Because I was newly in the country I was constantly under the feeling of its past. Hither and thither I went in the region round about, listening at every turn, spying into every bush at the stirring of a leaf or the chirp of a bird; yet I had always with me the men of ’63, and felt always that I was on holy ground.

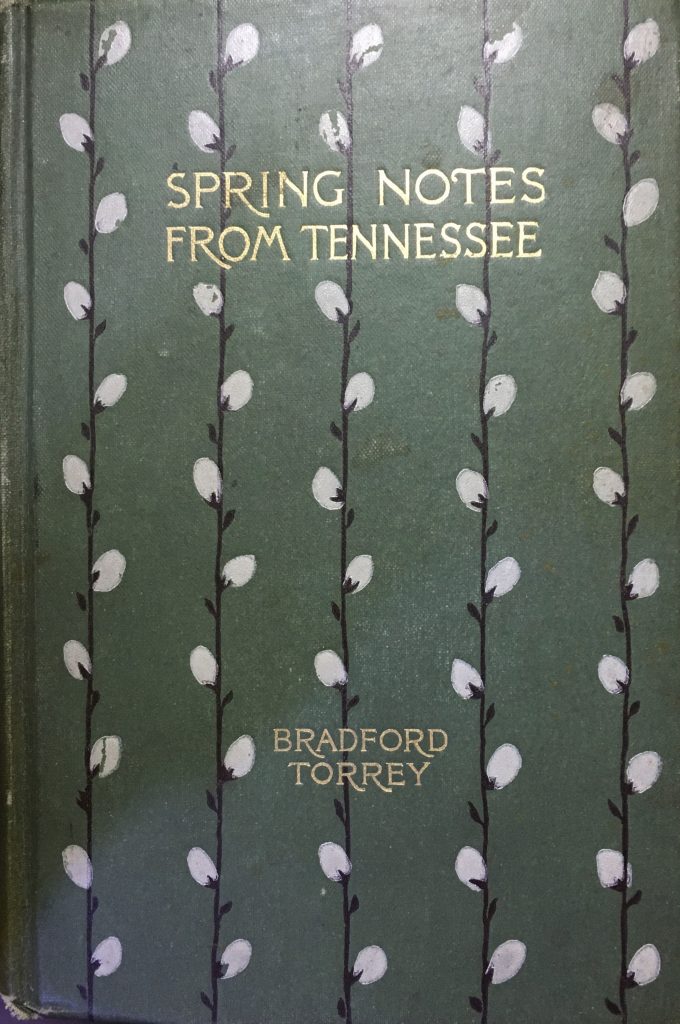

IN 1895 OR THEREABOUTS, THE BOSTON NATURE WRITER BRADFORD TORREY VACATIONED FOR SEVERAL WEEKS IN SOUTH-CENTRAL TENNESSEE. An avid birder and occasional appreciator of other animals or native plants, he spent most of his time roaming a Civil Warm landscape in search of birds. In that quest he is, at times, quite intense. The story opens with his arrival at Missionary Ridge, outside Chattanooga. The rail car he has taken was occupied by several Confederate veterans who invite him to join them in climbing a view tower at the site of General Braxton Bragg’s headquarters “where they would show me the whole battlefield and tell me about the fight.” Instead, distracted by a bird, Torrey remains on the ground. “I might have heard all about the battle from a man who was there,” he relates to his readers, “and instead I went off to listen to a sparrow singing in a bush.” And for the next several dozen pages, all Torrey writes about are the birds he encounters — the ones he sees and identifies, and the ones he only hears and wonders about. Meanwhile, in the background is the immense drama that unfolded there about thirty years before, including the Battle of Chickamauga, a Confederate victory that was not enough to turn the tide of war in the Rebels’ favor. In the 1890s, many Civil War veterans were still living, and would visit the battlefields to recall their past moments of glory and struggle. Residents of the area, too, carried memories of those fateful days in September of 1863.

Finally, the Civil War seeps into Torrey’s tale, displacing the endless litany of birds. While on Chickamauga battlefield, the author converses with a Confederate veteran of Vicksburg:

…he gave me a vivid description of his work in the trenches, as well as the surrender, and the happiness of the half-starved defenders of [Vicksburg], who were at once fed by their captors.

