[The Seminoles’] words are composed of a great number of syllables. Willoughby has given a vocabulary of them in his book Across the Everglades and in this only two words have a single syllable while many run up into eight or more. For instance heron is “wak-ko-lat-koo-hi-lot-tee”; instep is “e-lit-ta-pix-tee-e-fa-cho-to-kee-not-ee,” and wrist “in-tee-ti-pix-tee-e-toke-kee-kee-tay-gaw.” I should think it would take a half hour for a Seminole to ask the time of day, but fortunately he has plenty of time.

There is something very distressing in the gradual passing of the wilds, the destruction of the forests, the draining of the swamps and lowlands, the transforming of the prairies with their wonderful wealth of bloom and beauty, and in its place the coming of civilized man with all his unsightly constructions — his struggles for power, his vulgarity and pretensions. Soon this vast, lonely, beautiful waste will be reclaimed and tamed; soon it will be furrowed by canals and highways and spanned by steel rails. A busy, toiling people will occupy the place that sheltered a wealth of wild life. Gaily dressed picnicers or church-goers will replace the flaming and scarlet ibis, the ethereal egret and the white flowers of the crinums and arrowheads, the rainbow bedecked garments of the Seminoles. In place of the cries of wild birds there will be heard the whistle of the locomotive and the honk of the automobile.

We constantly boast of our marvelous national growth. We shall proudly point some day to the Everglade country and say: “Only a few years ago this was a worthless swamp; to-day it is an empire.” But I sometimes wonder quite seriously if the world is any better off because we have destroyed the wilds and filled the land with countless human beings. Is the percentage of happiness greater in a state of five million inhabitants than in one of half a million, or in a huge city with all its slums and poverty than in a village? In short I question the success of our civilization from the point of view of general happiness gained for all or for the real joy of life for any.

