What familiarity with the elements and with natural features of the earth the migrating birds must acquire — with winds and clouds, with mountain chains and rivers and coast lines! They know the landmarks and guide-posts of two continents and can find their own way. The whistle of curlew, or the honk of wild geese high in the air, seems a greeting out of the clouds from these cosmopolites, to us, sitting rooted to the earth beneath. A flock of wild geese on the wing is no less than an inspiration. When the strong-voiced, stout-hearted company of pioneers pass overhead, our thoughts ascend and sail with them over the roofs of the world. As band after band come into the field of vision — minute glittering specks in the distant blue — to cross the golden sea of the sunset and disappear in the northern twilight, their faint melodious honk is an Orphean strain drawing irresistibly.

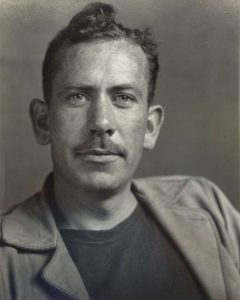

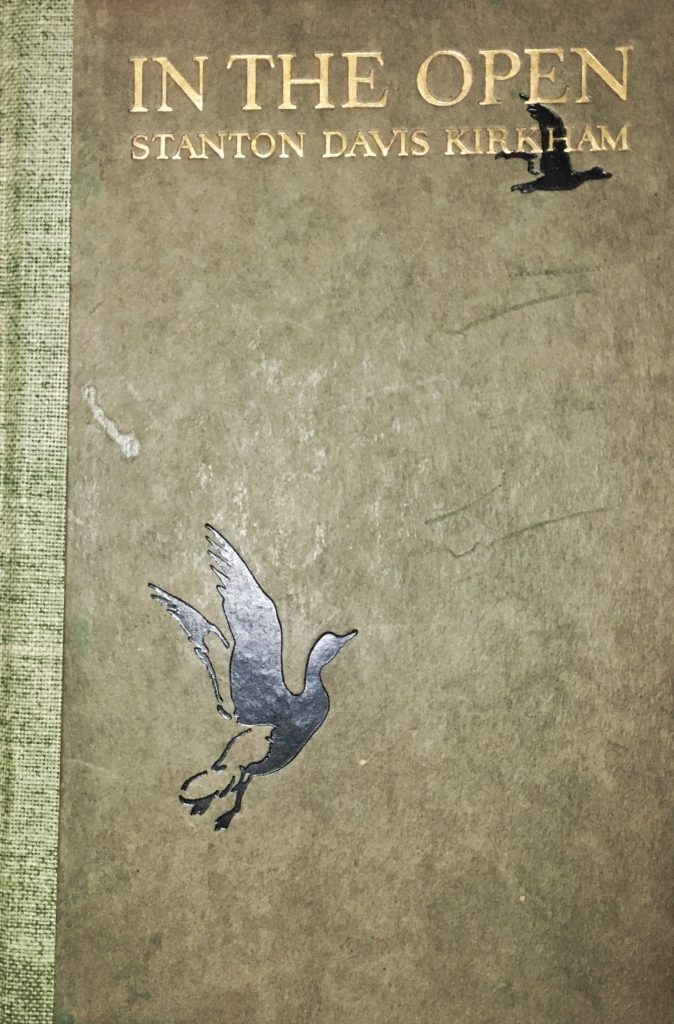

AND SO, TOO, WITH THIS STUNNING IMAGE AS ITS FRONTISPIECE, KIRKHAM’S “IN THE OPEN” DREW ME IRRESISTIBLY IN. My excitement about the book mounted as I read the opening lines of the first essay, The Point of View, poetically celebrating the opportunities to engage with the exuberant energy and vitality of nature around us:

Nature is in herself a perpetual invitation: the birds call, the trees beckon and the winds whisper to us. After the unfeeling pavements, the yielding springy turf of the fields has a sympathy with the feet and invites us to walk, It is good to hear again the fine long-drawn note of the meadow-lark — voice of the early year, — the first blue-bird’s warble, the field-sparrow’s trill, the untamed melody of the kinglet — a magic flute in the wilderness — and to see the ruby crown of the beloved sprite. It is good to inhale the mint crushed underfoot and to roll between the fingers the new leaves of the sweetbrier; to see again the first anemones — the wind-children, — the mandrake’s canopies, the nestling erythronium and the spring beauty, like a delicate carpet; or to seek the clintonia in its secluded haunts, and to feel the old childlike joy of lady’s-slippers.

