SISTER ELLEN had never seen the trailing arbutus in its native woods. The rills and brooks near the city had been so greatly “improved” by their contact with civilization that scarcely a leaf remained to suggest the sweetness of the Mayflower. It had retreated before the ever-advancing army of flower pickers with baskets and grasping hands. With it had gone the pinxter- flower, and even the more rugged columbine had been driven to establish itself on the steep sides of the gorges, where no human foot had ever trod...

…one azalea remained in our near-by woods and a chosen few knew its station. It served us for a calendar. When its buds were pink at the points we knew that the north slope of Tower Hill would be covered with arbutus and the south side with pink azaleas. With baskets and small black pail we started, Sister Ellen, the Doctor and I.

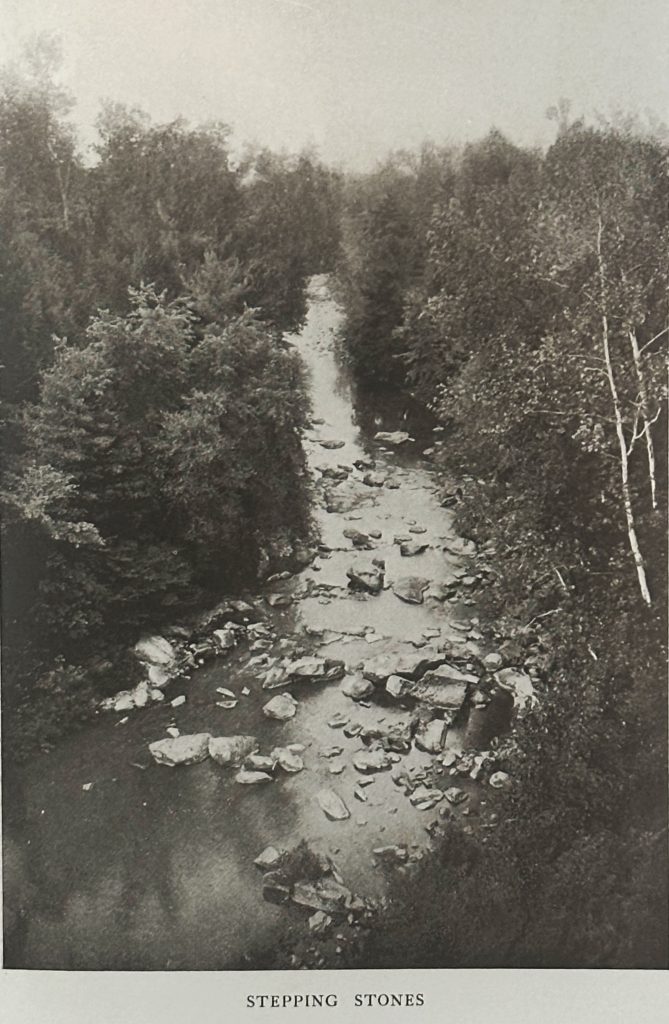

We followed the course of the stream, making our own path as we went. Ellen pounced upon the first promising bit of green which showed under the carpet of dead leaves. It proved to be a small plant of arbutus too young to have a blossom. “Wait till we get farther down,” I advised knowingly.

We were coming to the arbutus country, by the signs which we who had been there aforetime recognized. Soon now the patient scrapings of Sister Ellen would be rewarded. We must keep near her and catch the glow of her first “fine frenzy.” For the twentieth time she dropped to her knees among the dead _ leaves. This time was her reward. There lay the most exquisite clusters, like pink ivory, delicately wrought. The faint elusive perfume enslaved us all. Down on your knees and offer homage to this woodland princess!