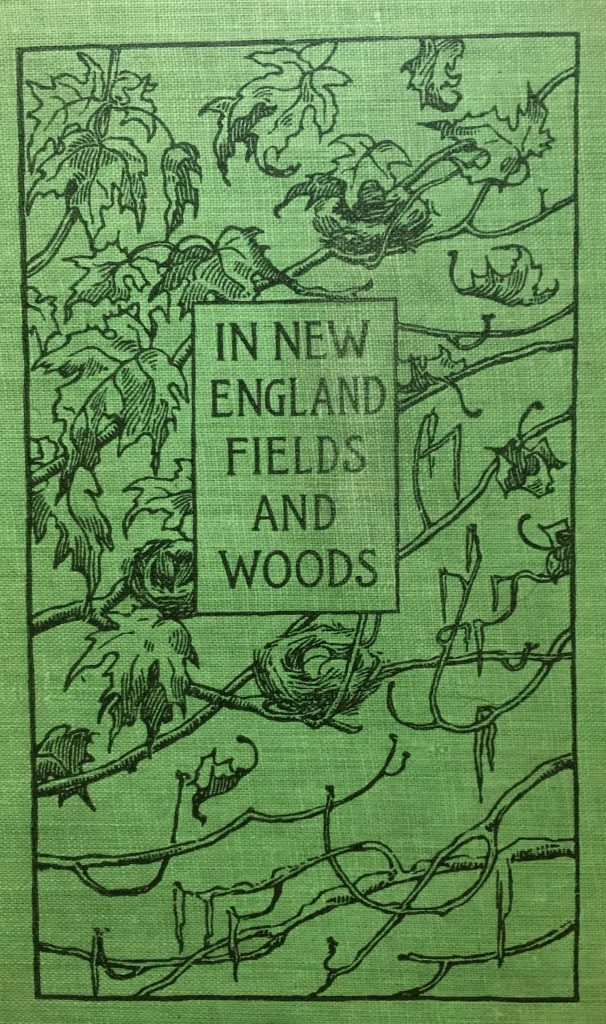

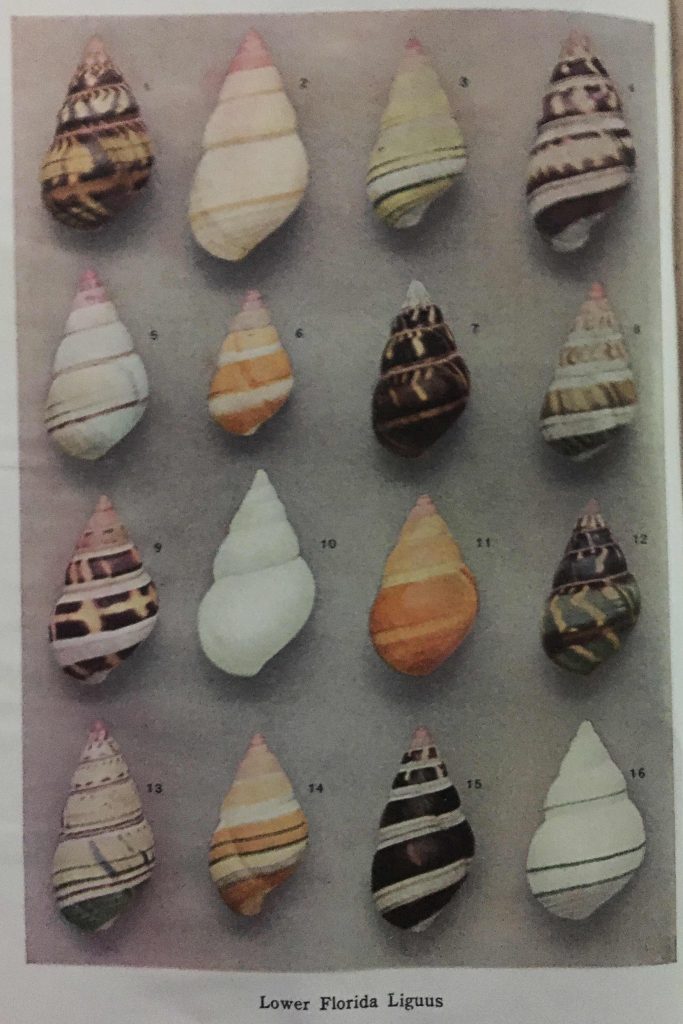

IN THIS TIME WHEN HAPPINESS IS RARE INDEED TO FIND, SIMPSON’S WORDS SPEAK DIRECTLY TO MY HEART. Opening the first pages of “In Lower Florida Wilds”, I developed an immediate affinity for the author. Though I know relatively little about him yet (his published biography is on its way to me now), through the pages of this book I have found him to be sincere, affable, thoughtful, perceptive, caring, and a bit self-deprecating to boot. His deep love for nature flows through these pages — along with his keen scientific mind and eye. Over the course of nearly 400 pages and over 60 black and white photographs (not to mention a color frontispiece of Simpson’s beloved tree snails), the reader travels through the geologic story of South Florida and then the myriad terrestrial and marine ecosystems found in the region. Through it all, Simpson mourns again and again the tragic demise of Florida’s wild animals, plants, and places. He seems largely resigned to their passing, though he does offer a ray of hope that conservation might yet be possible:

This locality [along the south shore of mainland Florida] is one of the last resorts of some of our most beautiful and interesting wading birds. Here in days gone by resorted vast numbers of gorgeous flamingos, scarlet ibises, roseate spoonbills, and roseate terns. This was one of the chief breeding places of the ethereally beautiful egret…and the even more perfect snowy heron…. Owing to woman’s vanity and man’s greed they are now well-nigh exterminated….

The entire region (which is of little value for anything else) should be set apart by the federal government, as a great bird reservation, but even then it would be difficult enough to protect the birds within it, for the same men who killed Bradley [a murdered bird warden whose tale is told here] would not hesitate to do the same by any other warden.

ON A LIGHTER NOTE, SIMPSON IS ALSO A MARVELOUS TELLER OF TALES OF HIS EXPERIENCE IN THE SOUTH FLORIDA WILDS. One of my favorite stories, though, happens to him in Key West, where he finds himself collecting lovely shells — of still-living snails — with quite comicl consequences:

I once made a cruise in the schooner Asa Eldridge from Bradentown, Florida to Honduras and on a Sunday morning while lying at Key West I strolled over to the north side of the island. As I approached I saw from a short distance that it was everywhere a mass of glowing violet color and then I found it to be covered from below tide to well out on the land with fresh Hanthinas. All the depressions and pot holes in the rocky shore were filled — in places several feet deep. A vast community or gathering of them probably extending for miles had stranded the night before on the beach. It was the most astounding sight in the way of molluscan life I had ever seen and when I recovered from my surprise I proceeded to collect specimens. Lacking any receptacle in which to put them I used my handkerchief, then my new straw hat, then one pocket after another of my fresh white linen suit, and when fully loaded I started for the schooner.