ALAS, POOR KIRKHAM. Having read close to forty works of natural history now, I have to recognize that this book opens with two strikes against it. Firstly, it is set in New England — what is worse, Massachusetts — just like practically half of the nature books from its day. And then it relies heavily on the round-of-the-seasons motif, a tired structure for natural history accounts of the time. What is more, there is no reference to places; I suppose Kirkham’s idea was that his book encounters with nature might be anyone’s, and particularities of locale did not matter. Only in two essays near the close of the book — The Mountains and The Forest — does the author stray further afield, to the Rockies and the Sierras, respectively. (Even then, if not for brief name-dropping of the two mountain ranges midway through each chapter, I would not know where they were set.) Oh — and in a bit of bait-and-switch, the frontispiece painting is the only color image in the book, and Luis Agassiz Fuertes’ only contribution to it.

THE THIRD STRIKE, THOUGH, IS ITS RATHER FORMULAIC PROSE AND OVERLY FAMILIAR NATURE ENCOUNTERS. His writing is poetic and aesthetically rich, yet somehow falls mostly flat in the long run. Kirkham makes abundant mention of mythological figures, and fills his pages with names of plants and birds — clearly he knew his Greek and Roman legends and his New England natural history in abundant measure. But somehow, he rarely manages to bring something new to the genre of nature writing. He offers the reader vivid sensorial descriptions — the book does not want for adjectives. He shares many facets of the natural world, but they are ones I have encountered elsewhere — cowbirds laying their eggs in the nests of other species, caterpillars falling prey to ichneumon wasps, squirrels gathering acorns. He even includes several pages of observations of red and black ants fighting each other in a barn — the red ants evidently attempting to enslave the black ones (which he disturbingly refers to again and again as “negroes” — but we will leave that faux pas — or perhaps even bit of intentional racism — alone for the time being). But he brings no new realization to the story — Thoreau beat him to it with an ant battle scene in “Walden” several decades earlier.

OCCASIONALLY, THOUGH, KIRKHAM SUCCEEDS — AT LEAST, FOR THIS PARTICULAR READER. Kirkham devotes an essay to Pasture Stones. Perhaps it is the geologist in me that enjoyed his appreciation of them and his invocation of the last Ice Age. They infuse the New England pasture landscape with a sense of deep time, and Kirkham explores this here:

There is a rustic notion that boulders somehow grow, in some inexplicable manner enlarging like puffballs and drawing sustenance from the earth — and what could be more puzzling to the uninitiated than the presence of these pasture stones? His was an ingenious mind who conjured up that remote ice age from this fragmentary evidence and derived a history from these scattered letters and elliptical sentences. It was like tracing the stars in their origin.

It takes a bold imagination, indeed, to see these familiar fields and woods overlaid with a mile’s thickness of ice; to recognize here in this present landscape a very Greenland, redeemed and made hospitable. There was need of a solid foundation of fact, patiently garnered, before such an arch of fancy could be sprung. What chaos and desolation once reigned here, only these boulders can tell. Here was a frozen waste as barren as the face of the moon. But beneath lay the soil that was to nurture the violet and the hepatica. There was a fine satisfaction in riding a miracle like this to earth, to corner it and see it resolve itself into the working of natural laws.

Here is another passage I enjoyed, in which Kirkham muses on a bit of driftwood he found on an ocean beach. Again, he writes about the power of imagination, imbuing natural objects like pasture stones and pieces of wood with rich stories steeped in the magic of time’s long passage:

I take home a piece of driftwood, for no ordinary fire but to kindle the imagination, for it is saturated with memories and carries with it the enchantment of the sea. To light this is to set in motion a sort of magic-play. True driftwood has been seasoned by the waters and mellowed by the years. Not any piece of a lobster-pot, or pleasure yacht, or, for that matter, of any modern craft at all is driftwood. It must have come from the timber of a vessel built in the olden time when copper bolts were used, so that the wood is impregnated with copper salts. That is merely the chemistry of it. The wood is saturated with sunshine and moonlight as well, with the storms and calms of the sea — its passions, its subtle moods; more than this, it absorbed of the human life whose destiny was involved with the vessel — the tragedy, the woe. It had two lives — a forest life and a sea life. By force of tragedy alone it became driftwood. Winter and summer the sea sang its brave songs over the boat and chanted her requiem at last as she lay on the ledge. This fragment drifted ashore out of the wreck of a vessel, out of the wreck of great hopes, out of the passion of the sea.

