“To the lover, especially of birds, insects, and plants, the smallest area around a well-chosen home will furnish sufficient material to satisfy all thirst of knowledge through the longest life.”

I HAVE DECIDED TO EMBARK ON A JOURNEY. It is not a journey marked by miles — in light of the recent pandemic, I have only been away from my home twice since mid-March, both times venturing only as far as our CSA Farm in Fairburn, less than ten miles from doorstep. It is, instead, a journey into the past (and as I write this, I hear faint strains of Jethro Tull, Living in the Past). Like Ian Anderson, I seek solace and shelter from an unsettling world, one that presses itself into my office and into my being practically every hour of every day. This journey is one into a Golden Age — not a utopia, certainly, but a time of promise and possibility — a time when nature writing in America blossomed, for lack of a better word. Will you join me on my travels? I have mapped out a path in books lined neatly along the upper shelf of my bookcase. Adventures await!

I HAVE GONE ON AN AMAZING JOURNEY BEFORE. It is chronicled already in this blog. Half a dozen years ago, I set out down Piney Woods Church Road, an unassuming byway a short distance from my front door. I walked over 350 miles on that trip. For one year, every day, I walked that patch of road, between my home street of Rico Road at one end and Hutcheson Ferry Road, a bustling path from the outside world to Serenbe, at the other. Every day, I carried my camera, and found new things to photograph and appreciate. I have been overseas many times now — Australia, New Zealand, Bolivia, Ireland, Belize, Malta — but the journey I am most enamored of, the one that taught me the most, is the one I took on foot, here in Georgia, along the same pathway of gravel and dust, past the front and back yards of neighbors, along fields of cattle and horses.

AT LONG LAST, IT IS TIME TO WANDER AGAIN. After my last travels, I fully expected to keep wandering. I envisioned myself a Dirt Road Pilgrim, walking the backroads of Chattahoochee Hills, taking more photographs and having more adventures. Somehow, that never happened. There was something magical, I think, about the level of commitment I had to make in order to take my first journey. Every day, for an entire year, I remained at home, faithfully recording the quotidian wonders of a space that was practically my backyard. And the thought of shifting to once a week, or even once a month, just didn’t seem the same. Oddly enough, it felt like more of an obligation than a calling. Instead, I waited. And now the waiting is finally over. My path has appeared — not one that begins at my front walk or even in the trace of a colored line on Google Maps, but in an ever-growing row of dusty, somewhat tattered volumes on a shelf.

IN THESE TROUBLED TIMES, I SET FORTH IN SEARCH OF HEALING. I seek to assuage the sufferings of myself and my world, to find moments of comfort and calm, maybe even to encounter flashes of wonder and hope. And I believe — I know — they can be found between the covers of aged, largely-forgotten texts. My quest will lead me back and forth across a span of one hundred years, between about 1840 and 1940, and into books whose titles I had until recently never heard of, by authors I had scarcely imagined even existed. Yes, there will be the occasional visit with an old friend — Henry Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Burroughs, John Muir. But mostly I will be seeking the acquaintances of a lesser-known assortment of nature writers — some even contemporaries of Thoreau and Burroughs, most commemorated only in my Biographical Encyclopedia of Early American Nature Writers (edited by Daniel Patterson) and/or a brief entry in Wikipedia. Many of them are women. All of them have wonders aplenty to share. Will you join me?

FOR THIS JOURNEY, LIKE MY EARLIER ONE, I HAVE SET MYSELF A COUPLE OF RULES TO FOLLOW. I have committed myself, wherever possible, to reading original copies of each writer’s work. I believe that the magic of a book does not end with the words themselves. Ancient volumes, imbued with the power of story, call out to me, and I answer them to the extent that my meagre budget allows. I crave the feel of old paper, the brown blotches of old ink stains, the tattered spine, the library stamp, the gift inscription from perhaps 100 years ago or more. Ideally, I would limit myself to first editions, which have that beginning-magic to them even after many decades. Limited as I am to what used copies I can find for thirty dollars or less each (and sometimes a lot less), I will content myself with any old copy whose binding is still intact enough to read without causing further damage. Because I have opted to restrict my reading almost entirely to the forgotten, sometimes opportunities present themselves to obtain the holy grail of the antiquarian book fancier — the signed copy! In a few cases, though, I will have to content myself with whatever copy I can find. A first edition of Walden, for instance, costs more than my annual salary. But mostly I will travel through old books — and my accounts will include not only the words, but the experiences. I will do my best to bring you along on my journey. My second rule? (After all, I did refer to “a couple” of them.) My second rule is to dispense with the thought of a logical sequence to the books I will read. There is no chronology here, though I fully anticipate dialogue between the various authors (some of whom knew and corresponded with, or at least quoted, each other).