The day was hot, and soon the snails seemed to be melting. To my horror violet blotches appeared on my coat and trousers, spreading rapidly until the purple juice from the animals actually ran down and filled my shoes! I reached the city as the church bells were ringing and I tried to evade people by taking alleys and back streets but everywhere I met groups of churchgoers who stared at me in astonishment. They no doubt took me for an escaped lunatic. It seemed to me that Key West had a population of a hundred thousand and all churchgoers. Having run that gauntlet and reached the vessel our crew greeted me with shouts and laughter. My smart suit was ruined, nor could I even wear it around the vessel without being derided — but I had the satisfaction of cleaning up over two thousand fine Janthina shells.

THOUGH I DO NOT PICTURE SIMPSON AS A CHURCHGOER HIMSELF, HE WROTE OFTEN OF THE INSPIRATION AND WONDER HE FOUND IN NATURE. For instance, in this passage, he wrote admiringly (and well ahead of his time) of an intelligence operative throughout the natural world — not the intelligence of a supernatural designer, but of the plants and animals themselves:

It seems to me that there is a soul throughout nature, that the animals, and I like to believe, the plants, to a certain extent, think, something in the same manner that human beings do. Howe invents the sewing machine, Bell the telephone, McCormick the reaper — all devices to perform some service to the benefit of man. A palm sends its growing stem deep into the earth and buries its vitals to protect them from fire; the mangrove raises itself high on stilted roots in order than it may live above the water and breathe; an orchid perfects a complicated device to compel honey-loving insects to cross-fertilize its pollen. Animals resort to all manner of tricks to conceal themselves from their enemies. All these work not merely for themselves but for the benefit of the race to which they belong. If the work of man is the result of thought that of animals and plants must be also in some lesser degree. If man developed from a lower animal, the superior from the inferior, where may we draw the line between reason and instinct?

Consider, too, the paragraph below, in which Simpson (an “old man” at 73, though he lived another 13 years after this) celebrates the deep joys that come from going on wilderness adventures under primitive conditions in the swamps of south Florida:

Why should an old man, past the age when most persons seek adventure, leave a comfortable home and plunge into the wilderness to endure such hardships? What rewards can he receive for it? I never return utterly warn out from such a trip but that I vow it is the last. But in time the hardships are forgotten and recollections of the pleasant features only remain and I am ready to start again. There is in all this a sort of fascination not easy to explain — the relief that comes from being away from all the restraints and artificialities of communal life — and then, the “call of the wild.” There is a wonderful inspiration in the great out of doors. Every feels it — some more, some less. Personally I cannot resist the call and must respond when I hear it and understand its meaning.

Here is a lovely passage in which Simpson expresses a childlike wonder at the experience of being outdoors at night:

I love the night with its silence, its strange sounds, its beauty and mystery. It has an infinite attraction for the devotee of nature: al that he sees, hears, and feels are so different from the experiences of the daytime; he seems to be in another world…. Much of the wonder and beauty of the night consists in what is only half seen, in what is partly suggested, leaving the imagination to do the rest.

Itis then largely because of the stimulation of the imagination that the night is so wonderful. Under its spell we create a world of our own and revel in the make-believe — like the children of a larger growth that we all are.

Finally, I will close with this marvelous passage in which Simpson speaks of his reverence and devotion toward nature, something he fears that too many specialist scientists have lost:

It was in the wilds that Humboldt, Darwin, Wallace, Bates, Spruce, and the splendid company of the earlier and greater naturalists studied and worshipped Nature. They were interested in every phase and detail of it; their contact with it made them broad and big and able to see the great truths. There are many specialists who study intensively some small group of animals or plants until they know more about it than anyone else, but they have too little general scientific knowledge, and they care too little for the great scheme of nature. In fact they are too little. They may slave on the anatomy or heredity of a few things but they neglect the larger questions of environment and distribution. They are closet students — scientists, not naturalists; their whole occupation is business; they find neither beauty nor charm in it. They dig in a tunnel and see nature through a pinhole….

