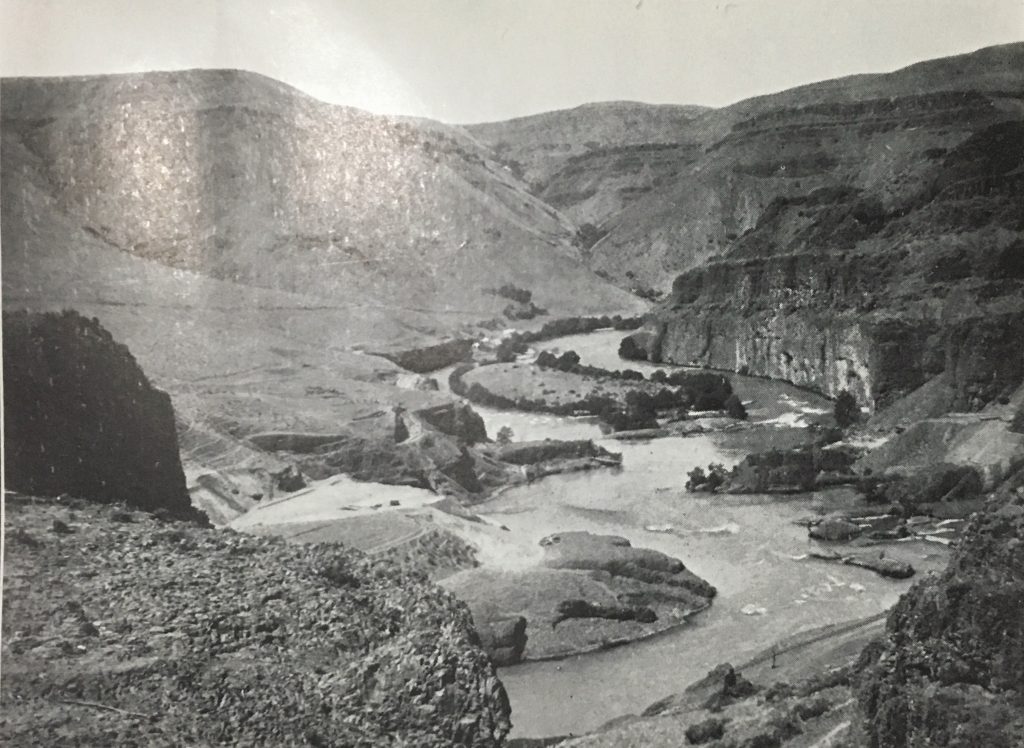

My Berkshire house sits at the head of an ancient orchard and looks, on one side, up a steep, high, densely wooded mountain shoulder; on the other, over rolling fields plumed with maples and sentineled with little cedears, to the pines on a hill and the wall of tamaracks edging the great swamp. Trees are my cloud of witnesses. Ever they surround me, and from the once contemptibly familiar they have become, to eyes grown wiser in seeking beauty and solace in the familiar, a constant source of charm and wonder and delight…

