I do not know quite what to make of this book, its rather pretentious title, or its somewhat enigmatic author. I am not even clear that it qualifies as a “nature book”, though it is rich in bucolic scenes of flowering plants and singing birds. I suppose I will share what I know, and let readers figure out the rest on their own.

What is known about the author is that Martha McCulloch-Williams was born near Clarksville, northwest Tennessee, in approximately 1857. Daughter of a wealthy plantation owner, she grew up in luxury, being taught by an older sister instead of attending school. After the Civil War, her family lost much of their wealth. When her already elder parents both died in the mid-1880s, a distant cousin (Thomas McCulloch-Williams) arrived on the scene to help run the farm. Martha’s three sisters soon thereafter decided to sell out instead. Martha, an aspiring writer, moved with Thomas (whom she never actually married) to New York City. In 1882, she published Field-Farings, her first book. It was followed soon thereafter by many works of fiction, including over two hundred short stories. Later, she would gain renown for her domestic works, including a cookbook and household handbook. Eventually, Thomas and all three of her sisters died, then fire swept through her Manhattan apartment, leaving her destitute. She died in a New Jersey nursing home in 1934.

This book, then, is an orphan — her only foray into something akin to nature writing. Its closest relatives, from what I have read thus far, would be Prose Pastorals by Herbert Sylvester (published five years earlier) and Minstrel Weather by Marion Storm (published 28 years later). The work consists of a seasonal round of poetic vignettes of farm landscapes and life in Tennessee. For the first half of the book, the reader is led by the author through each scene, most of which are devoid of other human presences. The language is poetic and sentence structures are sometimes fluid, sometimes awkward, and almost always somewhat difficult to digest. At times, her word choices feel almost like the reimagined Anglo-Saxon of Gerard Manley Hopkins. As the book progresses, scenes of country life (such as haying) replace woodland explorations, and the reader is introduced to a few of the “darkies” who live in the area and presumably are the descendants of former plantation slaves. Always there is a hint of magic, of fairie. At various points, she speaks of elves, gnomes, wood-sprites, and Dyads. It is not that McCulloch-Williams disavows science — rather, she puts science in its place and lets magical thinking have a bit of room, too. Here, she writes about mysterious lights in the swamp, jack o’lanterns as they were known:

Of still, warm nights you may see his fairy lights adance over all the wooded swamp. Now they circle some huge, bent trunk, now leap bounding to the branches for the most part, though, plod slow and fitful, as though they were indeed true lantern rays, guiding the night-traveller by safe ways to his goal. Master Jack is full of treacherous humor. Follow him at your peril. He flies and flies, ever away, to vanish at last over the swamp’s worst pitfall, leaving you fast in the mire.

Wise folk say he has no volition he but flees before the current set up by your motion. We of the wood know better. There is method in Jack’s madness. He knows whereof he does. Science shall not for us resolve him into his original elements turn him to rubbish of gases and spontaneous combustion. Spite his tricksy treachery, he shall stay to light fairies on their revels, scare the hooting owls to silence.

