When, at any time in our earthly life, we come to a moment or place of tremendous interest it often happens that we realize the full significance only after it is all over. In the present instance the opposite was true and this very fact makes any vivid record of feelings and emotions a very difficult thing. At the very deepest point we reached I deliberately took stock of the interior of the bathysphere; I was curled up in a ball on the cold, damp steel, Barton’s voice relayed my observations and assurances of our safety, a fan swished back and forth through the air and the ticking of my wrist-watch came as a strange sound of another world.

Soon after this there came a moment which stands out clearly, unpunctuated by any word of ours, with no fish or other creature visible outside. I sat crouched with mouth and nose wrapped in a handkerchief, and my forehead pressed close to the cold glass—that transparent bit of old earth which so sturdily held back nine tons of water from my face. There came to me at that instant a tremendous wave of emotion, a real appreciation of what was momentarily almost superhuman, cosmic, of the whole situation; our barge slowly rolling high overhead in the blazing sunlight, like the merest chip in the midst of ocean, the long cobweb of cable leading down through the spectrum to our lonely sphere, where, sealed tight, two conscious human beings sat and peered into the abyssal darkness as we dangled in mid-water, isolated as a lost planet in outermost space. Here, under a pressure which, if loosened, in a fraction of a second would make amorphous tissue of our bodies, breathing our own homemade atmosphere, sending a few comforting words chasing up and down a string of hose—here I was privileged to peer out and actually see the creatures which had evolved in the blackness of a blue midnight which, since the ocean was born, had known no following day; here I was privileged to sit and try to crystallize what I observed through inadequate eyes and interpret with a mind wholly unequal to the task. To the ever-recurring question, “How did it feel?”’, etc., I can only quote the words of Herbert Spencer, I felt like “an infinitesimal atom floating in illimitable space.” No wonder my sole written contribution to science and literature at the time was “Am writing at a depth of a quarter of a mile. A luminous fish is outside the window.”

The C. William Beebe who traveled to Mexico in 1904 was definitely not the same Beebe who recorded the bathysphere’s deep ocean expeditions off the coast of Bermuda three decades later. The prose is far less rambling, and the book’s structure almost too consciously engineered: opposite the table of contents is an outline of the divisions of the book: Emotional (Chapter 1); Historical (Chapters 2-3), Pragmatic (Chapters 4-9), and Technical (Appendices). After an opening I would classify more as philosophical than emotional, the book devotes four chapters to the history of deep ocean exploration, culminating with Otis Barton’s design of the bathysphere. In a volume of only 225 pages (excluding the appendices), the first underwater visit to “Davy Jones’s Locker” doesn’t get underway until a hundred pages in. When it does, the more wooden prose of Beebe’s historical narrative gives way to passages expressing the childlike wonder he found in encountering new worlds. Until Beebe’s journeys, no one had ventured a quarter mile beneath the sea, let alone half a mile. The water pressures at such depths would kill a diver instantly. And deepwater trawls yielded only bits of dead fish; their bodies, so well adapted to the insane pressure of the deep ocean, could not endure when brought up to the surface. As the bathysphere passed below the range of light penetration, it very much entered an entirely new world.