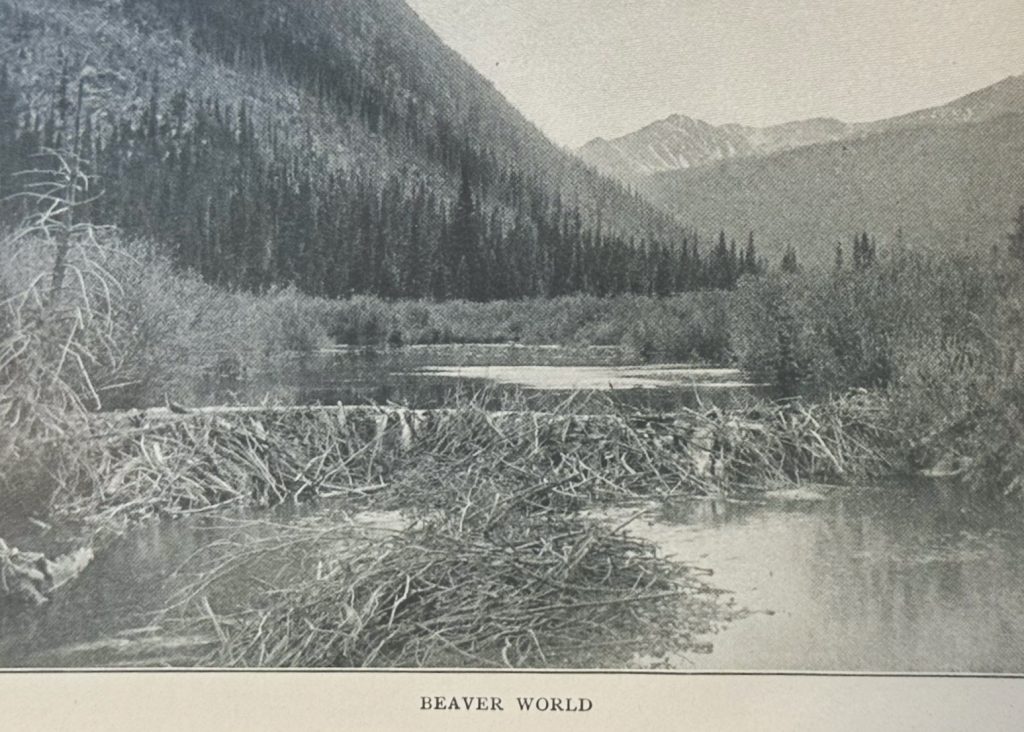

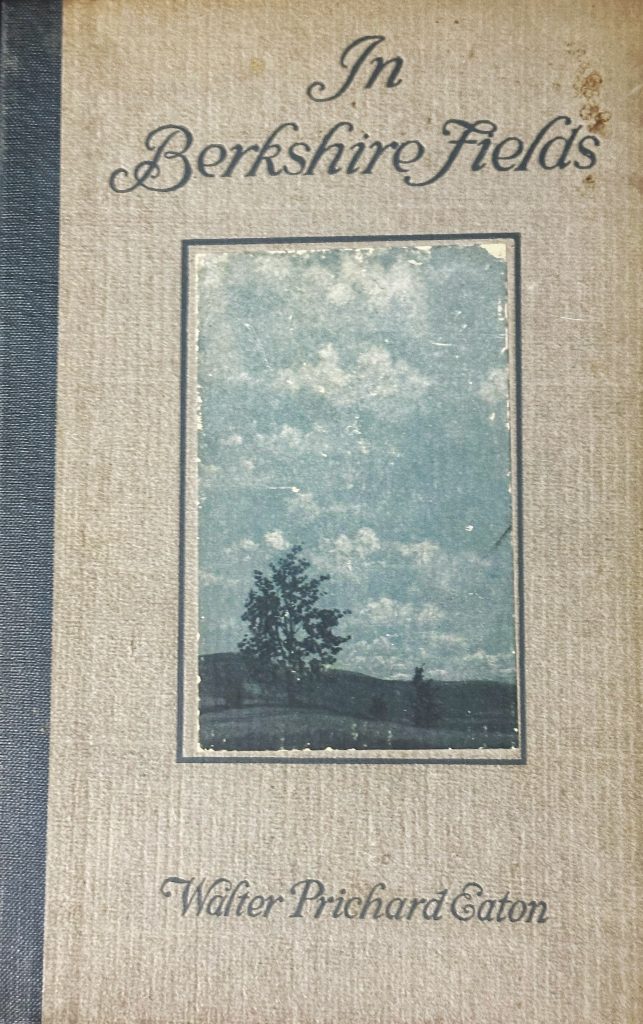

Last night, I finished the last few essays in In Berkshire Fields (1920) by Walter Prichard Eaton (1878-1957), and closing the book was a bittersweet moment. It was my last book by Eaton, and this post is my farewell to an author I have grown to know as a companion and friend. As an author, his prose is generally more effective than soaring, and more informative than inspirational. While I finish some books with pages of notes of favorite passages to share, that generally does not happen with Eaton’s writing. Eaton was by no means a scientist of nature; rather, he was a fairly wealthy theater critic with a penchant for wandering the woods and fields around his Berkshire home, punctuated by occasional camping and hiking treks to the West. After living for several years in a home on just five acres in a western Massachusetts town, he purchased 200 acres on the slopes of Mt. Everett (the second most prominent peak in Massachusetts, after Greylock, although only the eighth tallest). Wandering his property, he would occasionally encounter hired help, pruning a tree in his orchard. Writing during the Depression, he observed that he had several friends who had gone golfing in Bermuda for the winter, and half-wished he could join them — indicating, in passing, that the cost did not hold him back. He was a golf aficionado, in fact — he mentions a local golf course or aspects of the game a few times in his writing. Despite these things, I find his writing sincere and his sense of place in the Berkshire hills sufficiently robust that I feel transported there with him as I read his work. His inspiration was chiefly Henry David Thoreau, though he dedicated In Berkshire Fields to William Hamilton Gibson. He did not advance the cause of science with discoveries or insights, although his essay on why we shouldn’t rake leaves (more anon) at least shows that the idea dates back at least to pre-1933. His writing is pleasant, and I am grateful to have shared his world over five volumes. In particular, I find him noteworthy because his nature essays are the first that I have read that refer to World War I and the Great Depression. Indeed, his 1930 and 1933 titles are practically the only ones I have found by nature authors published in those years.