I do not want to investigate nature as though I were solving a problem in mathematics. I want none of the element of business to enter into any of my relations with it. I am not and cannot be a scientific attorney. In my attempts to unravel its mysteries I have a sense of reverence and devotion, I feel as though I were on enchanted ground. And whenever any of its mysteries are revealed to me I have a feeling of elation — I was about to say exaltation, just as though the birds or the trees had told me their secrets and I had understood their language — and Nature herself had made me a confidant.

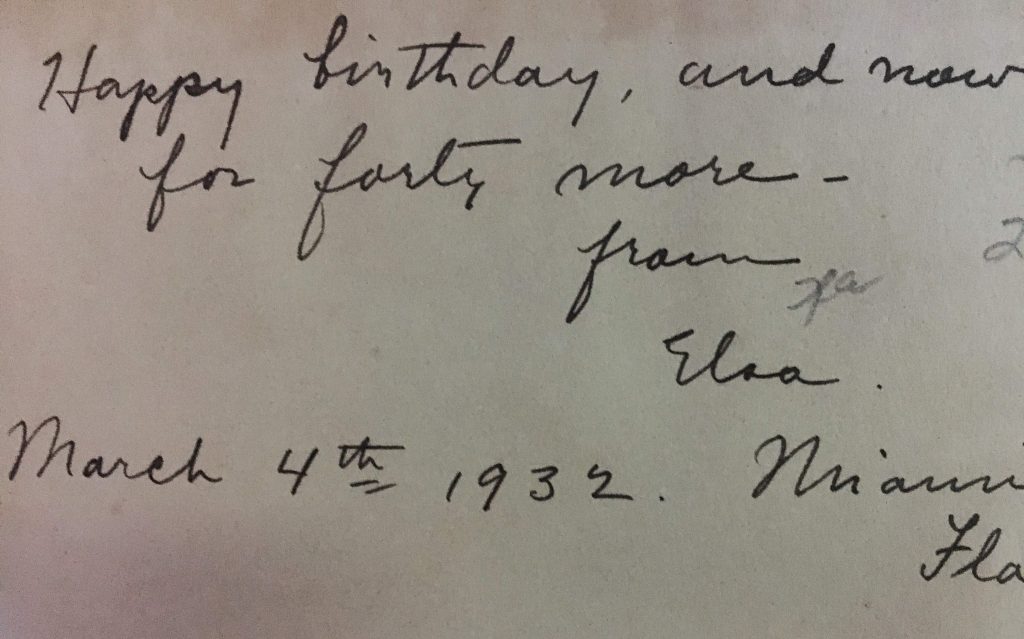

birthday note to unknown recipient from Elsa, 1932, on flyleaf of book (right)

REGARDING MY COPY OF THIS BOOK, IT HAS HAD A ROUGH LIFE, THAT’S FOR SURE. The covers bow out a bit, and the pages have recovered from a good soaking. Reading it, I do not get that pleasurable sensation of being able to bend back the top corner of the page and advance quickly through the text; pages turn only singly. Though there is no salt brine, and my wife assures me the damage is not great enough to reflect a complete immersion, I cannot shake the image of this book having been used as a life preserver, cast overboard to a drowning would-be swimmer somewhere off the Florida Keys. I suspect the truth is as prosaic as an unexpected afternoon rainshower falling on a book left on a table on the back patio.

In terms of its history, the only event in its existence of which I can speak (besides its publication in 1920) happened on an unknown recipient’s birthday, March 4th, 1932, when Elsa gave someone this book on her (or his) 40th birthday, in Miami, Florida.

As another note from one who has taken a fancy to Charles Torrey Simpson — the friendship can be a costly one. This book was not terribly costly — about $40. However, his other two books, published in 1923 and 1932, are another matter. I have learned that any book published after 1922 is not available as a free scan online, nor are facsimile copies sold on Amazon or elsewhere. The book is truly out of print. For those craving more of this author, the choices are hunting university libraries for copies, or buying copies. I opted for the latter. I snatched a copy of his 1932 book for only $40, but his 1923 book was a “steal” in a signed copy in good shape for “only” $135. I think in the future I need to stick to less desirable authors — the disreputable riffraff of the literary naturalist community, if there is such a thing.