AT TIMES OVERWROUGHT, AT TIMES TEDIOUS, AT TIMES NEARLY ELOQUENT, KIRKHAM’S BOOK LEAVES ME WITH A SENSE OF MISSED POTENTIAL. Perhaps, if he had chosen as a theme a collection of brief musings and impressions of natural objects and scenes, along the line of the pasture stones and driftwood, the book would have been more engaging. Like nearly every nature writer I have encountered so far, Kirkham clearly had moments of insight that he successfully transferred to the page. Yet his work, collectively, does not (in this volume, at least) sustain the wonder and intensity that it occasionally manages to convey so well. My favorite page, without question, is the stunning frontispiece painting by Louis Agassiz Fuertes.

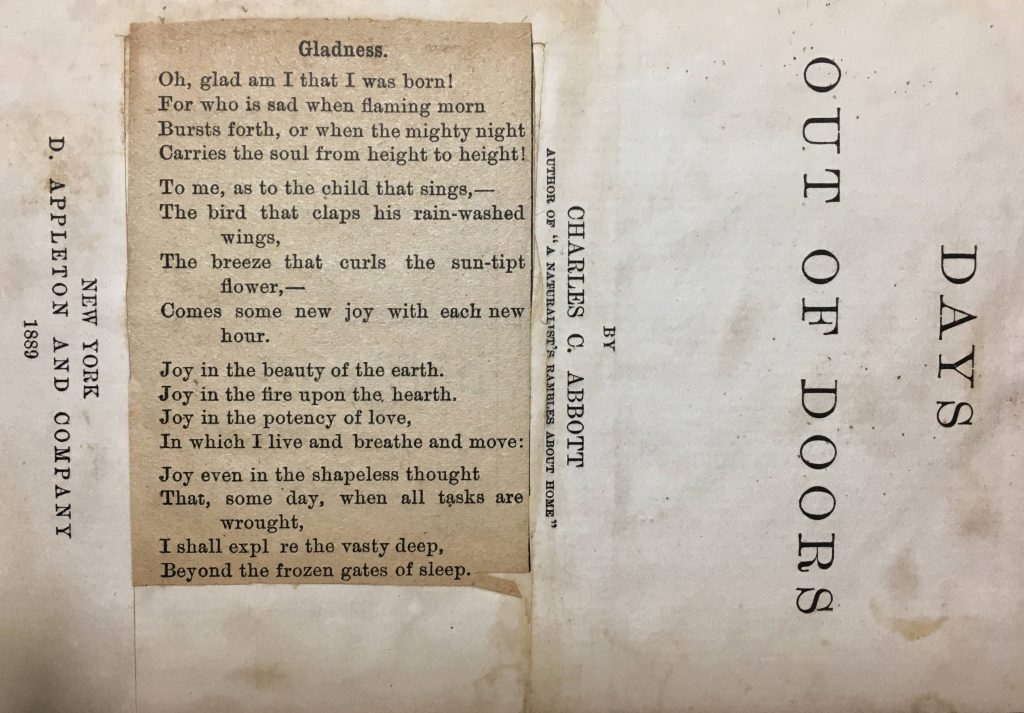

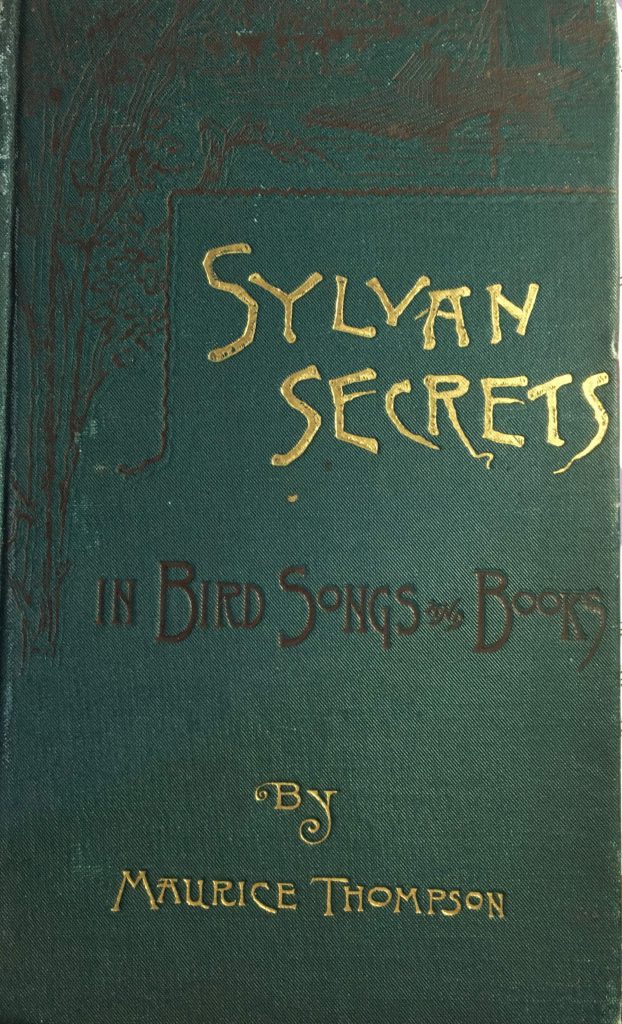

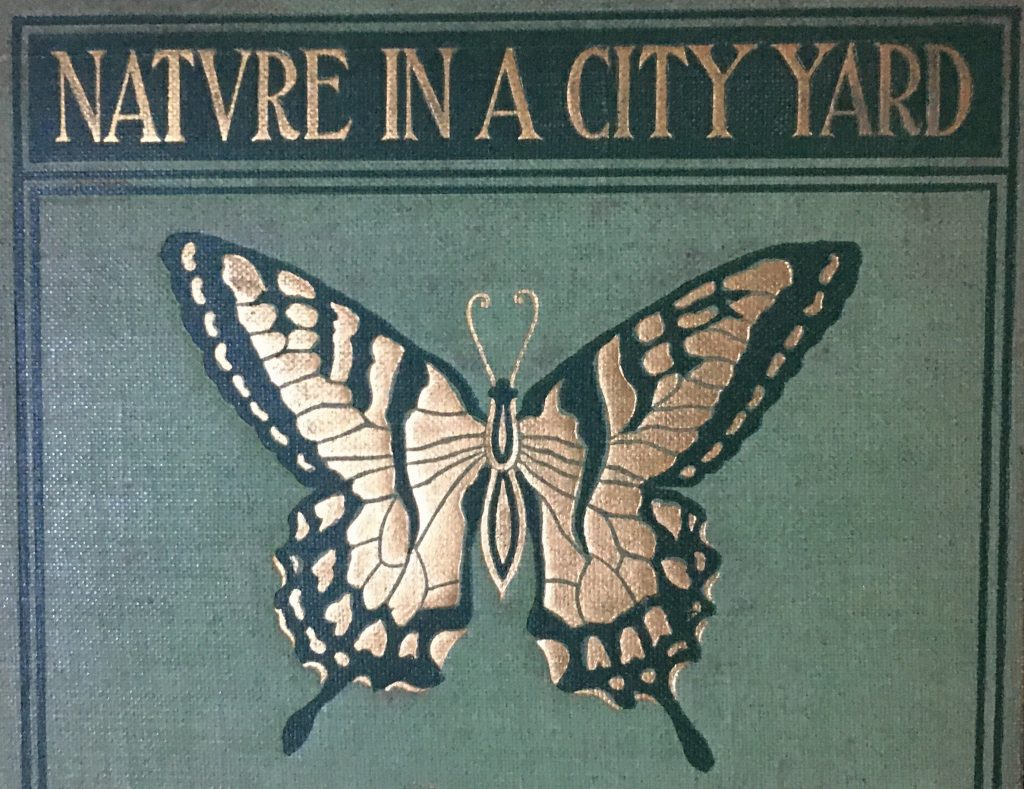

MY COPY OF THIS BOOK IS A FIRST (ONLY?) EDITION. Unlike the pasture stones Kirkham wrote about, this volume has no marks showing its journey. It is a lovely book, visually; the cover is so enticing in its simplicity (in an age of sometimes ornate gilded cover art), and the pages so thick and robust, with deckled edges on bottom and side and gold along the top. It would have made a fine gift for a discerning lover of nature — ideally, one who had not previously read half a dozen other books about Massachusetts through the seasons.