TO VARY MY TRAVELS A BIT MORE, I WILL SOMETIMES WANDER INTO MY BACKYARD. I may even set out down Piney Woods Church Road a time or two. My living discoveries — animal tracks, insects, flowers, tree leaves — these I will examine further at home, in light of some field guides that also happen to be some of the earliest published in America. These will include a guide to Southern Wild Flowers and Trees, by Alice Lounsberry, copyright 1901. I managed to win a first edition in an auction in which I was the only bidder (one of the perks of pursuing the obscure and supposedly “out of date”). I can’t wait to open it up and consider everyday nature through the lens of its images and text.

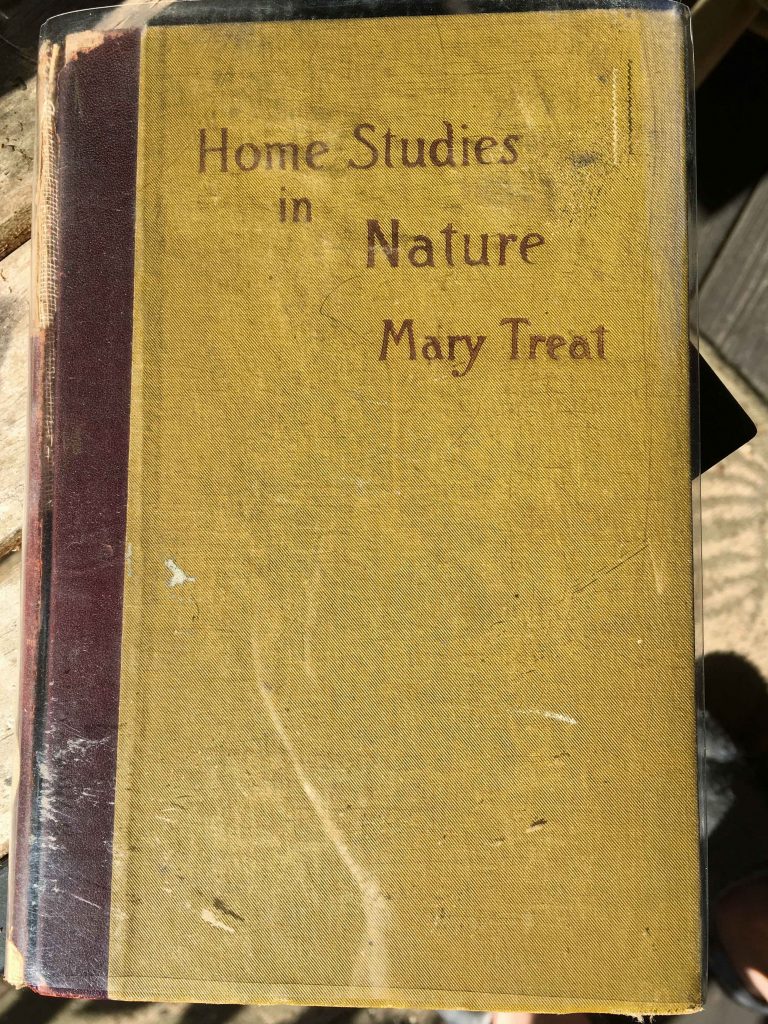

AND SO I BEGIN WITH MARY TREAT, WHO PUBLISHED “HOME STUDIES IN NATURE” IN 1885. I somehow managed to track down a first edition — probably the only edition, for that matter. Like most of these titles, this one is available now in reprinted form, usually printed on demand. But as far as I can tell, since obtaining my copy, no other originals have appeared on the market. That said, the book itself is rather plain: olive drab binding (which looks more yellow-green in the sunlight, in my photograph below), lettering in burgundy across the top, spine (what is left of it) in burgundy, too. A thick folded sheet of transparent plastic both protects my copy and, I suspect, helps prevent its falling apart.

