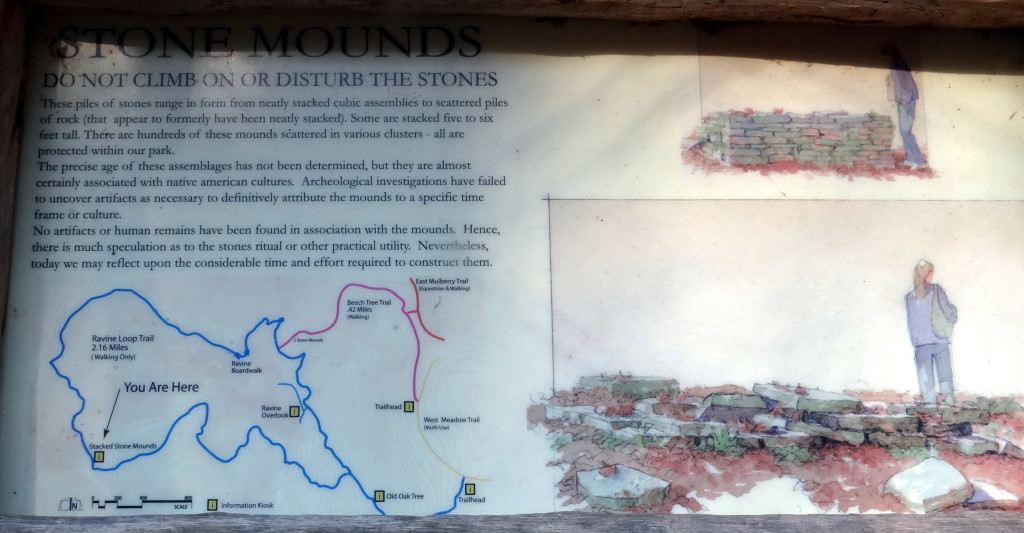

As a resident of Chattahoochee Hills now for nearly five years, the author has grown to appreciate more and more all of the open space that has been preserved as parkland in our community. While he still takes long day trips in search of new trails to hike or wildflowers to photograph, he also enjoys the pleasure of being able to drive only a few minutes from home and set out onto the trail. One such place he has come to treasure is Hutcheson Ferry Park, a 103-acre park on Hutcheson Ferry Rd near the intersection with Hearn Rd. in Chattahoochee Hills. The park will officially open to the public in a ceremony on Saturday, June 18th, 2011.

At a glance, the park seems unimpressive, more of a venue for a concert or fair than a stunning natural area. Much of the main entrance area of the park is mowed, with isolated trees scattered in the lawn. But go off the beaten path a bit — over a berm or beyond a fence, and wonders await.

The park includes a rock outcrop habitat with mosses, lichens, and aged eastern red cedars. It also has an extensive swathe of former pastureland that has an open, almost prairie-like feel to it. While Cochran Mill Park, a larger park with woods and streams a few miles away, has a few outcrop areas of its own, they do not quite achieve the species variety and beauty of the one at Hutcheson Ferry Park. And the hillside meadows of Hutcheson Ferry Park are not like any other spot this author has seen in other parks in the region.

The first treasure lies just over the hill, literally. From the open entrance area, set off across the grass (avoiding the fire ant nests) headed east, go up a short slope, and find a path through the tangled growth to a space where the land opens out, and the ground is nearly bare rock, with a layer of lichens and mosses. If you are particularly fortunate, you will arrive after a rain, when the rock moss that is usually dry and purplish-black has turned emerald green, and the resurrection fern growing on the side of an old red cedar is brilliant green and thriving rather than appearing brown and dead.

For most of the year, tough, the rock outcrop environment is a harsh place. During the summer, daytime air temperatures just above the granite surface can climb to 120 degrees or more, and the only water is a memory of a thunderstorm many weeks previous. Without soil, the thirsty lichens and mosses take what water they can after a rain, make food and grow for a short time, then go dormant again, waiting for another storm.

Life has specialized to survive under such conditions. Take lichens, for example. They are an odd partnership of a fungus and an alga. Algae usually live in water, but the fungi provide them with “space suits” so that they can dry out and still survive. Fungi, on the other hand, usually have to live on rotting vegetation in order to make their food. But as part of the lichen partnership, they have “taken up farming” by recruiting algae to make food for them. Fungi are one of the few life forms able to occupy bare granite. Another plant well-adapted to almost no soil or water is the prickly pear cactus, which can be found scattered about the outcrop.

Although the plants may be tough in the face of climatic extremes, the granite rock outcrops here in Georgia are actually very fragile places. Too many feet tramping across the outcrop can kill lichens and mosses, leaving scars that won’t fully heal for decades. Historically, granite outcrops were treated like waste places; often rubbish would be dumped or even burned on them. Fortunately, the outcrop at Hutcheson Ferry has been left alone for the most part, although one area was quarried many years ago. After the park opens, will we all be able to visit and appreciate this marvelous spot without harming it?

To get to the meadows at the park, your path leads back down the hillside and south along the mowed roadway. Soon, you arrive at a newly constructed fence, evidently planned to keep visitors far away from Palmetto Reservoir until reservoir access arrangements can be made with the City of Palmetto. Until then, the open landscapes will be off limits. Or they will be, that is, once a gate is constructed and a sign put up. Meanwhile….

Beyond the fence, the path leads briefly upward onto a hilltop, and then down the other side, eventually arriving at a stand of pines and sweet gums and, beyond that, the reservoir. The lake water is lovely, but I find greater appreciation in the open space between. On sunny days, you are liable to find dragonflies, damselflies, and grasshoppers on your walk. The various grasses mostly grow in only a thin mantle of soil. In one spot, the rock beneath is exposed at the surface over an area of several feet. This may be why the forest has been taking so long to reclaim areas that are no longer mowed, or mowed only very infrequently. So far, persimmons have been almost the only tree species to occupy former pasture ground. There is also a stand of mature red oaks beside the path, about halfway between the fence and the reservoir. Beneath the oaks is a ground cover of periwinkle, a non-native plant with dark-green, oval leaves and purple flowers that would have been planted there by someone. Although this writer has not been able to find evidence of a building foundation, he is convinced that the oak grove was once the site of someone’s house. It would have been a lovely place to call home.

This article was originally published on June 3, 2011. Since that time, the path beyond the fence has no longer been maintained.