be at home in Storm’s domain. Only once late in the book (after the year’s round is done), in “The Play of Leaves,” does Storm speak somewhat ill of humanity. In this case, her complaint is in regard to exotic (perhaps even invasive) species (fungal blights and the like) and their ecological impacts:

[Little leaves] are as playful as kittens, with their dances, poses, flutters, their delicate bursts of glee. Unless involved with flowers, or with timber or real estate, they are safe, not alone in winer babyhood, but throughout spring and summer, that minister to them with baths of dew and rain and with the somnolent wine of the sun. Only when old age has brought weariness and winds and heat, and even with the drawing of the sap, are they confronted by their enemy, frost. You will say, caterpillars, forest fires, but they are the fault of man and an unanticipated flaw in nature’s plan for letting the leaves off easily. We brought foreign trees that had their own mysterious protection at home into lands where that immunity vanished, and so the chestnut has left us, and apple and rose are threatened by foes whom their mother had not forseen. Were it not for man’s mistakes the leaves would have had an outrageously gay time with comparison to the darkling lives of the creatures that move among them and beneath them.

Even here, the suggestion is that we make “mistakes”, not that we are willfully destructive to the environment.

Minstrel Weather was Marion Storm’s first book. It would be another eleven years before she would publish again. By then, she had moved to Mexico, where she would write several additional books on Mexican culture and natural history. She would never return to the US, passing away in Guadalajara in 1975. Her obituary mentioned several of her books set in Mexico, but not this one.

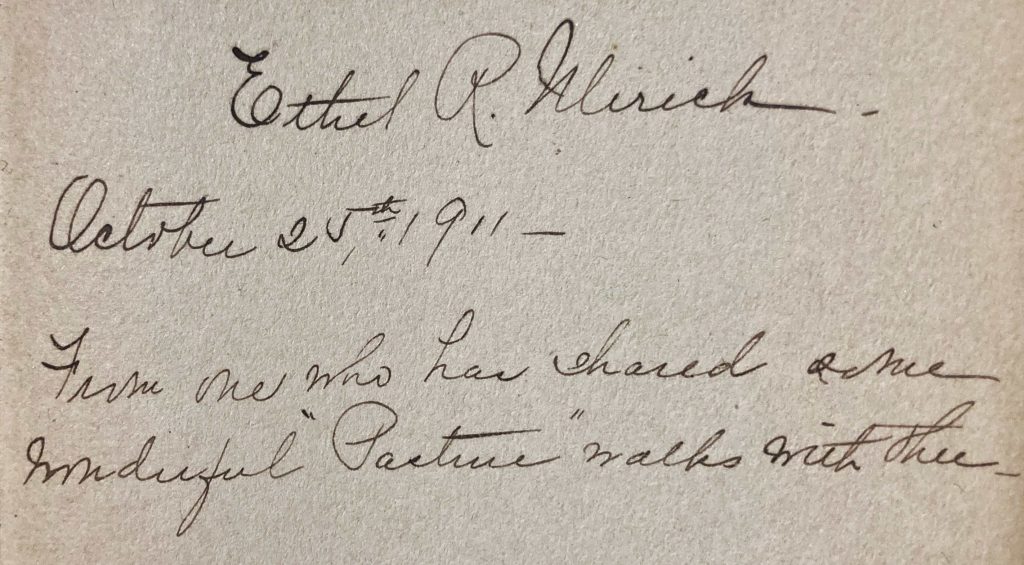

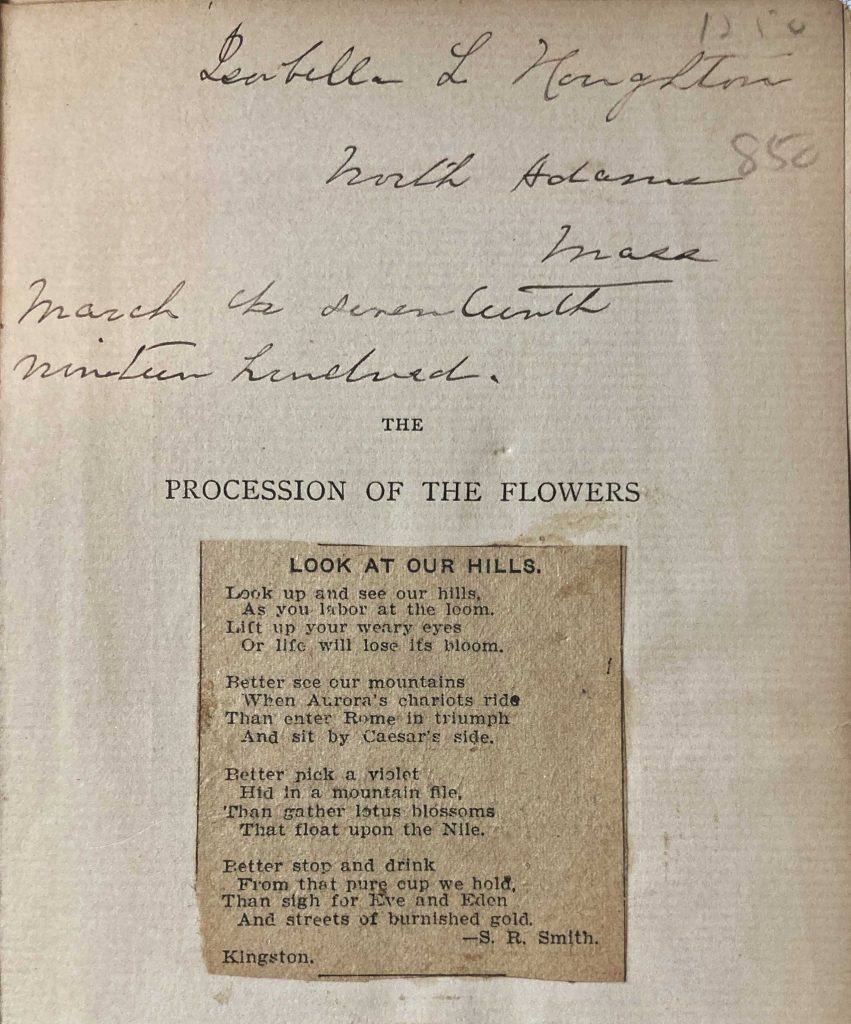

As for my copy, a tiny book stamp in the back indicates that it was sold at the Neighborhood Book Shop, 435 Park Avenue [New York]. Someone must have purchased the book and taken it home. But given the numerous uncut pages, it is clear that I was the first to read it cover to cover.