Book Cover

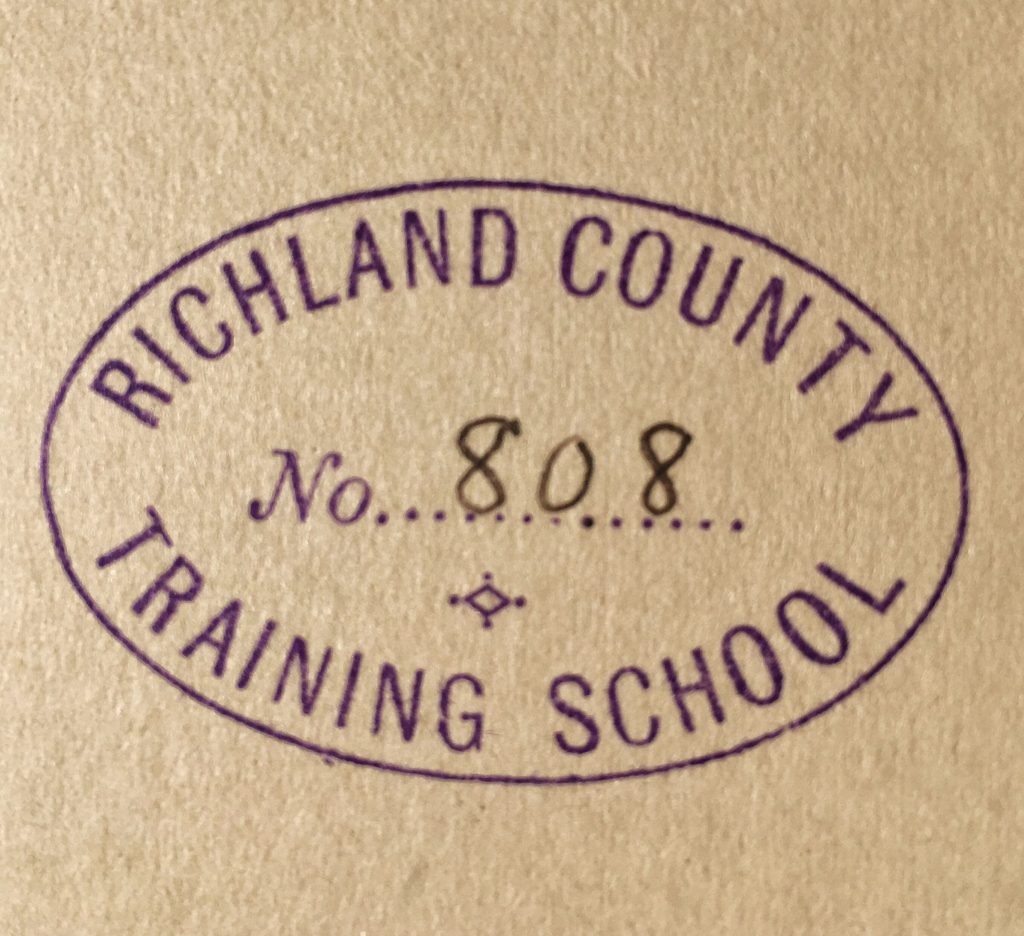

Library Stamp

THE BOOK ITSELF HAS HAD A SOMEWHAT ROUGH HISTORY. It was, at some point, known as “Number 808” and kept on the library shelf of the Richland County Training School. My Google search revealed that it was a Normal School (one that trained future school teachers) in the town of Richland Center, Richland County seat, in the backwoods of Wisconsin about halfway between LaCrosse and Madison. Apart from library stamps inside the front cover and on a library card pocket glued into the back, there is no other writing in the book — no choice underlined passages or random scrawl in pencil or ink. But it did take some beating — about a third of the spine is missing. Was the book popular? Were any readers inspired by it to share some of its ideas or messages with their own pupils?