The turn of the century (from the 19th into the 20th) marked the apex of the Nature-Study Movement. Its purpose and principles are worthy of many blog posts if not a book or two. Inspired in part by Liberty Hyde Bailey, professor of horticulture at Cornell University, Nature-study was an approach to teaching children about the natural world through direct observation and guided inquiry. Led by an inquisitive teacher (who was likely far from being a nature expert herself), children would ramble out-of-doors, find a particular thing of interest (insect, plant, stream, etc.), and study it closely. They might be asked to sketch the object, and/or come up with different questions to ask about it. The intention was far less to teach natural history content than it was to guide children into a greater appreciation and wonder about the everyday natural landscape all around them (whether in rural places or cities). Other figures in the New York State branch of Nature-study education (there was another that emerged in Chicago) included author/educator Anna Botsford Comstock (who wrote The Handbook of Nature Study, still in print) and her husband, the entomologist and author John Henry Comstock, to whom The Brook Book was dedicated. (Comstock is “the Doctor” in the passage above.) Mentored by Bailey and the Comstocks, sisters Mary Rogers Miller (1868-1971) and Julia Ellen Rogers (1866-1958) pursued careers in Nature-study, first in Ithaca, New York, and later in Long Beach and Los Angeles, California, respectively. Early in their careers, while still in Upstate New York, they both authored nature books of their own. Encouraged by Liberty Hyde Bailey, Julia Ellen wrote a general book on trees, covering their structure, propagation, and care, along with a guide to the most common trees of the Northeast. Mary, inspired by John Comstock, wrote a book on streams with an emphasis on aquatic life, especially insects. Julia Ellen does not mention her sister, but Mary refers to “Sister Ellen” in several places, including the text above, which tells the story of Julia Ellen’s first encounter with blooming arbutus.

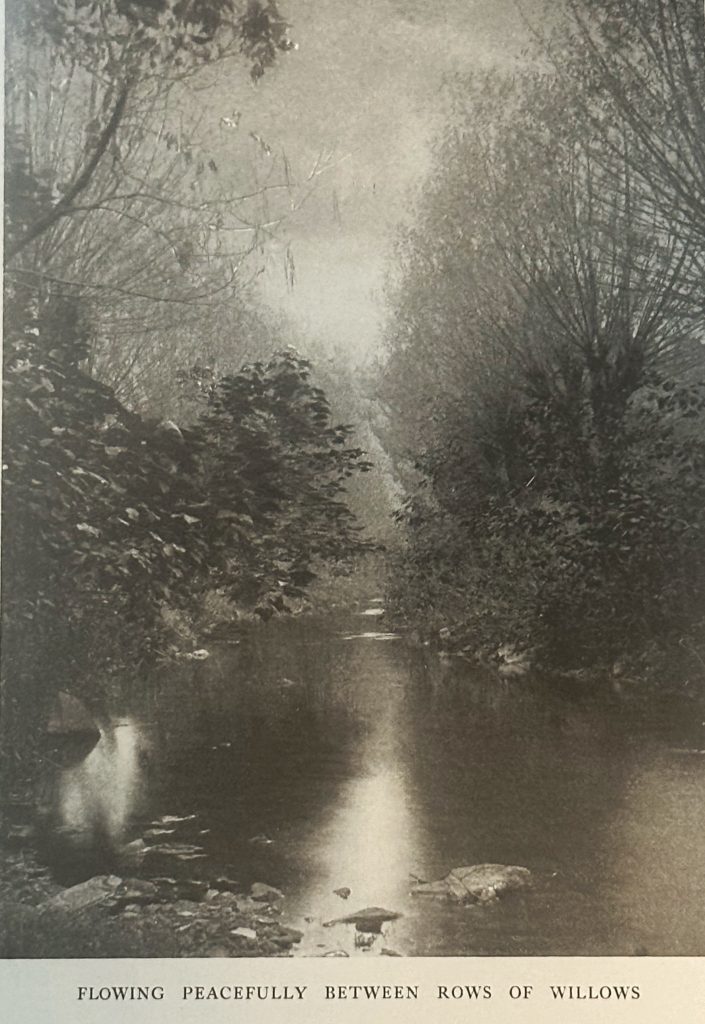

At first, I found The Brook Book a puzzling read. It consists of a series of vignettes chronicling nature expeditions, arranged seasonally to begin with spring and end with wintertime. But while her sister devoted several pages to explaining the design and rationale behind Among Green Trees, Mary explained the purpose behind her own book in much simpler terms: “Throughout a year a brook is captivating. It is as companionable as a child, and as changeful. It hints at mysteries. But does it tell secrets other than its own? Does it tell where the wild things come down to drink? Does it tell where the birds take their baths, or where the choice wild flowers lurk? I fain would know the story of its playfellows and dependents.” Between the lines of this playful, teasing account is some hint, perhaps, of her audience might be — the child within all of us, old and young alike.