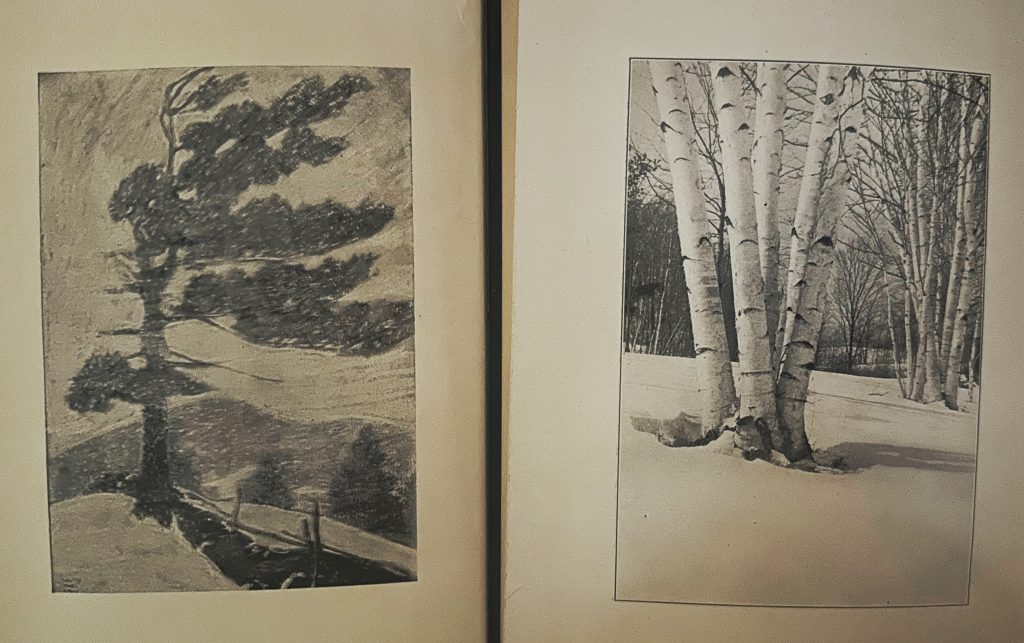

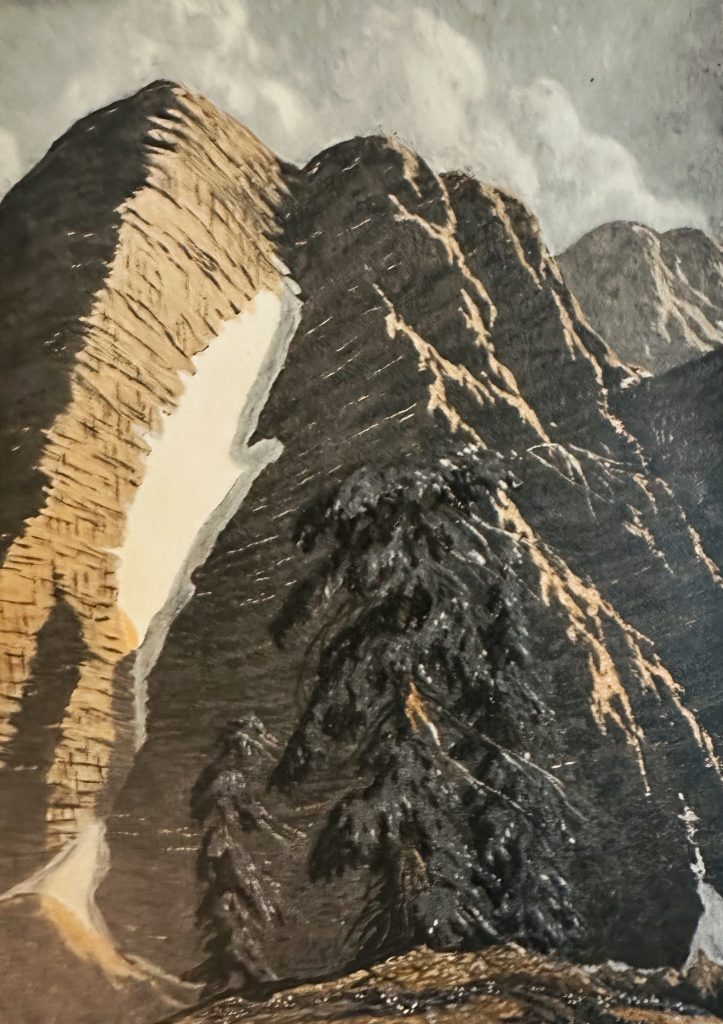

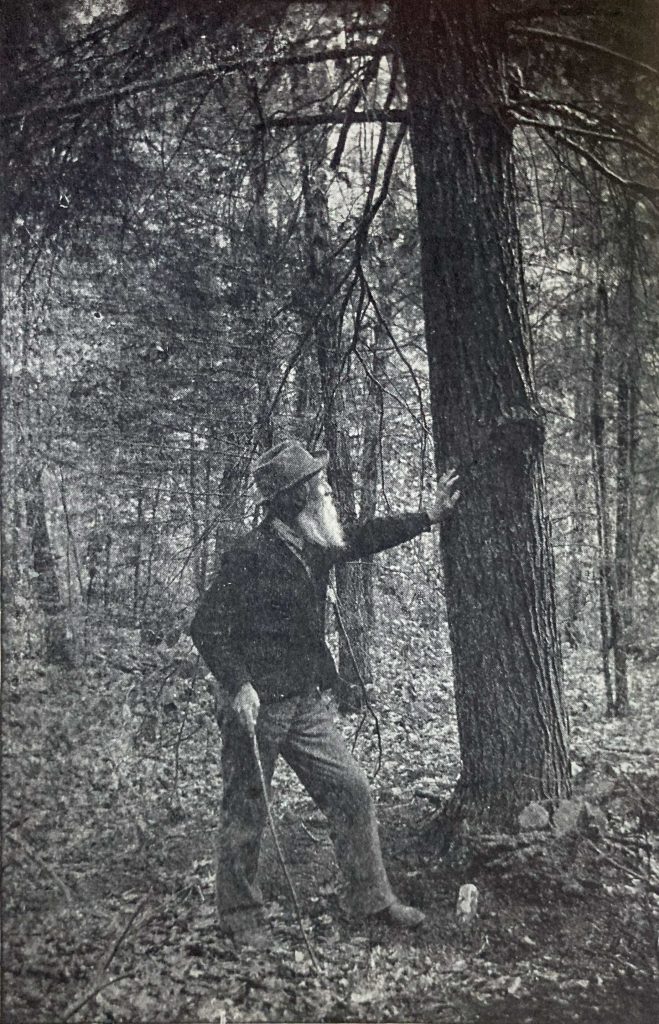

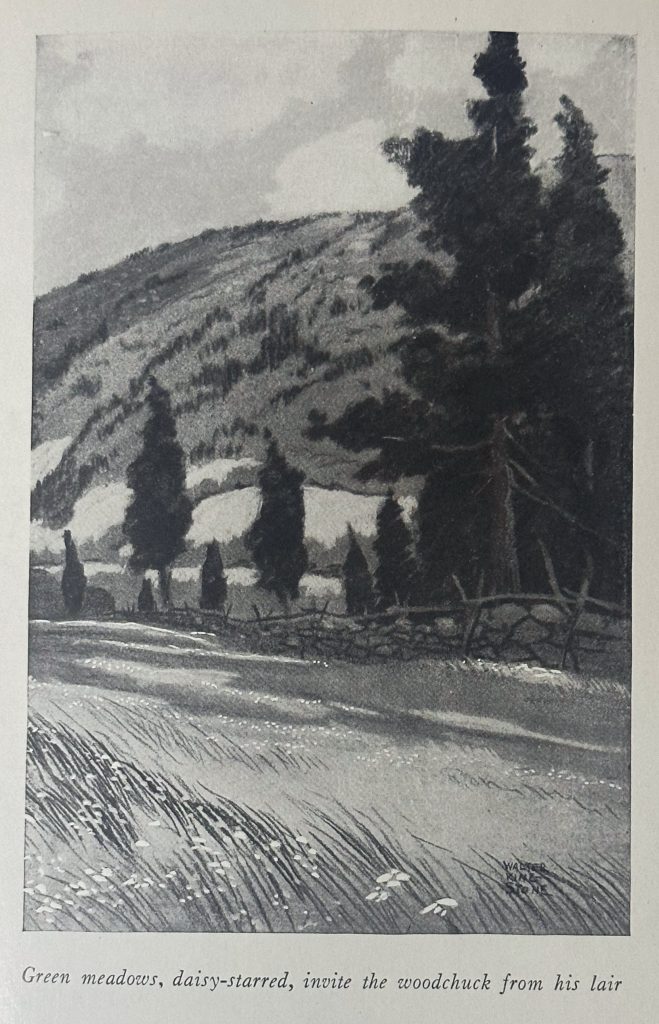

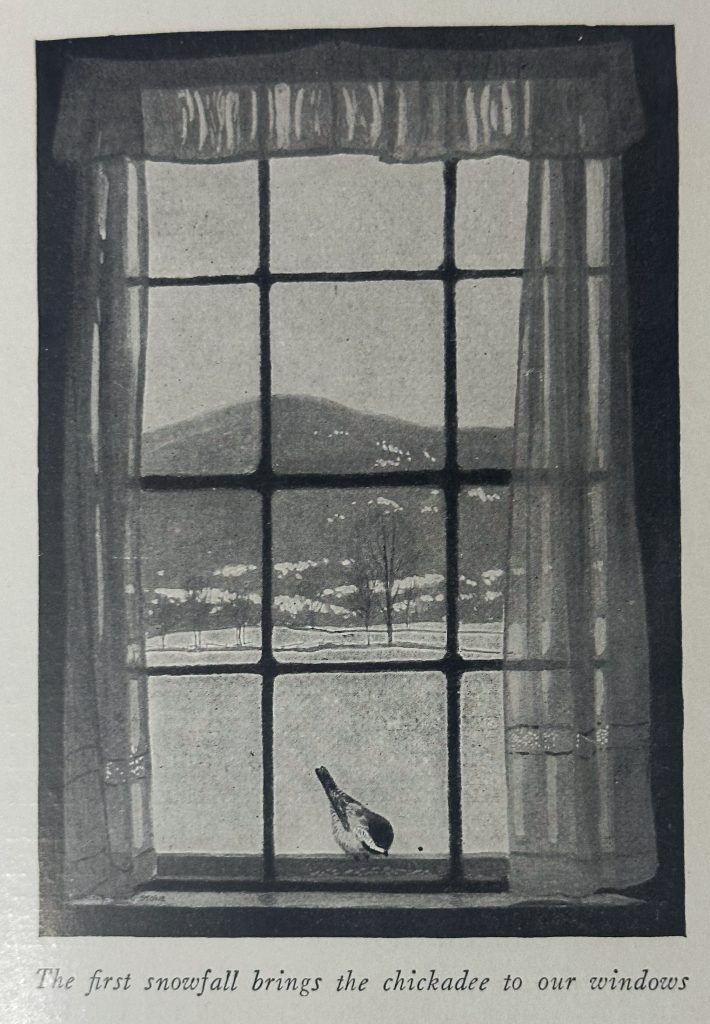

First, though, a few words about Eaton’s substantial work, In Berkshire Fields. By substantial, I mean that it weighs 2 1/2 pounds, although it is just over 300 pages. The paper is exceedingly thick, and the illustrations are numerous. The artist, Walter King Stone (1875-1949), makes multiple appearances in Eaton’s essays, including sharing tales of his own animal encounters. A gifted illustrator and Cornell University art professor, Stone provided artwork for many publications and collaborated with Eaton both here and in Eaton’s Skyline Camps. Based on his excellent images in this volume, Stone also had a predilection for chickadees.