All his talk showed a lively sense of the horrors of war. He had seen enough of fighting, he confessed; but he could n’t keep away from a battlefield, if he came anywhere near one.

All around him, the landscape contained traces of its violent past, brought back to life by first-hand and second-hand memories of those terrible days of war:

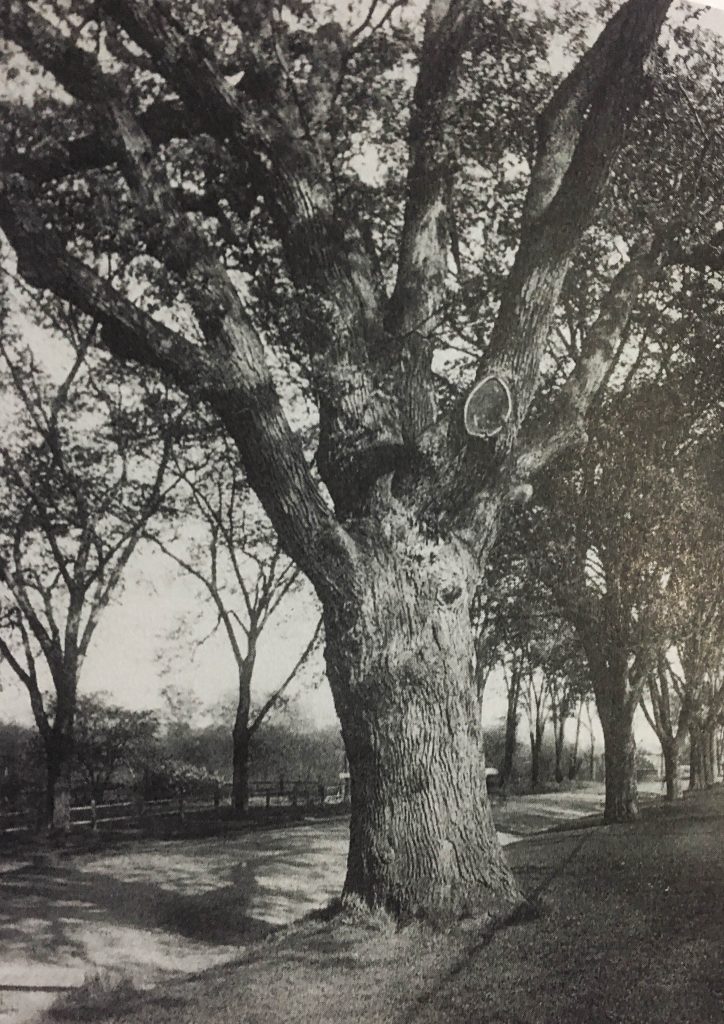

From the hill it was but a few steps to the Snodgrass house, where a woman stood in the yard with a young girl, and answered all my inquiries with cheerful and easy politeness. None of the Snodgrass family now occupied the house, she said, though one of the daughters still lived just outside the reservation. The woman had heard her describe the terrible scenes on the days of the battle. The operating-table stood under this tree, and just there was a trench into which the amputated limbs were thrown. Yonder field, now grassy, was then planted with corn; and when the Federal troops were driven through it, they trod upon their own wounded, who begged piteously for water and assistance. A large tree in front of the house was famous, the woman said; and certainly it was well hacked. A picture of it had been in “The Century.” General Thomas was said to have rested under it; but an officer who had been there not long before to set up a granite monument near the gate told her that General Thomas did n’t rest under that tree, nor anywhere else. Two things he did, past all dispute: he saved the Federal army from destruction and made the Snodgrass farmhouse an American shrine.