That said, the first several dozen pages favored the young. I enjoyed the writing, but learned nothing new and encountered little of note. Then I came upon a chapter about how spiders spin their webs. Mary quoted briefly from a nature guidebook that explained how orb weavers begin constructing their webs by spinning a series of guy lines, using dry and rigid thread so that they can support the entire structure while being easy for the spider to traverse readily. Only then does the spider spin its web of sticky and elastic threads — not in concentric circles, but instead a continuous spiral. She then set out to find an orb web herself and see how it was built. Indeed, her own observations matched what she head read. But reading it alone was not enough. For my own part, reading her book almost 125 years after it was written, I confess that I had never stopped to think about how spiders build their webs. Somewhere along the line, I just assumed the webs consisted of a series of concentric circles, not single spirals. There was how it was done — hiding all this time in plain sight, in a web on the railing of a bridge over a brook. “After seeing all these things happen,” Mary observed, “we know the philosophy of the two kinds of threads, but the wonder of it is still with us.” And that wonder is the the ultimate prize of the Nature-study enthusiast. The book contains other intriguing discoveries, including a hypothesized “cow shed”, a “curious, muddy-looking” object on the stem of a shrub that John Comstock claims was built by ants to house a herd of aphids. (The aphidse secret a sugary substance that the ants feed on, receiving in exchange protection from would-be insect predators.) I admit to being skeptical regarding that one.

One of my favorite passages in the book, though, is a stern critique of a neighbor’s utilitarian outlook on the value of nature — an anthropromorphic one that, I fear, matches that of many Americans today:

…we are told that both the back-swimmer and the waterboatman grow, as do other insects of their order, by successive molts or changes of skin. They reach maturity, if they escape their enemies, and spend the winter at the bottom, as did their parents.

After enthusiastically describing these business-like little creatures to a neighbor one day, even persuading her to go with me and watch them in Meadow Brook, I was chilled and fairly disgusted at her question: “What are they good for?”

How could I answer her? Of the added joy of existence which they had given to me, I hadn’t the heart to speak. Her question told me that no such “foolishness” would appeal to her. Neither could I make her understand that, so far as I was concerned, no utility need be assigned to any creature as an excuse for its presence among us. As well ask: “What use, to them, are we?” But I saw she expected me to speak up in defense of these denizens of Meadow Brook, and so I said: “Oh, food for fish!”—a lame response and totally unfounded on personal observation. A conciliatory “Umph!” assured me that my reply was entirely satisfactory, as there could be no question in any one’s mind as to the use of fish.

…that intelligent grown people should demand a reason for the existence of every other creature is nearly unforgivable. May the time soon come when the silly superstitions about animals and plants will cease to be visited upon the third and fourth generation, and supplanted by personal knowledge of nature. Man will become more tolerant of other creatures and less sure, perhaps, of his own exalted position in the universe. Let us hope that he will then see himself as others see him and begin to learn to love his neighbor as himself.

A hearty “Amen” to that, Mary! I also found myself nodding in agreement at the high value she placed on ferns — much in keeping with the Victorian fascination for them: “Who ever had enough of ferns? They are always the right thing in the right place.” I will close my account of The Brook Book with this charming passage extolling the joys of a winter nature walk:

I shall never again allow myself to be mewed up between walls of brick and mortar for any length of time. The arching tree-tops are temples which call to worship. Their voices and the murmur of the ice-rimmed stream mingle like soft music from a far-off organ. I will go often, and be lifted out of the humdrum of every-day existence. The outdoor world is full of life in winter. To know this life one needs only to be open-eyed and open-hearted; the spirit of winter is ever ready to guide, to cheer and to bless.