BEFORE I OPEN THE VOLUME, A FEW WORDS ABOUT THE AUTHOR ARE IN ORDER. Born in 1830 in Trumansburg, New York, she spent most of her formative years in Ohio before returning to New York State and marrying Dr. James Burrell Treat in 1861. The couple moved briefly to Iowa, then settled in Vineland, New Jersey. Beginning in her home’s backyard, and that of a cottage the Treats purchased on the St. Johns River in Florida, Mary Treat explored the natural world. She became renowned for her research and knowledge in entomology and botany (particularly in regard to carnivorous plants). Her botanical and entomological fieldwork took her to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey and the wilds of Florida. Two species of amarilys (one of which she discovered) and two species of ants are named after her. She corresponded with scientists of her day who are still well known — Asa Gray and Charles Darwin, among others. While the public generally knew her as a popularizer of nature study (at a time when the Nature Study Movement was just getting underway), she also conducted experiments and published her findings in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Her first book for a popular audience, “Chapters on Ants”, came out in 1979 and was a collection of essays that had previously appeared in publications like Harper’s. Her second essay collection, “Home Studies in Nature”, came out six years later.

AT LAST, I BEGIN TO READ. After a brief introduction on encountering nature right where you are (including the quote at the beginning of this article), the book begins with a section on birds. There are a lot of bird books from the late 1800s. In fact, a large portion of the early environmental movement emerged from the popularity of birdwatching. Birding also spawned many titles, some of which await reading in my bookcase. Try as I will, I have not been able to connect with my inner ornithologist. I spent a summer working as a seabird interpreter off the Maine Coast, but what I most fondly recall from that time is the rocky, wave-battered coast, the blooming lupines, the strawberry festivals, and the endless used book sales (heaven!), not really the puffins (though I certainly found them adorable). So I was a bit apprehensive as the first chapter on Our Familiar Birds began.