After passing the home that had been General Rosencrans’ headquarters during the battle, Torrey relates to readers,

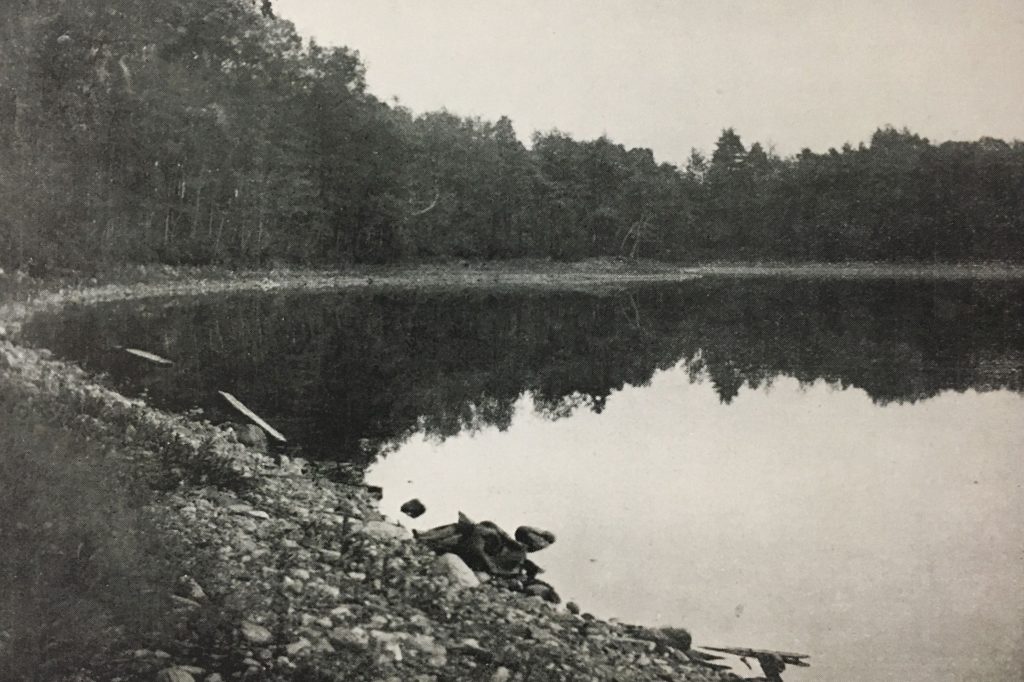

…I came to a diminutive body of water, — a sink-hole, — which I knew at once could be nothing but Bloody Pond. At the time of the fight it contained the only water to be had for a long distance,. It was fiercely contended for, therefore, and men and horses drank from it greedily, while other men and horses lay dead in it, having dropped while drinking….

…a chickadee gave out his long and quiet sound just behind me, and a…swallow dropped upon the water’s edge. The pond was of the smallest and meanest, — muddy shore, muddy bottom, and muddy water; but men fought and died for it in those awful September days of heat and dust and thirst. There was no better place on the field, perhaps, in which to realize the horrors of the battle, and I was glad to have the chickadee’s voice the last sound in my ears as I turned away.

Throughout much of his stay in that part of Tennessee, Torrey kept encountering veteran soldiers and older civilians who recalled events from the Civil War. At one point, he met up with an old Union soldier from Massachusetts who had been born in Canada but joined up with a Michigan regiment. Torrey explained to readers that he wasn’t certain how it came to pass that he learned this information, but “in that country, where so much history had been made, it was hard to keep the past out of one’s conversation.”

ULTIMATELY, THOUGH, IT WAS THE PROSPECT OF BIRDING THAT BROUGHT TORREY TO TENNESSEE, AND THE BOOK IS MOSTLY ABOUT THAT. I am sure there are avid birders out there that relish accounts of other’s efforts to augment their life lists, but I do not count myself among the number. After telling of his unexpected glimpse of a Cape May warbler on Cameron Hill in Chattanooga, Torrey explained why he kept searching for birds — an argument that ultimately led him to speak in defense of all naturalists and the lives they lead:

“What good does it do?” a prudent friend and advisor used to say to me, smiling at the fervor of my first ornithological enthusiasm. He thought he was asking me a poser; but I answered gaily, “It makes me happy;” and taking things as they run, happiness is a pretty substantial “good.” So was it now with the sight of this long-desired warbler. It taught me nothing; it put nothing into my pocket, but it made me happy, — happy enough to sing and shout , though I am ashamed to say I did neither….