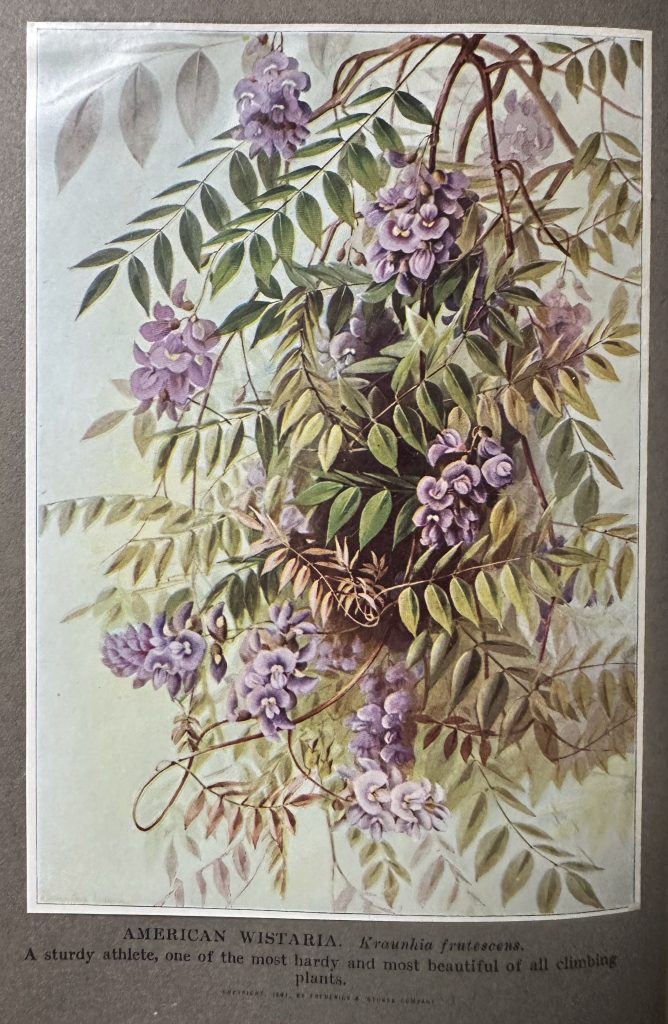

Among Green Trees offered quite a contrast. Julia explained that she had crafted an “all-around tree book” offering no less than four different points of view: the Nature-study side; the physiological side; the practical side; and the systematic side”. Ellen herself clearly favored the nature-study side, and I would have to concur. The portions of the book covering the wonders of buds, branches, and bark were by far the most fascinating. Indeed, once the book transitioned into chapters on planting and caring for trees (including when and how to spray them with various toxic chemicals) I lost interest. I considered reading the detailed accounts of different trees (systematic side), but opted to be satisfied with having read on the the first half of the book (though, given the oversized pages and modest font, that was still considerable text).

Although Julia comes across as a bit more sophisticated and professional in tone, she comes alive when speaking about her true passion, Nature-study. “Nature-study,” she announces, “is a keen, appreciative study of the common things around us. It means accurate seeing and clear thinking. Nature-study is the most vital idea today in education. It is studying things instead of studying about things. Under it, the commonplace becomes transfigured.” It is intriguing to note that her choice of “transfigured” echoes the religious tone of her sister’s description of tree-tops as “temples which call to worship.” There is a spiritual, transformational facet to Nature-study, one that is largely neglected (or outright avoided) in environmental education programs nowadays.

Lest we get too serious, Julie also reminds her readers of the joy that can be found learning from nature. In a chapter on how leaves are arranged on branches, she observes that “Leaf-arrangement is intensely interesting, when we come to study it. The botanists try to scare the common folks away by calling it Phyllobotany. But they can’t keep the fun all to themselves. Let us get into their pleasant game.“

IJulia clearly loved trees, and went out of her way to describe them as akin to human beings. Indeed, the subtitle of her book is “A Guide to Pleasant and Profitable Acquaintance with Familar Trees“. Early on in the work, she observes that “Trees speak a language, if only we have the patience to learn it. It’s a sign language, and through it they tell us all manner of interesting things about how they make their living — about their hopes and their disappointments.” A bit later in the book, in a chapter called The Sleep of Trees, she declares that “Trees are, after all, very much like folks! …In winter, trees put on their warmest coats — a fashion set by the woodchuck and the bear — and just sleep and wait for spring! In warm weather a tree goes to sleep at sundown, and wakes up in the morning. If the sky is overcast, the tree is drowsy; if rain sets in, it goes right off to sleep.” One reviewer felt compelled to remark on the “many unscientific and misleading statements” in the book, particularly her lines about trees sleeping: “We suppose that this is a reference to the photosynthetic process, but to the uninitiated this would convey the idea that the tree is actually drowsy in the same sense that animals are.” Ironically, recent research on plants has revealed that they “behave” in particular ways and even have an innate, though highly distributed, “intelligence”.