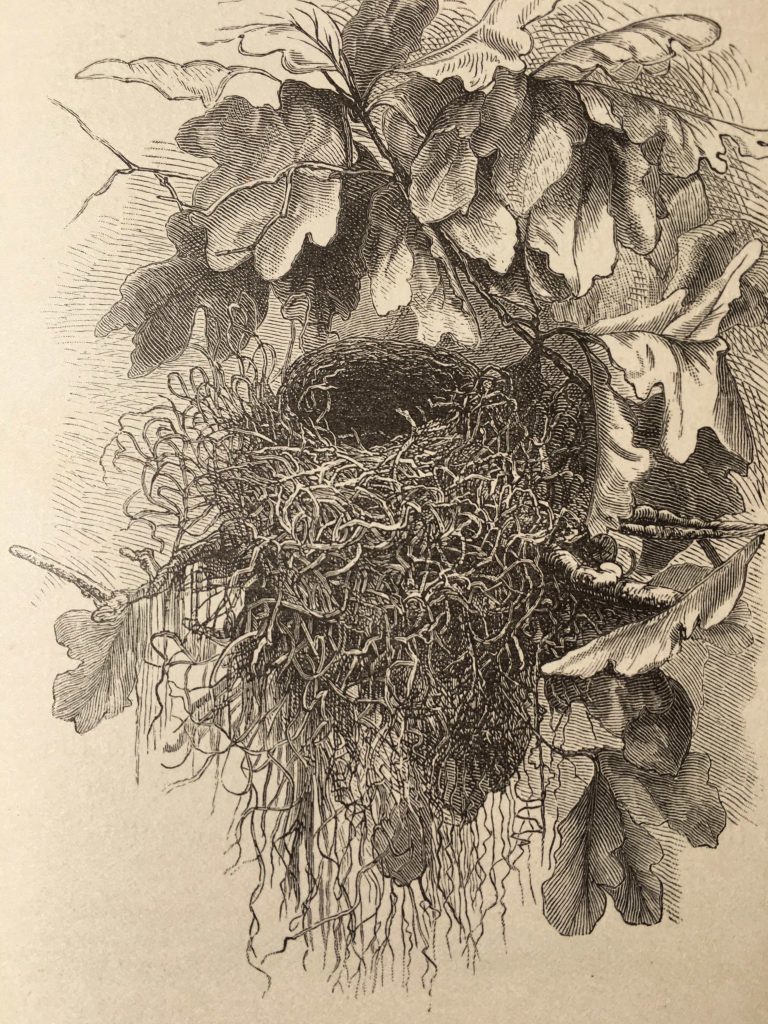

ALREADY I CAN SEE THAT TREAT IS A DELIGHTFUL AND ASTUTE WRITER. I really enjoyed all four of her chapters on birds, including birds of Florida, birds in winter, and the architecture of birds’ nests. I was in awe of how patiently Treat worked on what she refers to as “domesticating” the birds around her, to the point that she could observe their habits closely and begin describing their characters. In so doing, she reveals the birds as living beings, not automatons acting by instincts only. While it is common now for us to ascribe intelligence to birds, in her day that was hardly the norm. In her chapter on birds’ nests, she shares about how different members of the same bird species can construct wildly varying nests — some skillfully crafted, others hastily thrown together. This provides evidence, she argues, that birds can reason and learn — abilities at the time that others would not have attributed to them. Specifically, she writes that

A close observer of birds cannot fail to see that they exercise reason and forethought, not only in the management of the young, but in many other things.

ALREADY, IN 1885, TREAT RECOGNIZES THE HORRENDOUS HUNTING OF BIRDS FOR SPORT. She even expresses a moment of regret that hunters themselves cannot legally be hunted. Compared to that person who shoots birds “from mere wantonness and sport of the chase, the hawk or owl, which takes a bird only to appease his hunger, towers above him in moral rectitude.” I would definitely side with the birds, too.

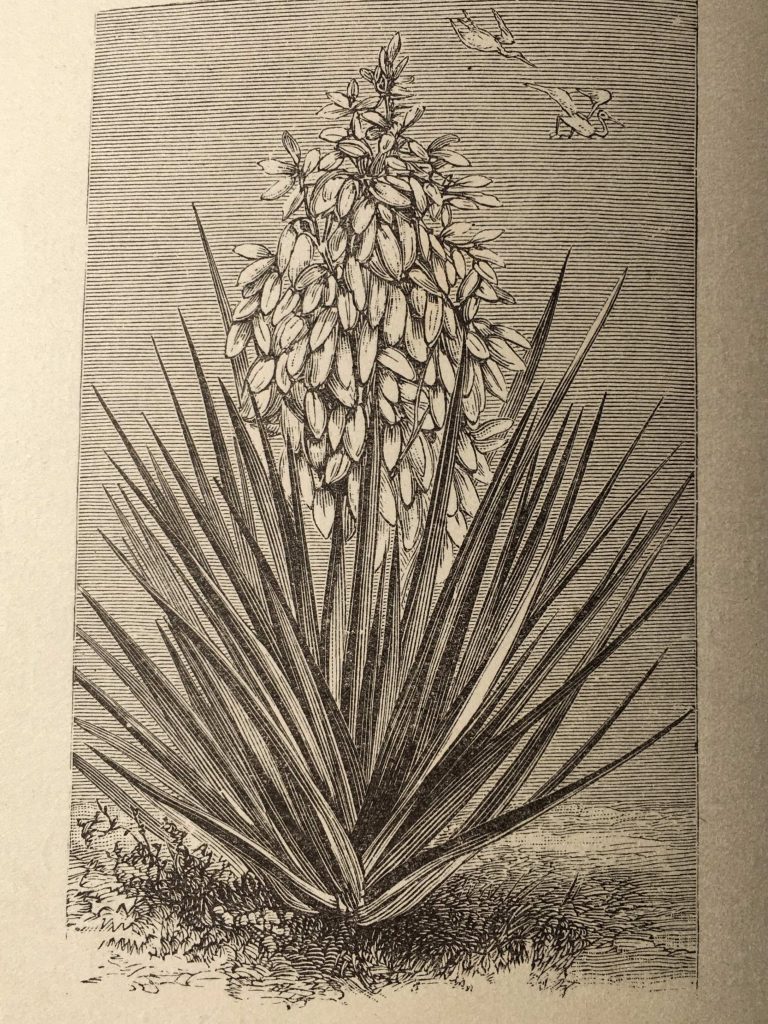

NEXT TIME, AN ADVENTURE WITH INSECTS. The next section of Treat’s book covers some entomological explorations. For now, I will close with one of my favorite illustrations in the book thus far, the Spanish bayonet in flower.