It is one precious advantage of natural history studies that they afford endless opportunities for a man to enjoy himself in this sweetly childish spirit, while at the same time his occupation is dignified by a certain scientific atmosphere and relationship. He is a collector of insects, let us say. Whether he goes to the Adirondacks for the summer, or to Florida for the winter, he is surrounded with nets and cyanide bottles. He travels with them as another travels with packs of cards. Every day’s catch is part of the game; and once in a while, as happened to me on Cameron Hill, he gets a “great hand,” and in imagination, at least, sweeps the board. Commonplace people smile at him, no doubt; but that is only amusing, and he smiles in turn. He can tell many good stories under that head. He delights to be called a “crank.” It is all because of people’s ignorance. They have no idea that he is Mr. So-and-So, the entomologist; that he is in correspondence with learned men the country over; that he once discovered a new cockroach, and has had a grasshopper named after him; that he has written a book, or is going to write one. Happy man! a contributor to the world’s knowledge, but a pleasure-seeker; a little of the savant, and very much of a child; a favorite of Heaven, whose work is play. No wonder it is commonly said that natural historians are a cheerful set.

Now there’s a sentiment that George Torrey Simpson (no relation) would have agreed to with enthusiasm!

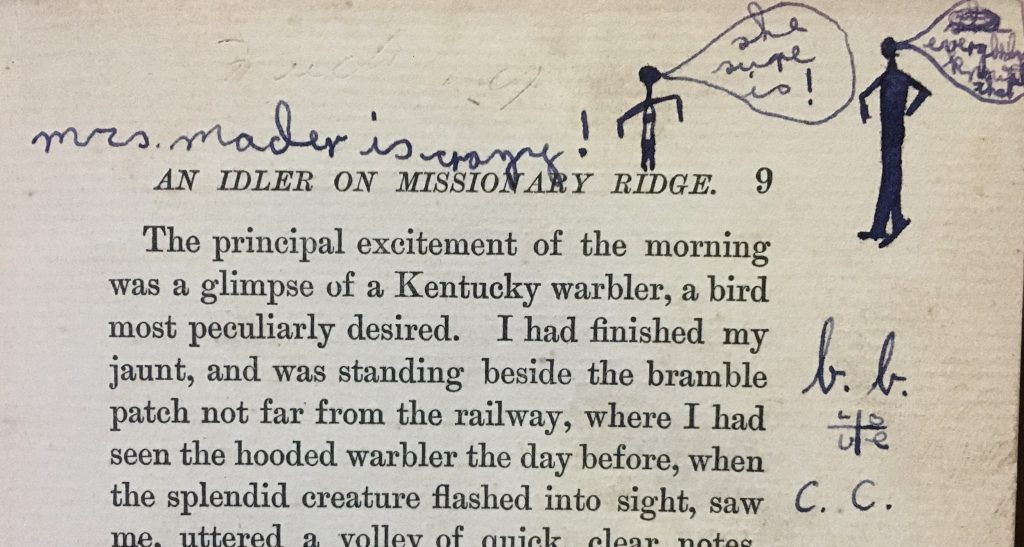

FINALLY, A FEW WORDS ABOUT MY BOOK. A “first edition” (was there a second?) from 1896, its cover (show at the opening of this post) is its finest feature. Inside the front cover is the signed name of a previous owner, who was evidently the mother-in-law of the person who sold me the book on eBay: Marguerite Heloise Crownover. The other feature of this volume is a child’s cartoon on page 9, preserving for posterity the claim that “mrs. mader is crazy!” In some truly enlightened dialogue, the smaller stick figure says “she sure is!” while the taller ones, arms akimbo, declares that “everybody knows that”. It was news to me, at least. Below the drawing is a mysterious bit of writing involving b. b. and c. c. with a plus and the letters l, o, v, and e in the four quadrants. The identities of the two besotted youths have, alas, been lost to history.

The obvious question, then, is was this actually a classroom literature text? If so, I would have to agree with the artist that Mrs. Mader was indeed crazy.