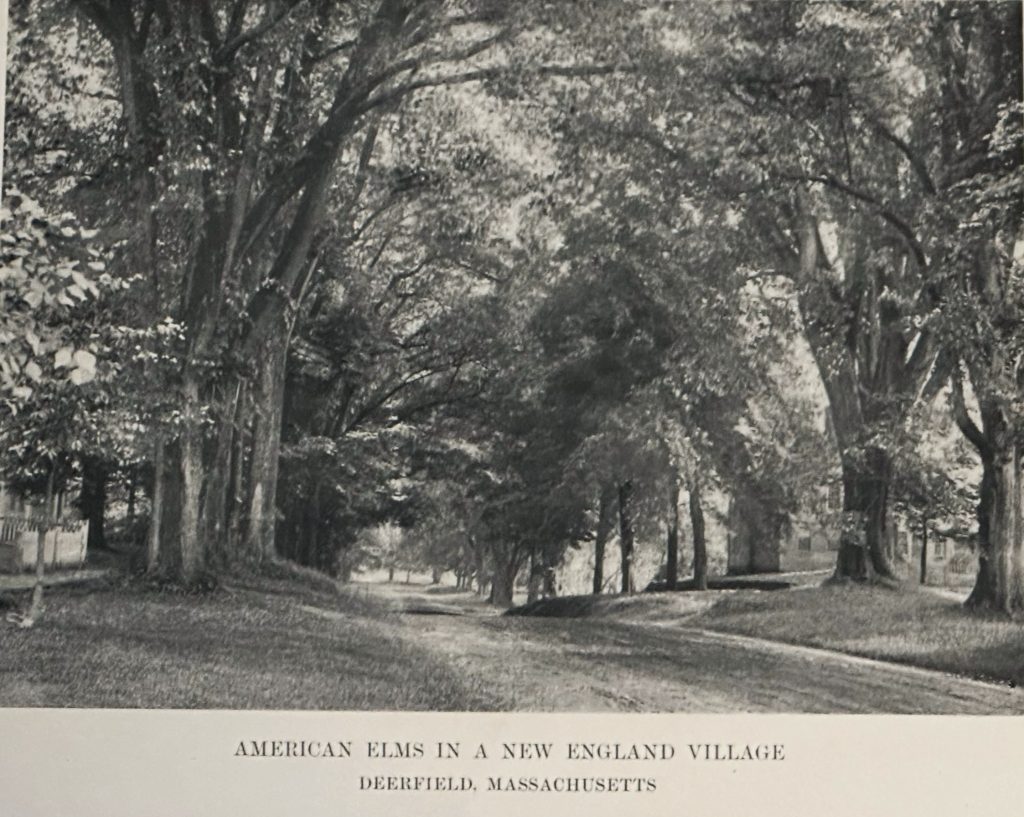

Reading books that are 100 years old or more, I sometimes find myself a bit jarred by having passed into a long-gone world. In the case of Among Green Trees, this experience took the form of images and passages concerning elm trees. Thanks to the ravages of Dutch elm disease, it has been more than 50 years now since any elms could be found in backyards and along city streets. Julia opens her book with a lengthy quote from an 1841 article by Nathaniel Peabody Rogers (her abolitionist grandfather), part of which celebrates the elm:

And the elm — the patriarch of the family of shade, the majestic, the umbrageous, the antlered elm! We remember one at this moment — in sight from our own home on the banks of the Pemigewassett. It stood just across that cold stream, by the roadside, on the margin of the wide intervale. It stood upon the ground as lightly as though “it rose in dance,” its full top bending over toward the ground on every side with the dignity of the forest tree, and all the grace of the weeping willow. You could gaze upon it for hours. It was the beautify handy-work and architecture of God, on which the eye of man never tires, but always looks with refreshing and delight.

Julia herself extolled the glories of a New England village lined with elms:

Especially impressive to me was the little village whose main street forms the frontispiece of this volume. It is hardly what you would eall a populous village. There is just this one long avenue, with a few little feints at cross streets; no railroad, no factory, no noise, no bustle—just the quiet industries of a village whose commerce is with the thrifty farmer folk round about. It is not a village you could duplicate in the west, for the houses are century old, solidly built, and mostly innocent of paint. There are lilacs, purple and white, leaning up against the houses, and quaint, old-fashioned gardens shut in behind low picket fences.

The glory of the old place is its double row of superb American elms, which arch above the long street, intermingling their tops, and making of it a shadowy aisle with vaulted arches, like some vast cathedral. Long ago the villagers dug little trees im the neighboring woods and lined the road on both sides with them. Then they let them alone! Violets and ferns came with them from the woods, and spread undisturbed in their new environment. To-day they may still be seen among the gnarled roots of the patriarchal trees, springing out here and there as they have been doing for a hundred years.

Alas, the elms are long gone now, relics of another age.

My next book,

My next book,