In Berkshire Fields is a deep investigation of nature in the Berkshires at the time — a region transitioning from agriculture back to woodland. Although no evident attempt was made to unify the work, the essay collection covers a range of natural history topics, from birds (obviously a favorite subject of Eaton’s) to mammals to trees and orchids to the landscape as a whole. Mostly, the essays themselves are workmanlike, making their way through aspects of a chosen topic (a particular bird species or group of birds, foxes and their kin, etc.). They become most engaging when given over to brief narratives, such as tales about the behaviors exhibited by various semi-tamed crows. (Evidently, it was a rural pastime in 1920 to capture a juvenile crow and rear it in the home for amusement.) One essay that stands out is “From a Berkshire Cabin: An Essay in War-Time”. Writing from a small cabin high on the slopes of Mount Everett, Eaton grapples with the paradox of being surrounded by nature’s calm beauty while a war was raging in Europe:

I am aware with a pang of almost intolerable sorrow of the peacefulness about me. How strange, how bitter the very word sounds! Even here, where I have come to forget for a day, I cannot forget. Dear friends, youngsters I have watched grow up, relatives, a myriad unknown brothers of every creed and color, are to-day plunged in bloody battle killing and being killed, and man has made of peace a mockery… What I try to realize right now with a care never before exercised in what was essentially a care-free enjoyment what it is exactly in my surroundings that gives me so much pleasure, and from that to realize, if possible, what strange duality in our natures must be explained in order to understand even a little the terrible facts of armed conflict.

Ultimately, Eaton realizes the extent to which he, and all humanity, are complicit in the world war. In a passage eerily appropriate today, Eaton recognizes the selfishness that comes from taking individual rights for granted without recognizing that democracy requires the dedicated participation of everyone:

We must descend from our mountain cabins, from our towers of ivory; we must come out of our gardens and up from our slums, forgetting our beautiful enjoyments, or our precarious jobs which carry no attendant enjoyments, and remembering only the ideal of beauty in our hearts, the ideal of beauty which means, too, the ideal of justice and mercy and peace and happiness for each and all, demand of what rulers we shall find that they give over to us the machinery which controls our destinies, and the destinies of all our fellows. The world to-day is fighting for democracy. I see my crime to have been that I considered democracy a condition wherein I was let alone, not wherein I was an active participant three hundred and sixty-five days in the year, fighting to write my best personal ideals into the whole. That, I believe, has been the crime of the entire world, and in this sense it was not the Kaiser who made the war, but Goethe and Schumann and Beethoven. It was not “‘secret diplomacy,” trade jealousy, and all the rest, that kept the nations apart, straining at one another’s throats; it was the selfish complaisance of all the people who had the love of right and beauty in their hearts—and locked it there for their private enjoyment. The fight for democracy is only just beginning, for only now are we beginning to comprehend what democracy means, to glimpse the depths of its sacrifices, the glory of its creative spirit, the beauty of opportunity that it may be made to hold for common men. Had I the eloquence, I would write a new manifesto, and its slogan would not be, ‘‘ Workers of the world, unite!’ but, ‘‘Lovers of beauty in the world, unite! and capture the machinery by which we have been ruled in ugliness and cruelty.”” There would be no need of a union of the workers, then, for we should all be workers for the common weal. …

Making his way back down the mountain slope to home, Eaton loses much of his fervor, observing that “It is hard to come down from a mountain cabin, from an ivory tower, to give up a solitary possession or resign a comfortable privilege! If I owned a factory would I consent without a bitter struggle to industrial democracy? I ask myself as I pass the foxglove plant and touch its trumpet with my fingers. No—probably not. Undoubtedly not, I decide as I reach the clearing. Having determined what would be necessary to prevent future wars, Eaton realizes with bitter honesty just how difficult such a path would be. I am at once smitten with his integrity and disappointed with his lack of commitment. It is as if he glimpsed the entrance gate to Utopia, only to turn away.

Throughout the book, Eaton evidences appreciation for most wildlife, and particularly songbirds. However, in keeping with the time, he tends to emphasize the benefits of animals for humans, rather than advocating that other living beings ought to be protected for their own sake. Porcupines, for instance, “appear to serve no useful purpose”, while certain hawk species are “cruel” because they hunt farmers’ chickens. Ultimately, though, Eaton recognizes that calling for the outright extinction of certain species would likely be most unwise:

“…we are slowly learning that the balance of nature is something which should not be too rudely disturbed without careful investigation. We have learned the lesson—a costly one— with regard to our slaughtered forests and shrunken water-powers. We are learning it with regard to our birds. And it is certainly not beyond the range of possibility that the varmints—the flesh-eating animals like foxes, weasels, ’coons, and skunks—perform their useful functions, too, in their ceaseless preying upon rodents, rabbits, and the like, more ‘ than atoning for their occasional predatory visits to the chicken-roost. At any rate, who that loves the woods and streams does not love them the more when the patient wait or the silent approach is rewarded by the sight of some wild inhabitant about his secret business, or when the telltale snows of winter reveal the story of last night’s hunt, or when the still, cold air of the winter evenings is startled by the cry of a fox, as he sits, perhaps, on a knoll above the dry weed-tops in the field and bays the moon? To me, at least, the woods untenanted by their natural inhabitants are as melancholy as a deserted village, an abandoned farm, and I would readily sacrifice twenty chickens a year to know that I maintained thereby a family of foxes under my wall, living their sly, shrewd life in frisky happiness, against all the odds of man.

While the 1920 volume is rich with splendid artwork and lavish with thick paper and a decorated cover, the other two volumes of Eaton that I recently read are far more plain in appearance. The paper is browned and of much poorer quality, and the covers are undecorated apart from labels identifying the title and the author (albeit embossed in gold). There are no illustrations apart from a lovely pair of frontispieces by Walter King Stone and photographer Edwin Hale Lincoln, respectively (see below), and the books are about 130 pages each. New England Vista dates to 1930, and On Yankee Hilltops to 1933. Both works contain more essays about the landscape of the Berkshire hills and its wildlife, along with rambles in search of the cellar holes of long-abandoned settlers’ homes and reflections on home gardening. Published in the early days of the Great Depression, New England Vista is most noteworthy for its essay about leaf raking. “Burning Wealth” argues that fallen leaves ought either to be left where they lie or else gathered for composting and reuse. “Every leaf that falls represents nourishment taken out of the ground,” Eaton patiently explains to the reader. “Left to rot, it puts this nourishment back into the soil. Burned up, the nourishment is forever lost, and if it is not supplied artificially, the soil is gradually impoverished and dried up. Every pile of leaves that is composted is rescued wealth. Every pile of leaves burned up is wealth destroyed.” I suspect this recommendation aligned well with the concerns of thrifty readers struggling to keep afloat financially in the aftermath of Black Tuesday.

Speaking of Black Tuesday, the Depression itself (with a small “d”, though) puts in an appearance in On Yankee Hilltops. In “Sweets for Squirrels”, he mentions how “Two of my friends, appararently unaffected by the depression, are in Bermuda playing golf.” While working on building a new garden path along a limestone ledge, Eaton observes how his mind keeps trying to argue that he is better off for not having joined them (a decision that does not appear to reflect any financial hardship on his own account). Ultimately, Eaton concludes that “…I was better employed than if I had been playing golf.” Fortunately, he does not end his musing there. He shares about a visit from a struggling poet, living “up in the hills” in a shack on a small strip of ground, who walked ten miles just to call on Eaton.

When he sits in my study, and we talk of night sounds, and winter colors, and the long tramps the pheasants take, or discuss poetry, I am always a little ashamed of the litter of possessions which surround me–books, prints, tobacco jars, Dresden figures, overstuffed chairs, telephones, golf clubs, mirrors, goodness knows what all, accumulated to minister to the supposed needs of one unimportant human being who can hardly be considered an individual unless he can stand alone, free of such truck, and find his happiness in the creative power of his spirit, or, at the very least, of his own two hands.

Eaton then lists some of the “material comforts” of the Industrial Revolution and the Gilded Age — motorcars, radios, tiled bathrooms, macadam highways, and the like. “We organized ourselves into a vast society to produce them, entirely based for its stability on our desire and ability to consume them. Then something went wrong.” After the stock market crashed, people lost the ability to pay for all these things. Once there is an economic upturn, though, Eaton predicts that the seemingly endless whirl of production and consumption will automatically resume. Under those conditions, most people work hard, but to no avail — living empty lives creating nothing truly meaningful. The better path, he suggests, would be to find contentment with simple things:

To rediscover the world of simplicities, the joys of creating with one’s own hands, the profound satisfactions of expressing an inner sense of beauty through the manipulation of visible forms,–trees, plants, paints, notes of music, or what not,–the relief of a slackened quest for Things, is to rediscover, perhaps, one’s self.

If only we could, collectively, make a better choice. Again, Eaton maps out the way for humanity to follow, only to stumble against the realities of the human condition. “I’m not overly hopeful,” he confesses.