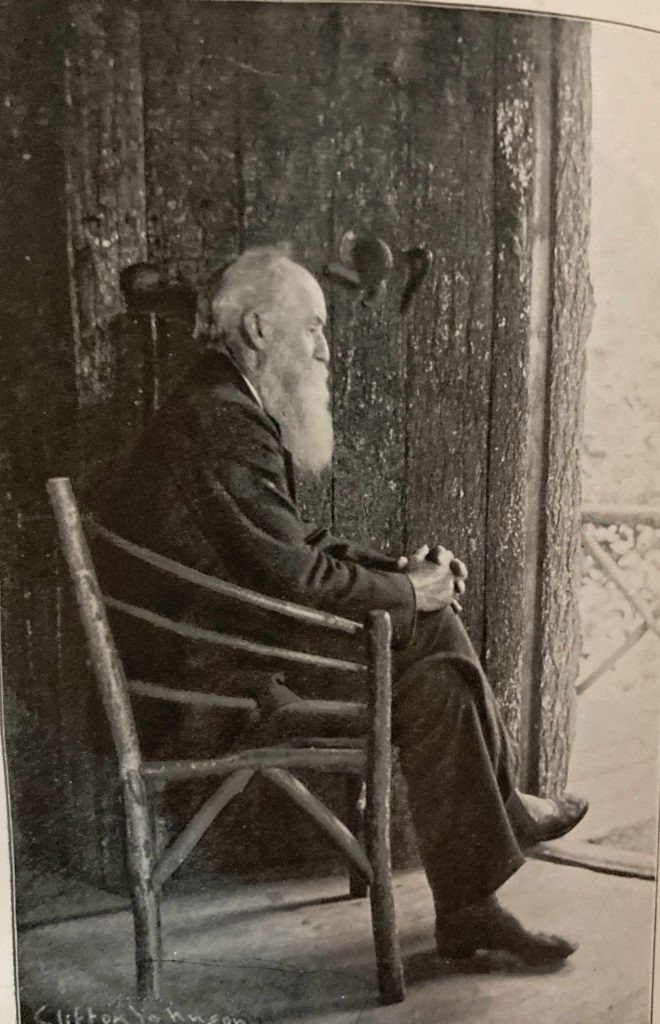

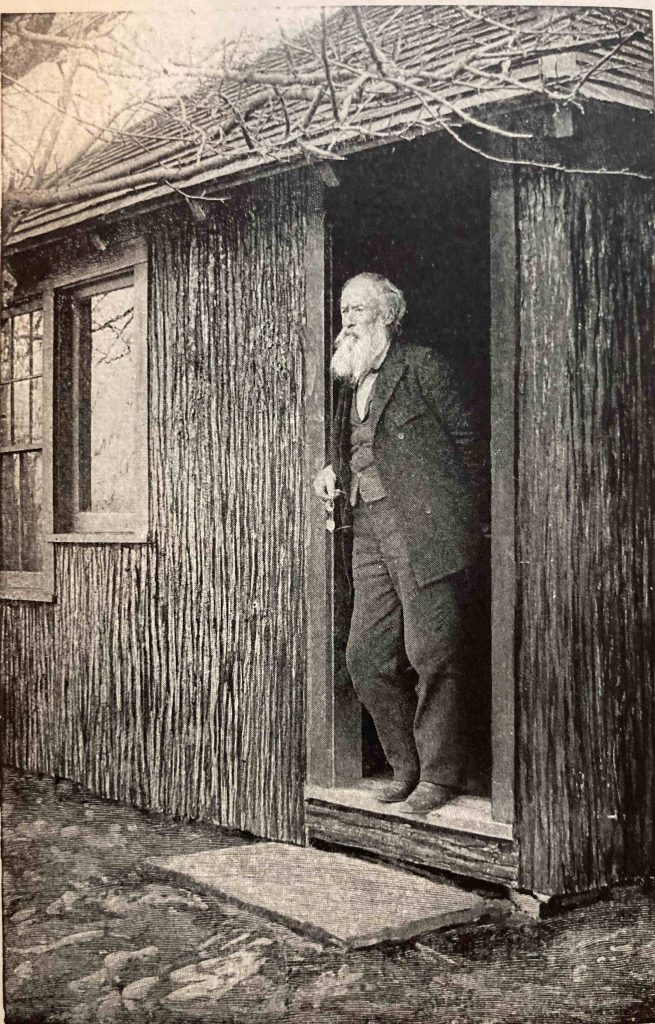

This is not Burroughs, that is certain. Indeed, McCulloch-Williams names no antecedent writers; her only clear inspiration is her childhood on the plantation. Nature, in her eyes, is not some remote wilderness; it is part of the domestic world of her youth. Nature and humans coexist in this landscape — or at least, they do after the original forest was cleared:

Trees give room only through steel and fire. The felling is not a tenth part of the battle. Have you ever thought what it means to wrest an empire from the wilderness ? Do but look at those four sturdy fellows, racing, as for life, to the great yellow poplar’s heart. Four feet through, if one — sap and heart ateem with new blood, just begun to stir in this February sun — it is a field as fair, as strenuous, as any whereon athletes ever won a triumph of mighty muscle.