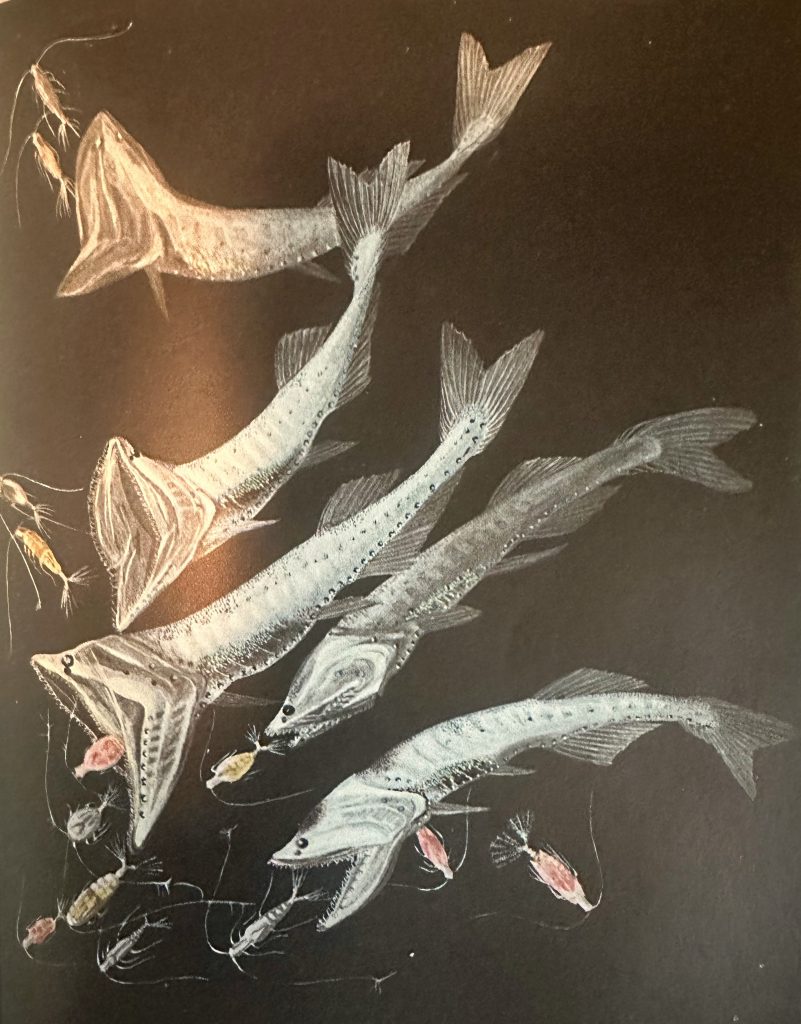

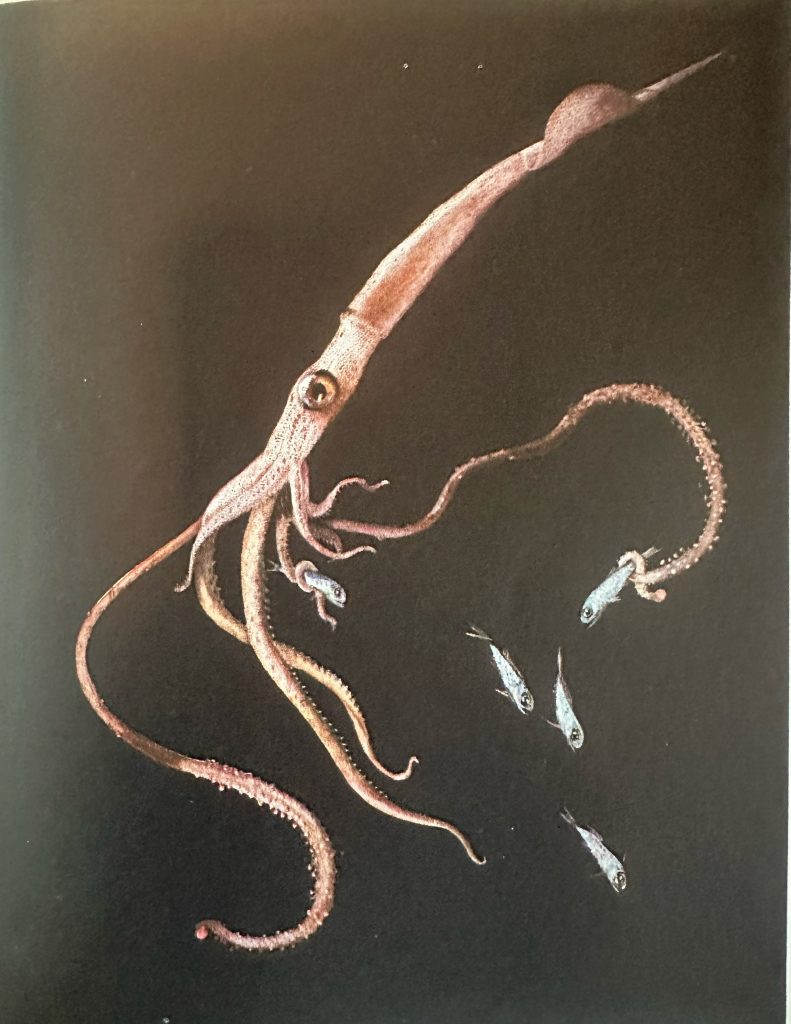

On all but one of the dives — Beebe allowed two assistants to go down a short distance below the waves in celebration of a birthday) — the bathysphere was manned by William Beebe and Otis Barton. Barton, as the designer of the bathysphere and the chief funder of the expedition, allowed its use provided he accompanied Beebe on the dives. History has not been kind to Barton; in The Bathysphere Book, Brad Fox depicts him as entirely ineffectual at taking underwater photographs (though he kept on trying), less than useful at observing and describing marine life, and prone to bouts of nausea while sealed inside a tiny metal ball with Beebe. In the absence of photographs, the most stunning expedition discoveries were instead immortalized in paintings by Else Bostelmann. Like a forensic artist creating a composite image of a suspect from witness accounts, Else worked closely with Beebe to translate his word descriptions into stunning visual images. Tragically, an online scan of the book at Archive.org is missing the color paintings; they may not have been included in all editions of the book.

Today, of course, the modern reader with an interest in the deep ocean will have seen abundant photos and videos of many of the fishes Beebe saw, along with even stranger ones as much as seven miles down (plus, in a quite unsettling discovery, a plastic bag). In our day of access to visuals of all types (real and AI-generated) on the Internet, along with quite a few years of VR technology, it is difficult to imagine the degree of wonder Beebe experienced half a mile below the sea surface, suspended in a tiny metal ball, gazing out into an inky blackness occasionally aluminated by a light he turned off and on at intervals. Indeed, the finest moments in the text, in my opinion, are Beebe’s thoughts about the nature of the experience — his amazement and awe at the oceans’ vastness in space and time.

While still near the lowest limit of our dive the thought flashed across my mind of the reality of the old idea of elements—fire, water, earth, and air. They persist as a mental concept, no matter how our physicists and chemists continue to discover new elements, to dismember atoms, and to recognize such invisible phenomena as neutrons. I have seen and felt the heat of molten, blazing stone gushing out of the heart of our Earth; I have climbed three and a half miles up the Himalayas and floated in a plane still higher in the air, but nowhere have I felt so completely isolated as in this bathysphere, in the blackness of ocean’s depths. I realized the unchanging age of my surroundings; we seemed like unborn embryos with unnumbered geological epochs to come before we should emerge to play our little parts in the unimportant shifts and changes of a few moments in human history. Man’s recent period of strutting upon the surface of the earth would have to be multiplied half a million times to equal the duration of existence of this old ocean.