Once the plow arrives on the scene, so, too, does a host of birdlife. In this vignette, plowing the land not only yields future crops for the landowner but also an immediate gift to the birds:

In flocks, in clouds almost, they settle in each new furrow, a scant length behind the plough, hopping, fluttering, chirping, pecking eagerly at all the luckless creeping things whose deep lairs have suffered earthquake. A motley crowd indeed! Here be crow and blackbird, thrush and robin, song-sparrow, bluebird, bee-martin, and wren. How they peep and chirp, looking in supercilious scorn one at the other, making short flights over each other’s backs to settle with hovering motion nearer, ever nearer, the plough. Who shall say theirs is not the thrift, the wisdom, of experience. How else should they know thus to snatch dainty morsels breakfast, truly, on the fat of the land, for only the trouble of picking it up ? All day they follow, follow. It is the idle time now, when they are not under pressure of nest-making. Though mating is past, yet many a pretty courtship goes on in the furrow. Birds are no more constant, nor beyond temptation, than are we, the unfeathered of bipeds.

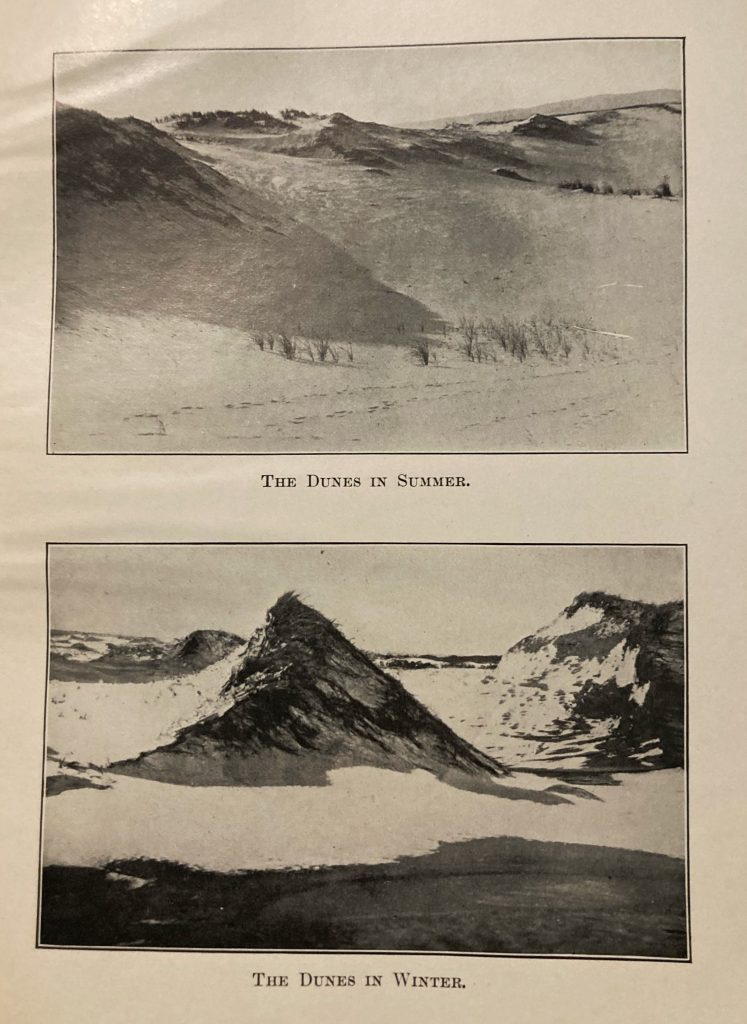

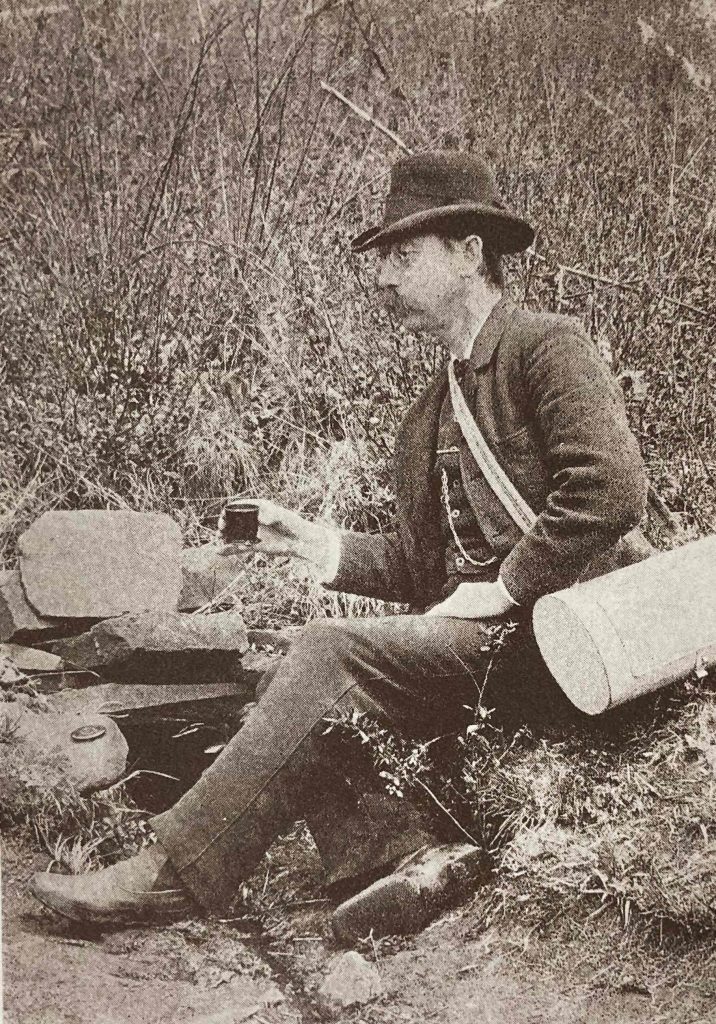

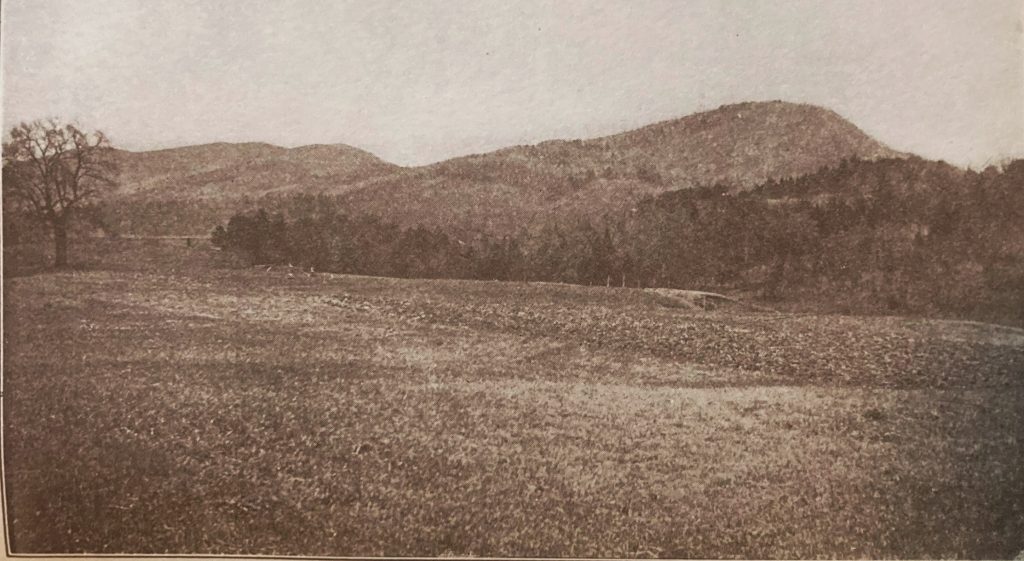

And so the vignettes rush by (or drag, depending upon my own reading mood at the time), from winter into spring, to summer, autumn, and back again, ending the round at Christmastime. The result is a sort of literary Currier and Ives calendar, with scenes a bit like the image below, but without the grand plantation home (no buildings other than cabins are mentioned in this book) and with the Mississippi River replaced with the Cumberland.

The problem with vignettes is that nothing actually happens. The height of drama in the book is a chapter toward the end in which a nighttime hunting party trees some opossums and raccoons. There are no fond memories here, not even tales of sauntering through the woods and some of the discoveries made along the way. As a volume on the edge of the nature genre, it acquaints the reader with Tennessee phenology but tells very little about the actual landscape and names no geographical locations. As sense-of-place literature, it largely fails. If I did not know where the writer grew up, I would not know where the book is set. Only the presence of “darkies” reminds the reader that it is a long way from New England.

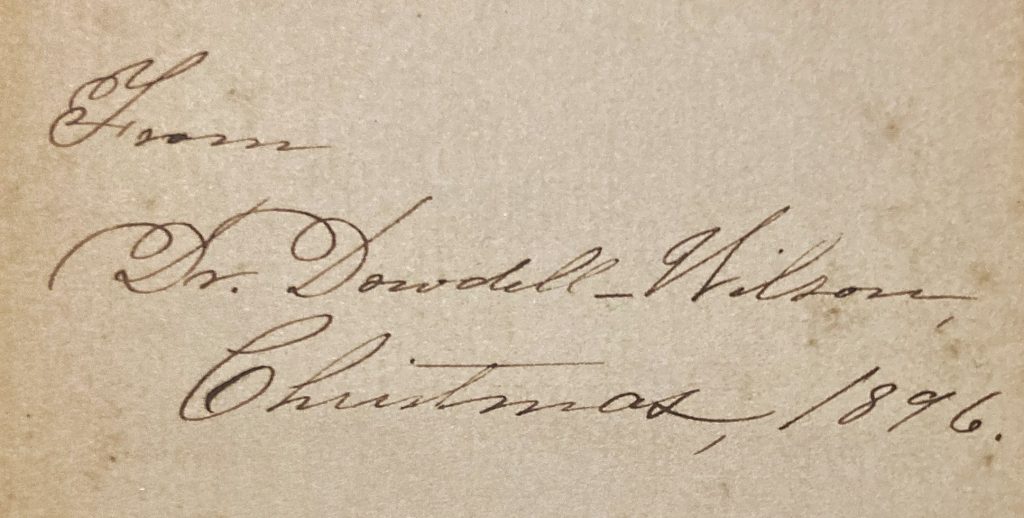

Finally, about my copy of this book: it appears to be the first edition (though I doubt it had a second) and is in remarkably good condition, apart from the very tanned pages. After a series of books with uncut pages, I was surprised to see that this one had probably been read before. I do not know who owned it, but I do know who gave it as a gift: Dr. Dowdell Wilson, Christmas 1896. And I think I found her — yes, her: Dr. Maria Louise Dowdell Wilson, a physician in Troy, New York: alumnus of Boston University School of Medicine (1877) and second wife of Hiram Austin Wilson (1887). She passed away in October 1902.