This is not to rule out, of course, the scientific discoveries Beebe made, including the identification of several new fish species. In this passage, he shares a literal flash of inspiration that resolves a long-standing puzzle from earlier dives of sudden flashes of light he would notice through the bathysphere’s window in the blackness of the deep sea’s “perpetual night”:

I have spoken of the three outstanding moments in the mind of a bathysphere diver, the first flash of animal light, the level of eternal darkness, and the discovery and description of a new species of fish. There is a fourth, lacking definite level or anticipation, a roving moment which might very possibly occur near the surface or at the greatest depth, or even as one lies awake, days after the dive, thinking over and reliving it. It is, to my mind, the most important of all, far more so than the discovery of new species. It is the explanation of some mysterious occurrence, of the display of some inexplicable habit which has taken place before our eyes, but which, like a sublimated trick of some master fakir, evades understanding.

This came to me on this last deep dive at 1680 feet, and it explained much that had been a complete puzzle. I saw some creature, several inches long, dart toward the window, turn sideways and—explode. This time my eyes were focused and my mind ready, and at the flash, which was so strong that it illumined my face and the inner sill of the window, I saw the great red shrimp and the outpouring fluid of flame. This was a real Fourth Moment, for many “dim gray fish” as I had reported them, now resolved into distant clouds of light, and all the previous “explosions” against the glass became intelligible. At the next occurrence the shrimp showed plainly before and during the phenomenon, illustrating the value in observation of knowing what to look for. The fact that a number of the deep-sea shrimps had this power of defense is well known, and I have had an aquarium aglow with the emanation. It is the abyssal complement of the sepia smoke screen of a squid at the surface.

Here, a bit abruptly perhaps, my blog post ends. For Beebe, too, when the expedition concluded, so did his days of deep underwater study. Ultimately, he would return to land, particularly the tropical jungles that he loved. The year Half Mile Down was published, Otis Barton would Otis Barton set a new human diving record, reaching 1,370 meters down (0.85 miles) in the bathysphere. And then, in 1960, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh would descend to the bottom of the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench (10,740 meters or 6.67 miles down). Seventeen years later, the bizarre chemosynthesis-based ecosystem of the hydrothermal vents would be encountered for the first time.